Tuesday, December 16, 2025

Nuclear “Time Bomb” On India-China Border! Garage Files Revive CIA’s Cold War Secret That Could Trigger Hell

By Sumit Ahlawat

-December 16, 2025

Some stories refuse to die. In 2014, EurAsian Times reported on how the U.S. lost a Nuclear device in the Himalayas that was designed to snoop on China.

The story involved a Plutonium nuclear device lost at the roof of the world, which can be turned into a dirty atomic bomb, can leak radioactive material and poison the Ganges, India’s holy river that feeds millions of people, and can cause landslides, avalanches, and flash floods, it’s easy to understand why the story will not die its natural death, even after more than 60 years have passed.

A Plutonium-based nuclear device, after all, can last for centuries.

By now, the broad contours of the story are familiar.

In the haughty days of the Cold War, the CIA was losing sleep after Maoist China conducted a nuclear test in 1964. Caught off guard and determined to keep a tab on Beijing’s future nuclear and missile technology, the CIA came up with a bold plan.

To place a nuclear-powered snooping device on one of the Himalayas’ tallest peaks. There, sitting at over 25,000 feet and buried in many feet of snow, the device will quietly eavesdrop hundreds of miles into Tibet.

The CIA, however, could execute only half the plan. The nuclear-powered device was indeed sitting in the Himalayas, buried somewhere in the snowy peaks of Nanda Devi, but it was not placed there; the CIA lost it.

It was last seen in 1965. Since then, it’s not eavesdropping on China; instead, it is hanging like a ticking nuclear disaster in the Himalayas that could poison the water supply of millions, leak radioactive substances in the glaciers, or trigger landslides, avalanches, and flash-floods in an ecologically sensitive area.

The story first broke in 1978; since then, despite the best efforts of the US and Indian governments to bury the matter under the icy Himalayan sheets, it refuses to die and keeps raising its ugly head every few years.

The story resurfaced in 2021 when flash floods near Nanda Devi killed over 200, triggering fears that the nuclear device could have caused the glacier to burst.

Last week, it resurfaced again after a trove of files was discovered in a Montana garage, showing how a celebrated National Geographic photographer built an elaborate cover story for the CIA covert operation — and how the plans completely unraveled on the mountain.

Ironically, the celebrated National Geographic photographer Barry Bishop was also the source of the first leak in 1978, and now, nearly 50 years later, his newly discovered garage files show that he has told only half the story.

Though just like in 1978, the story has not lost any urgency or sensation.

However, the story is more than its sensation. Above all, the story of how the CIA lost a nuclear device in the Himalayas in 1965 represents an epoch.

The age of the Cold War, when all bets were off, and all spooky games, no matter how outlandish, seemed fair game.

The story, in its own weird ways, also represents the last vestiges of the imperial age. A post-colonial world that is still in its nascent stage, and where millions of lives in the Global South can be gambled by a few hawkish spies in the First World, having a bloated sense of their own importance and a misplaced faith in the superiority of their mission.

A Celebrated National Geographic Photographer Aka CIA Operative

By 1965, Barry Bishop was not only a celebrated photographer but also a widely respected mountaineer. In 1963, he had conquered Mount Everest.

Bishop met Gen. Curtis LeMay, the head of the United States Air Force (USAF), at a cocktail party. During the party, Bishop told Gen. LeMay that from Mount Everest, he could see hundreds of miles inside Tibet.

Soon after, the CIA summoned Bishop and told him of a bold plan. Several US mountaineers and secret agents would slip into the Himalayas, carrying surveillance equipment in their backpacks, and place it on a mountaintop to intercept radio signals from Chinese missile tests.

According to The New York Times, “Records found in November in Mr. Bishop’s garage in Bozeman, Mont., show that National Geographic granted him a leave of absence to pursue the mission in the Himalayas.

“The meticulously kept files also chronicle his deepening involvement: studying explosives, receiving intelligence on China’s missile program and mapping out the summit assault. His files included bank statements, phony business cards, photographs, gear lists and menus, down to the chocolate, honey and bacon bars that the climbers would eat.”

However, the CIA had a problem. How to power the listening device in the Himalayas for many decades. NASA had a solution—a portable generator powered by highly radioactive plutonium.

Bishop recruited Mr. McCarthy, an experienced rock climber, for the mission.

Mr. McCarthy said the CIA offered him $1,000 a month and presented the mission as urgent for America’s national security.

The US then shared the plan with India, which had just lost a war to China in 1962, and was equally anxious about China’s nuclear program.

India’s Intelligence Bureau tapped Captain Kohli, a decorated naval officer who had just made history leading nine Indian climbers to Everest’s summit.

In interviews with Indian newspapers, Kohli later recalled being struck by the CIA’s arrogance. “It was nonsense,” Captain Kohli said.

The first plan that the CIA hatched, he recalled, was to put the telemetry station on Kanchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain after Everest and K2.

“I told them whoever is advising the C.I.A. is a stupid man,” Kohli said.

Mr. McCarthy shared the sentiment.

“I looked at that Kanchenjunga plan and said, ‘Are you out of your mind?'” he remembered.

“At that time, Kanchenjunga had only been climbed once,” Mr. McCarthy said. “I told them, ‘You’re never going to get all that equipment up there.'”

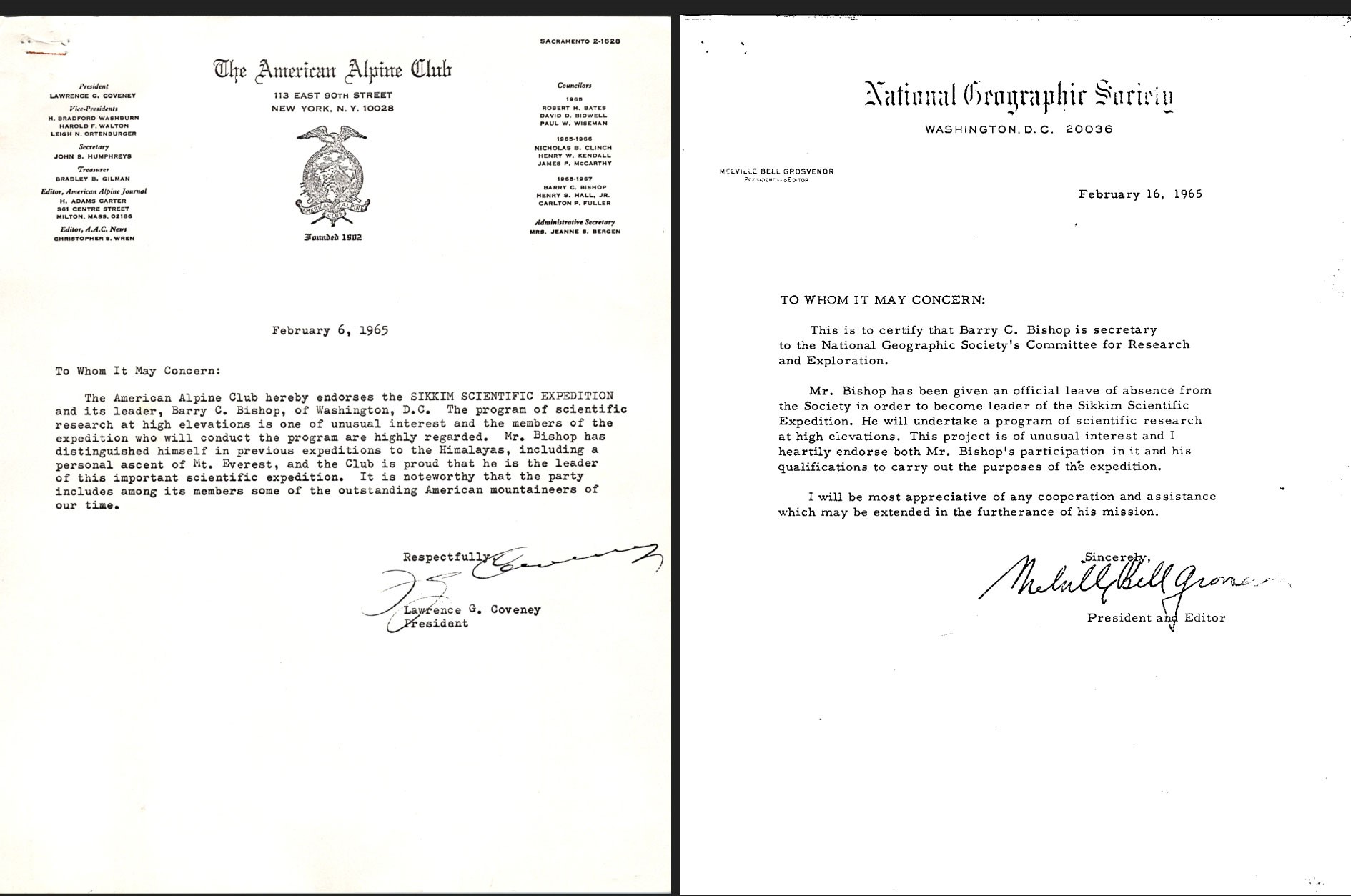

Bishop made business cards, letterhead, and a prospectus, all emblazoned with “Sikkim Scientific Expedition.” It was all a cover.

Letters of support for Mr. Bishop and his expedition from the American Alpine Club and National Geographic. Courtesy Barry Bishop Estate via The NYT.

Finally, and thankfully, Indians rejected the Kanchenjunga idea, saying it was in an “acutely sensitive” military area, according to Mr. Bishop’s files.

After much deliberation, the Indians and the CIA finally settled on Nanda Devi, at 25,645 feet.

However, Captain Kohli still had his reservations.

“I told them it would be, if not impossible, extremely difficult,” he said. Once again, he said, his concerns were dismissed.

The Indian and US climbers then met in Alaska for a quick practice run.

The Fateful Climb

In September 1965, the team began their climb of Nanda Devi Peak, carrying a portable nuclear-powered generator, listening antennas, and cables.

They had to move quickly because September is already the fag end of the climbing season in the Himalayas, winter and its ferocious storms were just around the corner, but they did not want to wait till next year.

However, the climbers were in the dark about what they were carrying.

Plutonium 238 sheds heat. Unaware of the risks associated with it, the Sherpas used it to warm themselves.

The porters jockeyed with one another to carry the plutonium capsules, Captain Kohli and Mr. McCarthy said.

“The Sherpas loved them,” Mr. McCarthy said. “They put them in their tents. They snuggled up next to them.”

Remembering this, Captain Kohli said, “The Sherpas called the device Guru Rinpoche (a Buddhist saint) because it was so warm.”

“At the time,” he said, “we had no idea about the danger.”

Finally, and thankfully, Indians rejected the Kanchenjunga idea, saying it was in an “acutely sensitive” military area, according to Mr. Bishop’s files.

After much deliberation, the Indians and the CIA finally settled on Nanda Devi, at 25,645 feet.

However, Captain Kohli still had his reservations.

“I told them it would be, if not impossible, extremely difficult,” he said. Once again, he said, his concerns were dismissed.

The Indian and US climbers then met in Alaska for a quick practice run.

The Fateful Climb

In September 1965, the team began their climb of Nanda Devi Peak, carrying a portable nuclear-powered generator, listening antennas, and cables.

They had to move quickly because September is already the fag end of the climbing season in the Himalayas, winter and its ferocious storms were just around the corner, but they did not want to wait till next year.

However, the climbers were in the dark about what they were carrying.

Plutonium 238 sheds heat. Unaware of the risks associated with it, the Sherpas used it to warm themselves.

The porters jockeyed with one another to carry the plutonium capsules, Captain Kohli and Mr. McCarthy said.

“The Sherpas loved them,” Mr. McCarthy said. “They put them in their tents. They snuggled up next to them.”

Remembering this, Captain Kohli said, “The Sherpas called the device Guru Rinpoche (a Buddhist saint) because it was so warm.”

“At the time,” he said, “we had no idea about the danger.”

99 Percent Dead

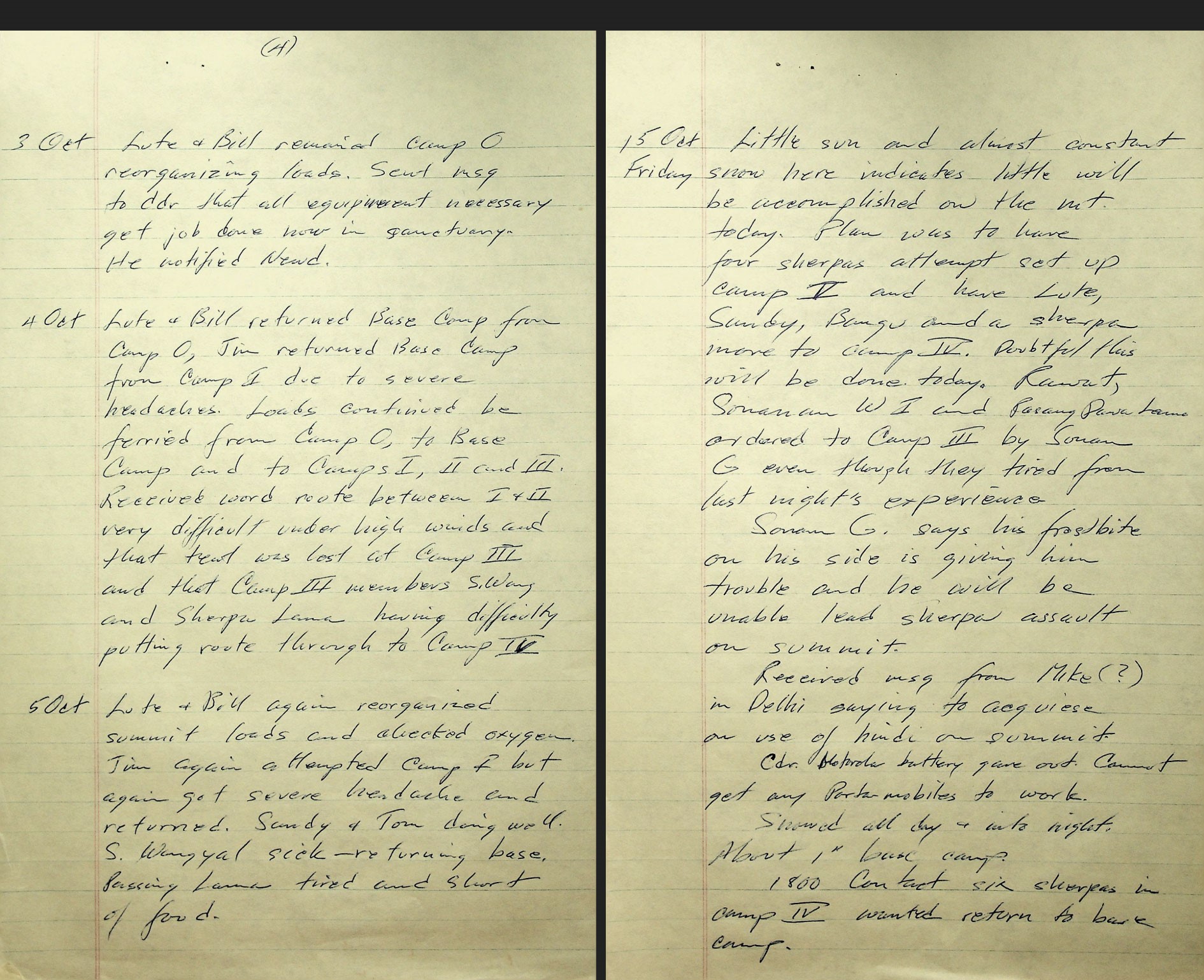

The NYT report quotes from Mr Bishop’s handwritten notes (discovered in the garage in November). The notes capture the hardships and the mission’s collapse.

Oct. 4: “High winds.” “Tent was lost.”

Oct. 5: “Short of food.”

Oct. 11: “Snows all day.”

Oct. 13: “Very discouraging evening.”

Oct. 14: “Jim tried again to move up but again developed a severe headache.”

Oct. 15: “Almost constant snow. Frostbite. Coming to a crux.”

Handwritten notes from Mr. Bishop’s files. Courtesy Barry Bishop Estate via The NYT.

Handwritten notes from Mr. Bishop’s files. Courtesy Barry Bishop Estate via The NYT.On October 16, a blizzard hit.

Sonam Wangyal, an Indian intelligence operative who was also an experienced mountain climber and, by all accounts, a very strong one, was huddled near the peak.

“We were 99 percent dead,” Mr. Wangyal remembered. “We had empty stomachs, no water, no food, and we were totally exhausted.”

“The snow was up to our thighs,” he said. “It was falling so hard, we couldn’t see the man next to us, or the ropes.”

At this time, Captain Kohli ordered his men to leave the device at a secure location and return.

“The Indian climbers pushed the boxes of equipment into a small ice cave at Camp Four. They tied everything down with metal stakes and nylon rope. Then they scurried down as fast as possible.”

The climbing season had ended. The team had to wait until next year to search for the nuclear-powered generator.

However, when the team returned the following year, they found nothing. The nuclear device has been lost at the roof of the world.

Captain Kohli recalls that had he known they were nuclear capsules, he would have asked the team to bring them back at any cost.

Subsequent expeditions were sent in 1966, 1967, and again in 1968, but the device seems to have been lost forever.

“The team used alpha counters to measure for radiation, telescopes to scan the snow, infrared sensors to pick up any heat, and mine sweepers to detect metal. They found nothing.”

Mr. McCarthy believes it “buried itself in the deepest part of the glacier.”

“That damn thing was very warm,” he said, explaining that it would melt the ice around it and keep sinking.

Perhaps the nuclear device is still there at the bottom of a glacier, melting the ice, which could trigger avalanches and flash floods, or it could leak radioactive substances into the glacier, poisoning the waters of the Ganges.

However, despite the debacle, the CIA kept pushing to set up a mountaintop station to spy on China.

In 1967, a team of climbers finally managed to install a new batch of surveillance equipment, powered by radioactive fuel, on a flat ice shelf on a lower summit, near Nanda Devi.

But the device, due to its heat, kept sinking.

“That sputtering telemetry station was shut down in 1968, with the equipment retrieved and sent back to the United States, according to Indian documents.”

According to Kohli, who wrote a book on the topic, “Spies in the Himalayas: Secret Missions and Perilous Climbs,” another such device was set up in the Himalayas in 1973.

However, by then, the US had made significant advances in spy satellite technology, rendering these rudimentary, high-risk nuclear-powered devices in the Himalayas redundant.

The Nanda Devi story first broke in 1978, and Mr. Bishop was one of its sources. However, he requested not to be named, fearing it would muddy his legacy as a celebrated National Geographic photographer.

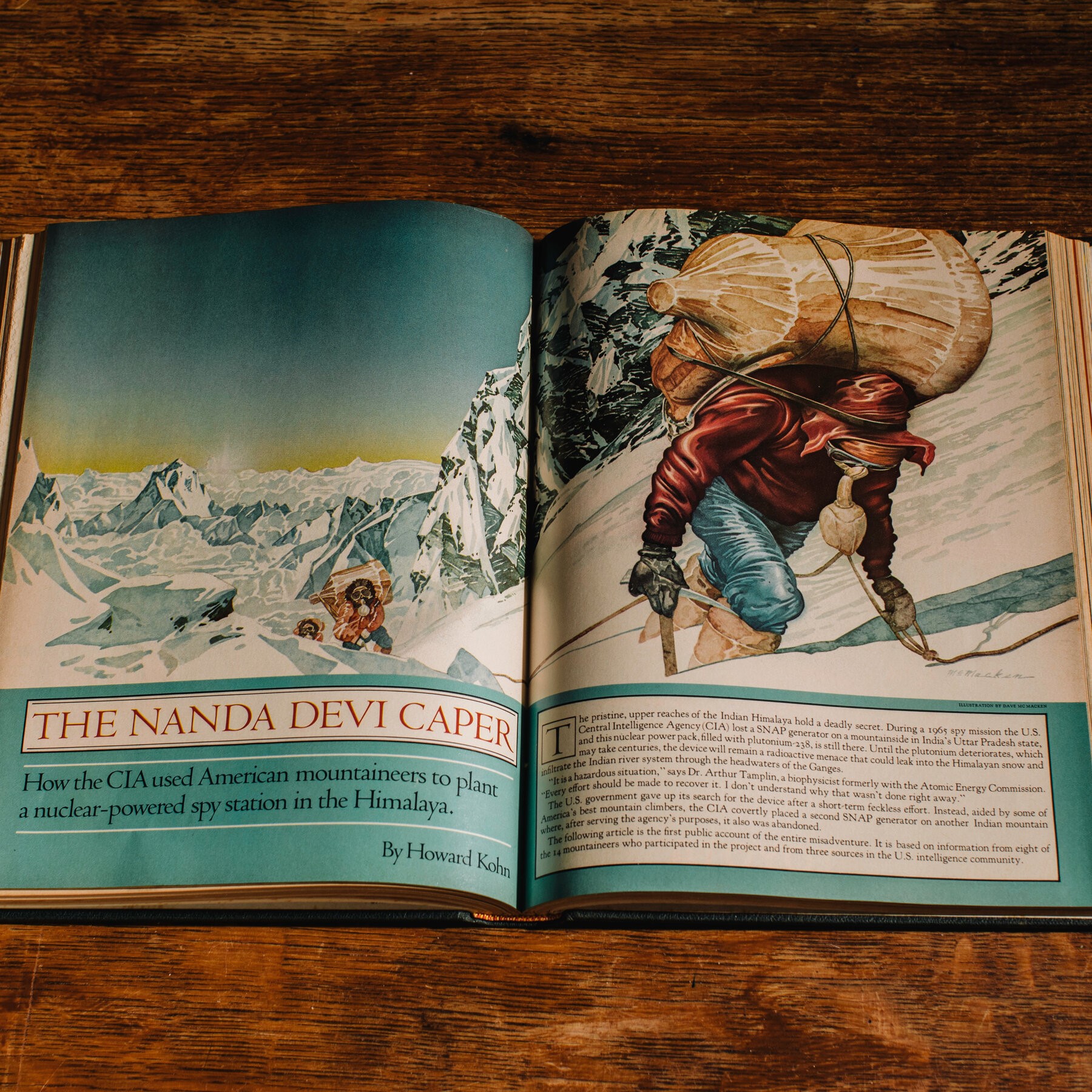

The Nanda Devi story was first published in Outside Magazine in 1978. Courtesy The NYT.

Incidentally, the US has also lost a pair of nuclear-powered generators off the Californian coast in 1968 when a weather satellite crashed.

“The government was so anxious to recover them that the Navy sent half a dozen ships and plumbed the ocean for nearly five months until they were found.”

Which raises the question, why was the US so lax about the lost nuclear device in the Himalayas?

Was it because it risked the lives of Indians and not the Americans?

“The government was so anxious to recover them that the Navy sent half a dozen ships and plumbed the ocean for nearly five months until they were found.”

Which raises the question, why was the US so lax about the lost nuclear device in the Himalayas?

Was it because it risked the lives of Indians and not the Americans?

Sumit Ahlawat has over a decade of experience in news media. He has worked with Press Trust of India, Times Now, Zee News, Economic Times, and Microsoft News. He holds a Master’s Degree in International Media and Modern History from the University of Sheffield, UK.

No comments:

Post a Comment