Zamri denies fleeing to Thailand, says willing to meet IGP

Published: Mar 14, 2026 3:20 PM

Updated: 6:29 PM

Controversial preacher Zamri Vinoth, who police previously said had fled to Thailand, has denied “running away”, insisting that he will personally meet Inspector-General of Police (IGP) Khalid Ismail if necessary.

In a Facebook post today, Zamri (above) also questioned why police were seeking to press charges against him for allegedly disturbing public peace and issuing seditious statements, asserting that he had committed no offence.

Instead, he claimed that several other figures, including DAP MP RSN Rayer, activist Arun Dorasamy, and Urimai interim deputy chairperson David Marshall, were the ones who have been “inciting” the public.

“Why would I run? I have said many times that if you want to catch me, also catch Rayer. If you want to charge me, charge them too!

“I will meet the IGP myself if there is a need to, InsyaAllah…I have not run away and there is no need for me to run away!” Zamri declared.

His Facebook page, which was initially accessible, now appears to have been restricted, with screenshots of his post now making the rounds on social media.

Malaysiakini has contacted the MCMC and Zamri for clarification on the matter.

‘Not a level playing field’

In a separate Facebook post, lawyer Aidil Khalid claimed that Zamri’s page was “shut down” so the public is only allowed to hear “one side of the story”.

“We are not playing on a level field…accusations are made, claiming that Zamri has fled to Thailand, but he frequently travels back and forth to Thailand because he has business between the two countries,” he claimed.

He also referenced an incident where Zamri was allegedly attacked by two unidentified men on a motorcycle and four others on foot, with Zamri accusing the alleged assailants of acting due to “incitement and a false police report” against him by Rayer.

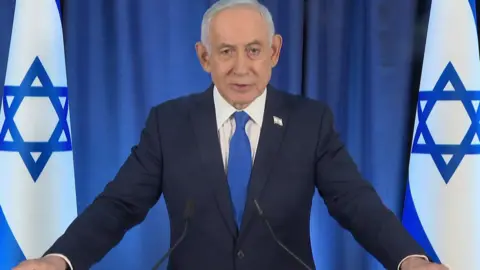

Inspector-General of Police Khalid Ismail

Yesterday, Khalid said Malaysian authorities are working with their Thai counterparts to track down and repatriate Zamri, as well as self-proclaimed land activist Tamim Dahri Abdul Razak.

Zamri is facing two charges - one in connection with his alleged involvement in a Feb 7 gathering in Kuala Lumpur, and the other over supposedly incendiary statements directed at the Indian community.

The first charge is framed under Section 505(b) of the Penal Code on statements constituting public mischief, which carries imprisonment of up to two years, a fine, or both.

The second charge relates to Section 4(1) of the Sedition Act 1948, which criminalises acts or statements with “seditious tendencies”. It carries a maximum prison time of three years, a fine not exceeding RM5,000, or both.

Khalid added that Tamim is expected to face a charge under Section 295 of the Penal Code on the defilement of a sacred object with the intent to wound religious feelings.

Tamim Dahri Abdul Razak allegedly desecrating a site of worship

If found guilty, an offender is liable to imprisonment for up to two years, a fine, or both.

‘Explain charges on Tamim’

In a Facebook post early this morning, lawyer Zainul Rijal Abu Bakar said the decision to charge Tamim should be “carefully reassessed” based on the principles of justice, transparency, and public interest to avoid a perception of a rushed or “influenced” prosecution.

If found guilty, an offender is liable to imprisonment for up to two years, a fine, or both.

‘Explain charges on Tamim’

In a Facebook post early this morning, lawyer Zainul Rijal Abu Bakar said the decision to charge Tamim should be “carefully reassessed” based on the principles of justice, transparency, and public interest to avoid a perception of a rushed or “influenced” prosecution.

Zainul Rijal Abu Bakar

The Malaysian Muslim Lawyers' Association adviser added that if there are elements of inconsistency in prosecutorial action, different treatment of similar cases, or a failure to consider the “full factual circumstances”, such situations can cause questions on whether the legal process is being used “selectively”.

“I believe the decision to charge Tamim should be explained to the public in greater detail, so that there is no doubt that the action was not taken hastily, selectively, or influenced by considerations inconsistent with the principles of justice,” he said.

Expressing similar sentiments, Perlis mufti Asri Zainul Abidin said if Zainul as a “prominent legal practitioner” finds the prosecution of Tamim and Zamri “odd”, the matter is bound to be even more puzzling to the public.

“I’m questioning the fairness and professionalism of the IGP in this issue. Especially since we are in Malaysia, not in India.

“Does our law only ‘show its teeth’ when it comes to Muslims?” he questioned.

“I believe the decision to charge Tamim should be explained to the public in greater detail, so that there is no doubt that the action was not taken hastily, selectively, or influenced by considerations inconsistent with the principles of justice,” he said.

Expressing similar sentiments, Perlis mufti Asri Zainul Abidin said if Zainul as a “prominent legal practitioner” finds the prosecution of Tamim and Zamri “odd”, the matter is bound to be even more puzzling to the public.

“I’m questioning the fairness and professionalism of the IGP in this issue. Especially since we are in Malaysia, not in India.

“Does our law only ‘show its teeth’ when it comes to Muslims?” he questioned.

Perlis mufti Asri Zainul Abidin

Asri also voiced his hope that Khalid will consider “justice for Muslims”, professionalism, the background of the issues involving Zamri and Tamim, as well as the “identity” of the nation.

“In this month of Ramadan, let us pray that our country remains under leadership and management that is just and safeguards the nation’s identity, particularly in matters concerning religion and the Muslim community,” he added.

Asri also voiced his hope that Khalid will consider “justice for Muslims”, professionalism, the background of the issues involving Zamri and Tamim, as well as the “identity” of the nation.

“In this month of Ramadan, let us pray that our country remains under leadership and management that is just and safeguards the nation’s identity, particularly in matters concerning religion and the Muslim community,” he added.

***

Perlis mufti Asri Zainul Abidin asked: “Does our law only ‘show its teeth’ when it comes to Muslims?”

No, Yang Amat Arif, it's the opposite lah. And don't get too excited because it's Hindus (including anti-Muslim Hindu India) on the opposite end - bad for your health.