M Santhananaban

COMMENT | Following the Dec 12 cabinet reshuffle, certain well-known politicians on the verge of political extinction and other diehards appear to have overplayed the issue of minority ethnic Tamil representation in the cabinet.

To provide their grievance greater significance, they have incorrectly implied that ethnic “Indian” representation in the cabinet is absent. That the current Indian appointee is not Tamil-speaking has also been highlighted.

While Tamil is the most widely spoken Indian language in Malaysia, it is not used in cabinet meetings.

Besides, Tamil-speaking leaders have had the exclusive preserve of cabinet positions allotted to Indians for almost seven decades. Yet, even then, they were in an asymmetrical situation, sometimes only commanding a naive position than a no-nonsense one.

With one extraordinary exception, a few of them relinquished their ministerial positions in relatively well-oiled opulent circumstances.

This was a distinct feature that did not apply to the vast majority of ordinary Tamil and other Indian folk.

Entering a discussion of this sort suggests a brazenly ignorant indifference to the cabinet minister currently most identified as of obvious Indian heritage. The sole Indian incumbent, Gobind Singh Deo, is the son of the late Karpal Singh, “the tiger of Jelutong”.

Gobind, like most other enlightened folk in Malaysia, is of the “Malaysia-first” genre. He has, to the best of most people’s knowledge, abided by the highest standards of probity and professionalism. He is now tasked with handling the challenging task of digitalisation.

This is a somewhat problematic project, given our relatively poor state of preparedness and appalling standards of primary and secondary education.

The lack of efficiency, proficiency in English, and operational efficacy of some of our state institutions, also plagued by corruption, does not help.

AI and high-tech digitalisation has to be embraced and regulated to benefit the nation and not just confined to pockets of isolated elitist ecosystems.

This is a huge challenge not only for Gobind but for the entire government, academia, and private sectors.

Ironically, he is called the minister of “digital” - a position that exists nowhere else. It is gracious of him to accept the responsibility to helm a ministry strangely described with an adjective rather than a noun!

Gobind is an excellent choice to reinvigorate Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s relatively fair but flagging year-old administration. He brings professionalism and panache to his ministerial post like his former ministerial colleague, Dr Dzulkefly Ahmad, now back as health minister.

Other new appointees, seasoned holdovers from previous administrations, have also strengthened Anwar’s leadership.

Trenchant Tamil tantrums

Since the July 1955 inaugural Malayan general election, the Indian community of the country has been represented in the federal cabinet by one and sometimes two Tamils.

This representation was of symbolic and substantial significance as not a single federal constituency had a substantial Indian majority electorate.

The appointment of a Tamil minister gave face value and highlighted the pivotal and historical role of not only the Tamils but of the larger Indian community in the political and socioeconomic development of the nation.

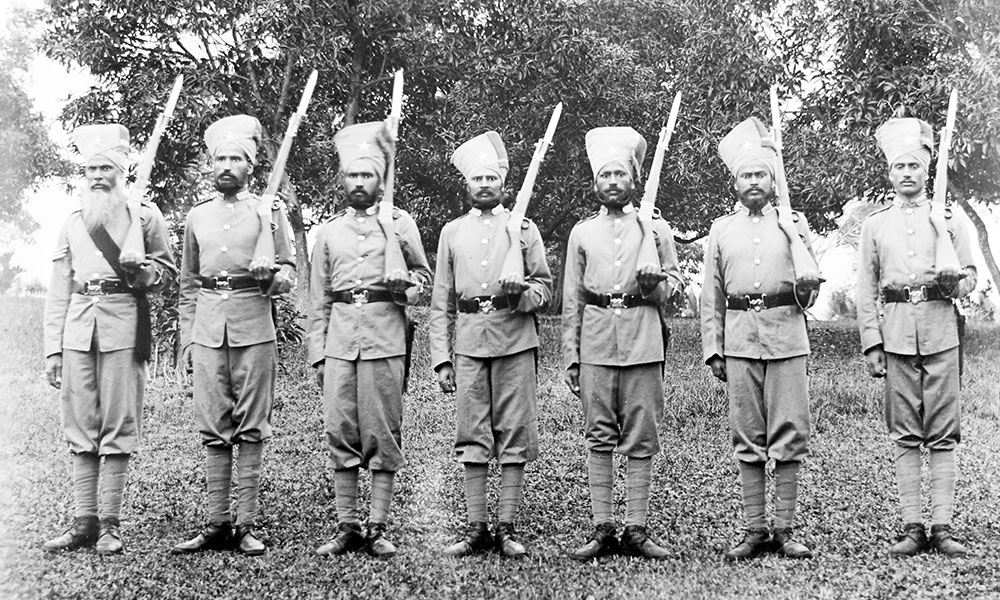

Since the mid-19th century, the British colonialists actively encouraged many Indians to work in the police force, the plantation sector, public administration, and public works services.

The first railway track between Taiping and Port Weld was laid with the participation of Indian, largely Tamil, workers brought in by an enterprising Taiping-based Tamil couple.

Taiping was the capital of Perak, the country’s “senior state” (in British parlance), until 1937. Malaysia’s first public hospital, prison, airport, and museum were also located in Taiping, the most important tin-producing centre in those days.

Hugh Low was a well-regarded British administrator designated as the 4th “British Resident” of Perak. He was a botanist and naturalist who resided not in Taiping but in Kuala Kangsar, the state’s royal town.

Isabella Bird (in the Golden Chersonese, 1967, Oxford edition, which carries an introduction by Wang Gungwu) wrote of Kuala Kangsar (page 348): “I like Kuala Kangsar better than any place that I have been to in Asia.”

This Kuala Kangsar location provided Hugh Low with at least two advantages. He was close to the seat of sovereign power and he could use the freely available royal elephants from the sultan’s palace.

Bird, who was Low’s guest in February 1879, describes her host as follows: “I am inclined to think that Mr Low is happier among the Malays and among his apes and other pets than he would be among civilised Europeans.”

Further, Bird makes several references to the Sikh sentries who provided security, and (on page 320) how the trade of Kuala Kangsar “seems in the hands of the Chinese with a few K***** [alas, a crude, derogatory colloquial term for Indians] among them, and they have a row of shops.”

This anecdotal reference captures the role of the Indian community in the first five years after the signing of the treaty of Pangkor in 1874.

Indian immigration

Jomo Kwame Sundaram, in quoting KS Sandhu, in his article in ‘Indian Communities in Southeast Asia’ (1993 ISEAS) wrote (on page 298) that “of all Indian immigrants to Malaya up to 1941, 1,910 820 had arrived as assisted immigrants while 811, 598 had come unassisted.”

These figures may alarm some of today’s geriatric narrow-minded nationalists, but the reality was that many of those arriving perished in their first year due to accidents, malaria, and other causes.

In 1942, some 100,000 Malayans, mainly Indians, were corralled and sent to serve in Japan’s “death railway” where over half of them perished. In this context, it is intriguing that Malaysia’s “look East” policy was launched exactly four decades later.

At first, the Indians were regarded as transient by the British, who had encouraged the labour migration. However, the latter’s destruction of the economy of India ensured that some Indians had to put down their roots in Malaya to survive.

Indian immigration soared only when the British went into coffee and rubber cultivation. Many of these plantations reaped handsome profits because of the paltry wages paid to their workers.

These Indians cleared the jungles and hacked hills and mountains to build our first railroads. Many were involved in the construction of our roads, buildings, and basic sewerage systems. Some worked as water carriers, punkah wallahs (the servants who handled the hand-operated ceiling fans), “houseboys” (male domestic workers), syces (horse stable workers), and other menial work.

Merdeka

In 1956 the nation’s first prime minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman led a delegation to London to discuss the terms of Malayan independence.

In the talks at Lancaster House, the British obtained two concessions from the Malayan delegation.

The first related to an undertaking that the British would continue to enjoy undisturbed the profits accruing from their investment holdings in Malaya. That meant that the estate employees would not receive any additional monetary benefit for their work in the rubber plantations after independence.

The second concession was that Malaya would be at the forefront of the West’s fight against communism.

Since the start of the Malayan “emergency” in June 1948, the plantation workers were already a proletariat. Their so-called unions appeared to be more aligned with serving British commercial and global interests than the plight of the plantation workers.

In 1957 at the time of Malayan independence, it was therefore not surprising that the mild malleable, largely Tamil labour force was politically represented by refined upright urban-based Tamil leaders rather than some rustic rubber estate revolutionaries.

Those Tamil leaders were given stall seats in the Malaysian cabinet. They seemed preoccupied with facilitating citizenship status for their fellow Indians.

One minister in the first Malayan cabinet, VT Sambanthan, identified himself with the plight of rubber estate workers displaced by the fragmentation of some larger European-owned plantations in the late 1950s.

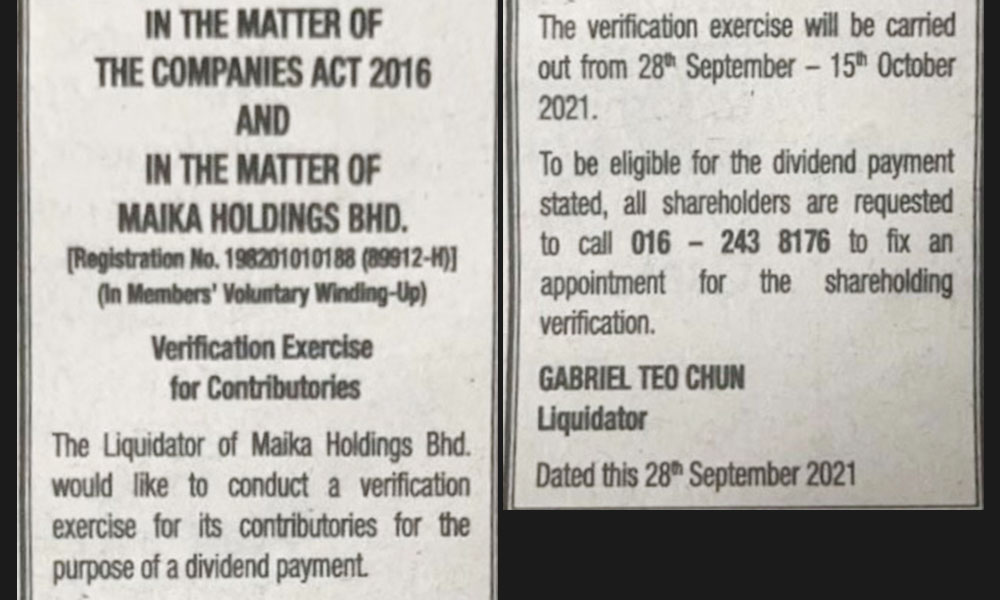

He established a national land cooperative in 1960 to acquire some of these estates. It still operates with a much-reduced land bank.

Ironically, both the ethnic Malay and Indian communities have lately had personages who seemed far more competent in accumulating private fortunes than in managing community-wide assets.

Maika Holdings, like Bank Bumiputra, Tabung Haji, or Felda Global Ventures, had in the past shown a knack for depleting asset value than building it to world-class standards.

Given this background, we need some healthy scepticism when assessing whether the sub-ethnicity of a leader within a community can assure better prospects for that community.

The appointment of a singular Indian member in a cabinet system cannot possibly reflect that community’s vast support for the current government.

Dissatisfaction or misgivings over the lack of recognition of this fact should not morph into a situation where the current Indian incumbent’s professionalism and probity should be questioned.

By all means, if another Indian can be appointed to a ministerial position, it would more realistically reflect the prevailing ratio of Indians in the population.

As Anwar moves into his 14th month in office, the people of Malaysia must trust that the government will become more efficient and effective in delivering the reforms and the resilience the nation needs.

For their part, politicians, professionals, and technocrats must lead and rise above the temptation to resort to corrosive tribalism. They must serve the entire population fairly.

M SANTHANANABAN is a retired Malaysian ambassador with 45 years of public sector experience. This article was first published in Aliran.

When some of them converted to Christianity and joined enmass the evangelical Christian party they were easily taken advantage of by the Chinese.

ReplyDelete