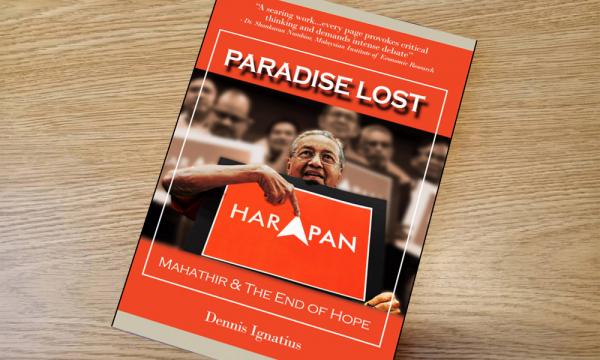

Dennis Ignatius makes his case against Mahathir

S Thayaparan

S ThayaparanAs things turned out, PKR, DAP and Amanah proved spectacularly unsuccessful in controlling Mahathir. He outmanoeuvred them at every turn. He pitted them against each other. He played upon internal rivalries that would have made even Machiavelli envious.

COMMENT | Do not go into this book, thinking that this is merely an exercise in Mahathir bashing. While the machinations of Dr Mahathir Mahathir are meticulously documented, this is also a book about the failings of oppositional political operatives in this country.

The indictment here is that Mahathir has never been able to make the kinds of political plays he has, if it was not for willing acolytes – either in BN or Pakatan Harapan – who falsely assumed they could ride his coattails and remain in power.

As Ignatius did, in his other book "Diplomatically Speaking", he draws not only on personal experience with the personalities involved, but also on sources, gained over decades of loyal service.

He is an insider explaining the arcane workings of the racial and religious politics of the establishment, to outsiders, his countrymen, who do not really know how deep the rabbit hole goes.

For instance, having served under Mahathir and having numerous interactions with former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak, Ignatius makes a clear distinction between the two.

The former a meticulous note-taker, coldly intelligent, shrewd and always waiting for the intended or unintended slight and the latter, a scion of the establishment, easy-going, comfortable around power, a polished diplomat, unfailingly courteous, unlike the pompous and arrogant minister Ignatius was used to dealing with.

This is why, Mahathir, could first systematically neuter institutions and personalities who would constrain him over his long watch and sire creatures who would believe that his blueprint was the only way to maintain power.

This is also why someone, like a disgraced former prime minister, could emerge as a power broker in Umno, enjoying grassroots support.

And forget about Mahathir knowing the Malay mind. Mahathir knows the non-Malay mind probably better than he does the Malay mind. At the very least he knew the non-Malay political establishment mind.

Ignatius writes of how, after decades of demonising the opposition, especially the DAP, which he always used as a proxy for the Chinese community, Mahathir welcomed them into the fold.

His speech, at the Chinese Assembly Hall, resulted in teary eyes. His embracing of the DAP was like “manna from heaven” after decades of abuse.

The brilliance of this book is that all of this happens early on in the book. These snapshots of how the opposition fell under the charm of Mahathir, should have been a warning sign. It is as if Mahathir had inherited a political tabula rasa.

After these first few chapters, Ignatius dives into the history behind the feel-good moments leading up to the election. Interspersed between the breakdown of Harapan, he delves into the failings of the Umno state under Mahathir.

Yes, we get front row seats to the Sheraton Move but this is more than just a collection of how Harapan failed. This book is about why Harapan failed.

He is uncompromising on the players involved, including a young and ambitious Anwar Ibrahim. Anwar’s fate, as Ignatius notes for "disloyalty", was an almost unhinged vengeance on the protégé.

In one memorable passage, Ignatius notes that in conversations with Mahathir when the old maverick was on a diplomatic tour in South America during the tumultuous times before Anwar was kicked out of Umno, Mahathir, overcome with emotion, could not even speak about the betrayal of his protege.

As Ignatius writes, what was Anwar’s crime that he deserved the treatment that he received from the Umno state, that persists till this day.

While he acknowledges Anwar’s reformist credentials, and how he shaped the oppositional political narratives, Ignatius also acknowledges the shrewd way Anwar was embraced by Mahathir and his acolytes because of his Islamic bona fides.

This of course was during the times of his ongoing war with the populist PAS, which in those days, had the remnants of left-wing politics in its Islamic ideology, unlike the Saudi influenced toxicity that it has today.

Keep in mind recent Saudi revelations and acknowledgement that they purposely exported this brand of Islamism.

All this not only played a part in the Islamisation process of institutions but also the state security apparatus. This is an important thread because, as Ignatius writes in his opinion (and one I share), is that the most serious threat to our secular, constitutional democracy is political Islam.

Do not, as Ignatius reminds us, buy into the majority card often played by the ketuanan types. Being in a majority in a democracy does not mean that democratic ideas, values and protections are thrown out the window.

If you as a majority do that, you are not a democratic state but a fascist state. Do attempt to define that as “democracy”.

The rise of the Divine Bureaucracy (a term used by Professor Maznah Mohamad of the National University of Singapore) Jakim, which Mahathir enabled but discovered too late that he could not control, includes its tendrils into the state security apparatus.

Through religious commissars (as Ignatius rightly puts it) to enforce doctrine amongst enlisted men, include Kagat (Armed Forces religious corps) and Baka (Police religious and counselling division).

Ignatius reminds us that Mahathir appointed Brigadier-General Abdul Hamid Zainal Abidin as head of Jakim, (he was the first director of Kagat) and that Major-General Jamil Khir Baharom, the former minister of Islamic affairs, once served as a director of Kagat.

Does anyone else see a problem and pattern here? What we are talking about is how religion is the connective tissue between various institutions of this country.

We are not simply talking about religion "everywhere". What we are talking about is how religion defines the response to threats to national security and the various supposedly independent divisions tasked to guarding such.

So, is it any surprise when the affable and faux reformist Mujahid Yusof Rawa took over and attempted to reform Jakim, he ended up increasing its budget with the help of all those supposedly secular political operatives because, to do otherwise, would spook the Malay establishment?

Now, keep in mind, the book is filled with such historical facts that were forgotten, when Harapan gave the mantle of leadership to Mahathir. A move supported by Ignatius and even myself.

How could we forget such things, especially since Ignatius points out that even on the campaign stump, Mahathir never embraced the reformist agenda?

Hence this book reminds us that we are all complicit in our paradise lost. We are all enablers in the failed Malaysia Baru.

Tawfik Ismail describes Mahathir as the Machiavellian bomoh. It is as good a term as any, but I think of him more as the dark uncle of literature. The archetype, who seduces people from altruistic or righteous paths with quick solutions using warped logic and playing on their insecurities.

You have no idea how entrenched concepts like realpolitik and pragmatism are in political operatives and indeed a certain section of the voting demographic, with the belief of the goal of ultimate good.

The dark uncle always puts forward the benefits of such concepts but never the consequences.

This book reminds us of those consequences.

S THAYAPARAN is Commander (Rtd) of the Royal Malaysian Navy. Fīat jūstitia ruat cælum - "Let justice be done though the heavens fall."

After these first few chapters, Ignatius dives into the history behind the feel-good moments leading up to the election. Interspersed between the breakdown of Harapan, he delves into the failings of the Umno state under Mahathir.

Yes, we get front row seats to the Sheraton Move but this is more than just a collection of how Harapan failed. This book is about why Harapan failed.

He is uncompromising on the players involved, including a young and ambitious Anwar Ibrahim. Anwar’s fate, as Ignatius notes for "disloyalty", was an almost unhinged vengeance on the protégé.

In one memorable passage, Ignatius notes that in conversations with Mahathir when the old maverick was on a diplomatic tour in South America during the tumultuous times before Anwar was kicked out of Umno, Mahathir, overcome with emotion, could not even speak about the betrayal of his protege.

As Ignatius writes, what was Anwar’s crime that he deserved the treatment that he received from the Umno state, that persists till this day.

While he acknowledges Anwar’s reformist credentials, and how he shaped the oppositional political narratives, Ignatius also acknowledges the shrewd way Anwar was embraced by Mahathir and his acolytes because of his Islamic bona fides.

This of course was during the times of his ongoing war with the populist PAS, which in those days, had the remnants of left-wing politics in its Islamic ideology, unlike the Saudi influenced toxicity that it has today.

Keep in mind recent Saudi revelations and acknowledgement that they purposely exported this brand of Islamism.

All this not only played a part in the Islamisation process of institutions but also the state security apparatus. This is an important thread because, as Ignatius writes in his opinion (and one I share), is that the most serious threat to our secular, constitutional democracy is political Islam.

Do not, as Ignatius reminds us, buy into the majority card often played by the ketuanan types. Being in a majority in a democracy does not mean that democratic ideas, values and protections are thrown out the window.

If you as a majority do that, you are not a democratic state but a fascist state. Do attempt to define that as “democracy”.

The rise of the Divine Bureaucracy (a term used by Professor Maznah Mohamad of the National University of Singapore) Jakim, which Mahathir enabled but discovered too late that he could not control, includes its tendrils into the state security apparatus.

Through religious commissars (as Ignatius rightly puts it) to enforce doctrine amongst enlisted men, include Kagat (Armed Forces religious corps) and Baka (Police religious and counselling division).

Ignatius reminds us that Mahathir appointed Brigadier-General Abdul Hamid Zainal Abidin as head of Jakim, (he was the first director of Kagat) and that Major-General Jamil Khir Baharom, the former minister of Islamic affairs, once served as a director of Kagat.

Does anyone else see a problem and pattern here? What we are talking about is how religion is the connective tissue between various institutions of this country.

We are not simply talking about religion "everywhere". What we are talking about is how religion defines the response to threats to national security and the various supposedly independent divisions tasked to guarding such.

So, is it any surprise when the affable and faux reformist Mujahid Yusof Rawa took over and attempted to reform Jakim, he ended up increasing its budget with the help of all those supposedly secular political operatives because, to do otherwise, would spook the Malay establishment?

Now, keep in mind, the book is filled with such historical facts that were forgotten, when Harapan gave the mantle of leadership to Mahathir. A move supported by Ignatius and even myself.

How could we forget such things, especially since Ignatius points out that even on the campaign stump, Mahathir never embraced the reformist agenda?

Hence this book reminds us that we are all complicit in our paradise lost. We are all enablers in the failed Malaysia Baru.

Tawfik Ismail describes Mahathir as the Machiavellian bomoh. It is as good a term as any, but I think of him more as the dark uncle of literature. The archetype, who seduces people from altruistic or righteous paths with quick solutions using warped logic and playing on their insecurities.

You have no idea how entrenched concepts like realpolitik and pragmatism are in political operatives and indeed a certain section of the voting demographic, with the belief of the goal of ultimate good.

The dark uncle always puts forward the benefits of such concepts but never the consequences.

This book reminds us of those consequences.

S THAYAPARAN is Commander (Rtd) of the Royal Malaysian Navy. Fīat jūstitia ruat cælum - "Let justice be done though the heavens fall."

No comments:

Post a Comment