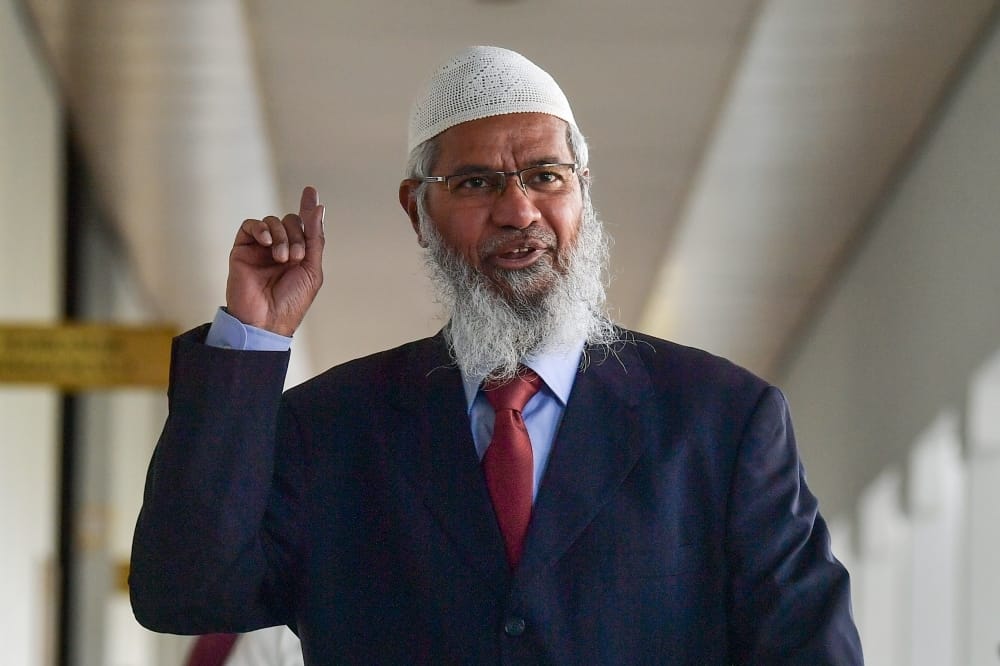

OPINION | Zakir Naik is on His Deathbed?

11 Feb 2026 • 7:30 AM MYT

TheRealNehruism

An award-winning Newswav creator, Bebas News columnist & ex-FMT columnist

Image credit: Malay Mail

If you remember, around September or October last year, Zakir Naik was alleged to be suffering from HIV and AIDS.

Those allegations were serious enough for Naik to issue a public denial and, more significantly, to demand RM10 million in damages from an Indian news portal and its journalist. In a letter of demand issued through his lawyers, Akberdin & Co, Naik accused the portal of defamation, saying its report had tarnished his image, subjected him to ridicule, and implied immoral conduct leading to infection. He demanded a full retraction, a public apology, and monetary compensation, failing which legal action would follow.

Barely four months later, a fresh wave of rumours emerged — this time claiming that Naik was on his deathbed, allegedly hospitalised at Hospital Kuala Lumpur, placed on a ventilator, and “counting his last breath”.

The timing of this new narrative is intriguing. It surfaced just days after his protégé and mentee, Zamri Vinoth, was arrested for organising an anti-temple rally — an incident that coincided with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Malaysia. This detail is not insignificant, considering that Zakir Naik remains a wanted man in India under Modi’s administration.

That Zamri Vinoth’s anti-temple rally, Narendra Modi’s official visit to Malaysia, and the sudden circulation of claims about Zakir Naik being on his deathbed all occurred within the same week is certainly intriguing. Even if these events are entirely unrelated, the intimate — and at times antagonistic — relationships among the personalities involved naturally raise questions. In a political climate as charged and symbolically sensitive as ours, such convergences seldom pass unnoticed, and they inevitably provoke deeper reflection.

As before, the rumours grew loud enough to prompt another formal denial. Speaking to Free Malaysia Today (FMT) through his lawyer, Naik dismissed the claims as “fake news” and “an absurd attempt to tarnish my reputation”. Akberdin Abdul Kader described his client as “hale and hearty”, rubbishing allegations that Naik was critically ill, warded in a highly secure facility, or receiving restricted visitors.

Once again, the explanation offered was familiar: Zakir Naik is the victim of malicious rumours generated by his popularity.

Well, I suppose what Zakir Naik possesses can indeed be described as a species of popularity — for better or worse. His name is recognised by millions worldwide, including in Malaysia. Few religious preachers generate as much attention, influence, and controversy simultaneously.

Yet, it is precisely this repetition of high-profile denials that makes the story unusual.

It is not common for mainstream media outlets to repeatedly report on a public figure denying personal health allegations — especially within such a short span of time. The fact that Zakir Naik has had to publicly reject claims of AIDS, threaten legal action over HIV-related reporting, and now refute deathbed rumours, all within months, naturally provokes curiosity.

It makes one wonder whether, as Zakir insists, there is truly no fire — when there appears to be so much smoke.

After all, Zakir Naik is not the only controversial figure enjoying this form of notoriety. His protégés and ideological allies, such as Zamri Vinoth and Firdaus Wong, are themselves highly visible and polarising.

Yet, no similar health-related rumours trail them. Nor do we see mainstream media carrying their repeated denials. This selective intensity suggests that something about Zakir Naik, in particular, attracts a unique and persistent form of public speculation.

At the rate this peculiar narrative is spreading, even if entirely untrue, it is bound to gain traction simply through repetition.

As Mark Twain famously observed,

“A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes.”

And Joseph Goebbels’ darker formulation reminds us:

“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.”

To prevent what he claims to be false from hardening into perceived truth, Zakir Naik might consider doing something far more effective than issuing statements through lawyers.

Perhaps he should don a tracksuit and running shoes — and participate in a half marathon.

Perhaps this is why visible demonstrations of vitality often carry more persuasive power than press statements. In politics, sport, and public life, images of leaders jogging, playing sports, or engaging energetically with crowds serve as symbolic rebuttals to claims of frailty or decline. They provide a form of visual reassurance that words alone cannot.

For someone in Zakir Naik’s position, such gestures may prove more effective than legal threats or repeated denials. Seeing him actively engaged in public life, physically robust and socially visible, would likely dispel rumours more decisively than any official clarification.

If Dr Mahathir is willing to drive himself to the event celebrating his 100th birthday before joining a bicycle ride covering 8km to 9km to show how healthy and hale he is despite his advanced age, Zakir surely can.

Heck, even after he was admitted for weeks in a hospital after fracturing his hips just recently, that Mahathir went out to have coffee at a mall to show everybody how he is recovering well, is itself a sign of much a video or a picture of one being in the pink of health, is much more effective than simply issuing statements and legal notices.

Zakir may use every word in the dictionary to deny these unsavoury allegations about his health, but nothing would be as persuasive as seeing him hale, hearty, and crossing the finish line like a man half his age.

In the court of public opinion, after all, visible vitality will naturally speak louder than press statements.

Those allegations were serious enough for Naik to issue a public denial and, more significantly, to demand RM10 million in damages from an Indian news portal and its journalist. In a letter of demand issued through his lawyers, Akberdin & Co, Naik accused the portal of defamation, saying its report had tarnished his image, subjected him to ridicule, and implied immoral conduct leading to infection. He demanded a full retraction, a public apology, and monetary compensation, failing which legal action would follow.

Barely four months later, a fresh wave of rumours emerged — this time claiming that Naik was on his deathbed, allegedly hospitalised at Hospital Kuala Lumpur, placed on a ventilator, and “counting his last breath”.

The timing of this new narrative is intriguing. It surfaced just days after his protégé and mentee, Zamri Vinoth, was arrested for organising an anti-temple rally — an incident that coincided with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Malaysia. This detail is not insignificant, considering that Zakir Naik remains a wanted man in India under Modi’s administration.

That Zamri Vinoth’s anti-temple rally, Narendra Modi’s official visit to Malaysia, and the sudden circulation of claims about Zakir Naik being on his deathbed all occurred within the same week is certainly intriguing. Even if these events are entirely unrelated, the intimate — and at times antagonistic — relationships among the personalities involved naturally raise questions. In a political climate as charged and symbolically sensitive as ours, such convergences seldom pass unnoticed, and they inevitably provoke deeper reflection.

As before, the rumours grew loud enough to prompt another formal denial. Speaking to Free Malaysia Today (FMT) through his lawyer, Naik dismissed the claims as “fake news” and “an absurd attempt to tarnish my reputation”. Akberdin Abdul Kader described his client as “hale and hearty”, rubbishing allegations that Naik was critically ill, warded in a highly secure facility, or receiving restricted visitors.

Once again, the explanation offered was familiar: Zakir Naik is the victim of malicious rumours generated by his popularity.

Well, I suppose what Zakir Naik possesses can indeed be described as a species of popularity — for better or worse. His name is recognised by millions worldwide, including in Malaysia. Few religious preachers generate as much attention, influence, and controversy simultaneously.

Yet, it is precisely this repetition of high-profile denials that makes the story unusual.

It is not common for mainstream media outlets to repeatedly report on a public figure denying personal health allegations — especially within such a short span of time. The fact that Zakir Naik has had to publicly reject claims of AIDS, threaten legal action over HIV-related reporting, and now refute deathbed rumours, all within months, naturally provokes curiosity.

It makes one wonder whether, as Zakir insists, there is truly no fire — when there appears to be so much smoke.

After all, Zakir Naik is not the only controversial figure enjoying this form of notoriety. His protégés and ideological allies, such as Zamri Vinoth and Firdaus Wong, are themselves highly visible and polarising.

Yet, no similar health-related rumours trail them. Nor do we see mainstream media carrying their repeated denials. This selective intensity suggests that something about Zakir Naik, in particular, attracts a unique and persistent form of public speculation.

At the rate this peculiar narrative is spreading, even if entirely untrue, it is bound to gain traction simply through repetition.

As Mark Twain famously observed,

“A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes.”

And Joseph Goebbels’ darker formulation reminds us:

“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.”

To prevent what he claims to be false from hardening into perceived truth, Zakir Naik might consider doing something far more effective than issuing statements through lawyers.

Perhaps he should don a tracksuit and running shoes — and participate in a half marathon.

Perhaps this is why visible demonstrations of vitality often carry more persuasive power than press statements. In politics, sport, and public life, images of leaders jogging, playing sports, or engaging energetically with crowds serve as symbolic rebuttals to claims of frailty or decline. They provide a form of visual reassurance that words alone cannot.

For someone in Zakir Naik’s position, such gestures may prove more effective than legal threats or repeated denials. Seeing him actively engaged in public life, physically robust and socially visible, would likely dispel rumours more decisively than any official clarification.

If Dr Mahathir is willing to drive himself to the event celebrating his 100th birthday before joining a bicycle ride covering 8km to 9km to show how healthy and hale he is despite his advanced age, Zakir surely can.

Heck, even after he was admitted for weeks in a hospital after fracturing his hips just recently, that Mahathir went out to have coffee at a mall to show everybody how he is recovering well, is itself a sign of much a video or a picture of one being in the pink of health, is much more effective than simply issuing statements and legal notices.

Zakir may use every word in the dictionary to deny these unsavoury allegations about his health, but nothing would be as persuasive as seeing him hale, hearty, and crossing the finish line like a man half his age.

In the court of public opinion, after all, visible vitality will naturally speak louder than press statements.

No comments:

Post a Comment