Zahid’s DNAA sparks calls to split AG’s roles as govt’s adviser and prosecutor — here’s why it matters

Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi at the Kuala Lumpur High Court, September 4, 2023. — Picture by Ahmad Zamzahuri

Tuesday, 12 Sep 2023 7:00 AM MYT

KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 12 — The prosecution’s decision last week to discontinue a corruption trial involving 47 charges against Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi has reignited long-standing calls for reforms to ensure that the attorney general (AG) does not act as both the government’s legal adviser and the public prosecutor.

But why is it important to split up the AG’s dual roles? Why is it necessary and how is it relevant?

Furthermore, years after this suggestion was first made, how might Malaysia actually achieve this? Here’s what legal experts told Malay Mail.

Criminal lawyer Tiara Katrina Fuad said it is important to separate the AG’s current dual roles as it would address concerns of alleged selective prosecution, and would also enable institutional independence that is based on the AG’s office’s structure and that is not dependent on the independence of the individual holding the AG’s position.

“Because right now there are a lot of claims of selective prosecution, why are they claiming that? Because you look at the duties of the AG, on top of prosecuting cases, is also to advise the government of the day.

“How is the AG appointed? He’s appointed indirectly by the prime minister. So you have a person — who is appointed indirectly by the PM — who is also deciding on who to prosecute, so the allegation or complaint is there’s a real risk of conflict of interest,” she said when contacted recently.

“In this scenario where you have this dual role, there is the risk that the AG will feel beholden to the government and therefore in exercising his duties as a public prosecutor does it in a way that is aligned with the government. That’s why it’s important to separate, it addresses those concerns about selective prosecution.”

“Because if it is separated, then the person who advises the government is not going to be the same person who decides who to prosecute and in which cases to withdraw charges, so that will create a higher degree of independence in the office of the public prosecutor, that’s why it’s important,” she added.

Asked if it is merely about perception and if there can be independence without splitting up the AG’s dual roles, Tiara Katrina said the separation of the AG’s advisory and prosecuting roles was necessary to set up a structure which would promote independence.

“It’s about institutional independence. You may have a particular case where you have a particular AG that is independent on a case-to-case basis. But what we would want is to ensure enough separation between the institutions so it doesn’t depend on the individual AG, because the structure is outlined in such a way that already makes it conducive for a greater degree of independence,” she said.

Mohamad Hafiz Hassan, a law lecturer at the Multimedia University who teaches civil procedure and criminal procedure, said the AG’s dual roles could give rise to views that the AG has a conflict of interests.

“The AG is first, the adviser of the government, he is also the public prosecutor, whereas as a public prosecutor, he may prosecute a member of the government. So that puts him in a difficult position where he has to decide whether to charge or discontinue the charge,” he said.

“People will say he is in a conflicted position because as a public prosecutor, he acts in the best interests of the public; as a legal adviser, he acts in the interest of the government. So when he’s prosecuting for example a minister in government or political leader, he acts in the best interest of the public, so he must discharge duty in good faith, so there shouldn’t be any political consideration whether to charge or to discontinue, that’s why the call for separate roles is valid.”

He said other jurisdictions such as the UK, Hong Kong and Australia provide for such separate roles, noting that Australia — which is a federation and a country based on common law like Malaysia — is a good example.

For the Australian model, Hafiz said its AG is an MP and appointed by the Australian governor-general on the prime minister’s advice, and that its equivalent of an AG — known as the First Law Officer — acts as the government’s principal legal adviser and also delegates some powers to other law officers.

Meanwhile, its equivalent of a solicitor general (SG) — known as the Second Law Officer — acts as the government’s lawyer and plays the role of giving opinions on questions of law referred to him by the AG and performing other functions as requested by the AG.

Hafiz said that Australia has a Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) which independently carries out prosecutions and that the CDPP’s office — despite being part of the AG’s portfolio — operates independently of both the AG and the political process.

While Australian laws grant the AG the power to issue written directions or guidelines to the CDPP, the AG is required to first consult with the CDPP before issuing directions and such directions have to be tabled in Australia’s Parliament, and with the CDPP bound by the AG’s directions or guidelines, Hafiz said.

“Since the CDPP was established and up to 2019, only seven directions have been issued,” he said.

Former Malaysian Bar president Ragunath Kesavan said the AG’s roles should be split up to ensure greater professionalism but he said “that alone will not ensure complete independence”.

“End of the day, it’s a question of political will, whether to interfere or not to interfere,” he said.

What does the government think?

On December 3, 2022, the Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Seri Azalina Othman Said upon her appointment said her law and institutional reform portfolio’s foremost focus is to make the necessary amendments to laws to make them relevant to our times, citing the separation of power of the AG and public prosecutor to preserve the independence of the public prosecutor’s discretion as an example.

On August 18, Azalina was reported saying that the Federal Constitution and about 19 existing laws would have to be amended to implement the proposed separation of powers between the AG and the public prosecutor, and that it would also involve additional government spending.

Azalina had also reportedly said the government is set to undertake a comprehensive study within a year before finalising the proposed separation of powers for the AG and public prosecutor.

On September 8, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim was reported saying that the proposal to separate the AG’s and public prosecutor’s roles had been presented to the Cabinet several months ago, and that it has been referred to a parliamentary select committee for further study, adding that the process to implement this would require high costs and would also take time while also requiring a two-thirds majority support in Parliament.

Previously on March 28, Anwar was reported saying in the Dewan Rakyat that there would be an additional RM300 million involved for the implementation of such a proposal.

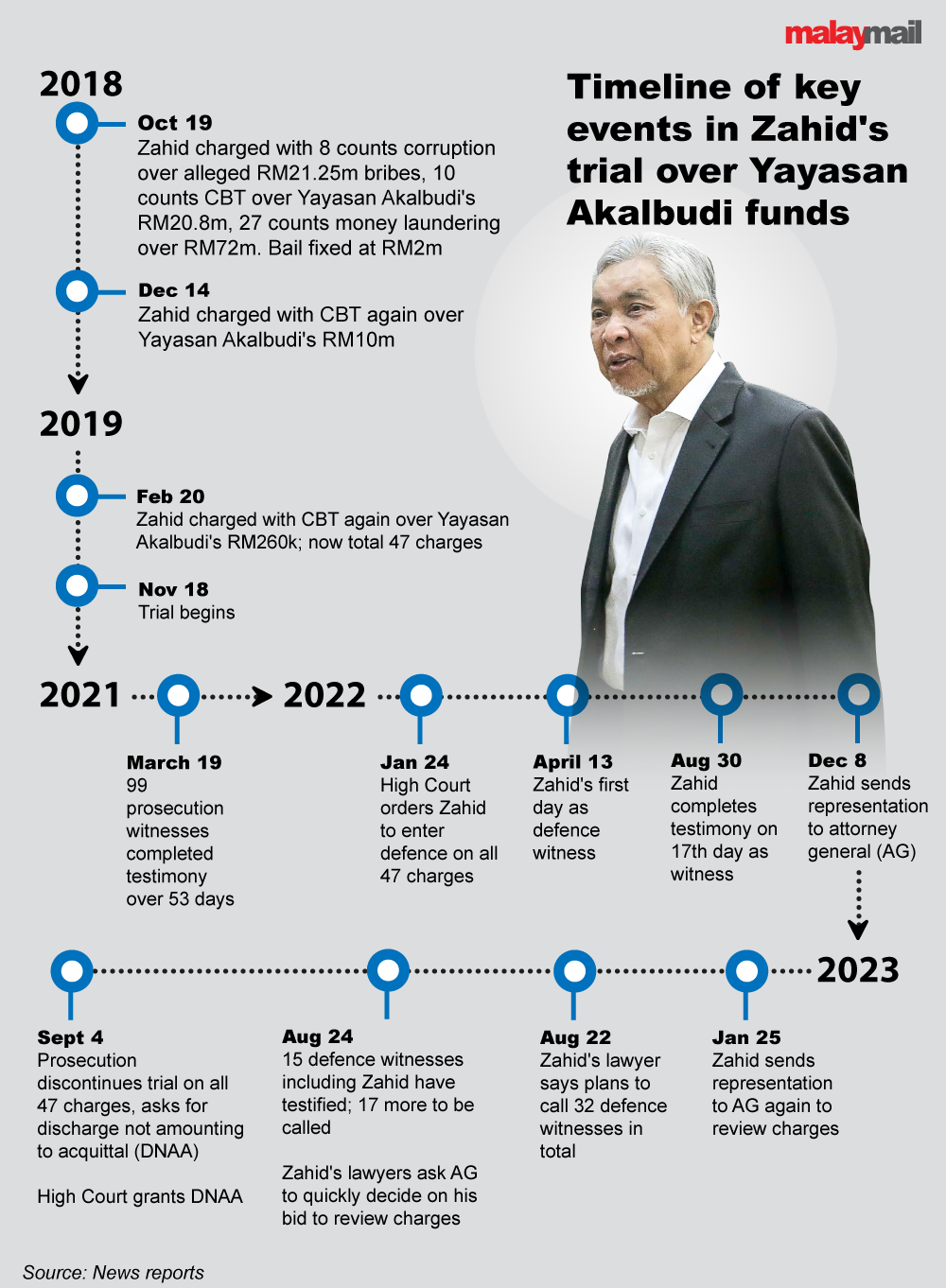

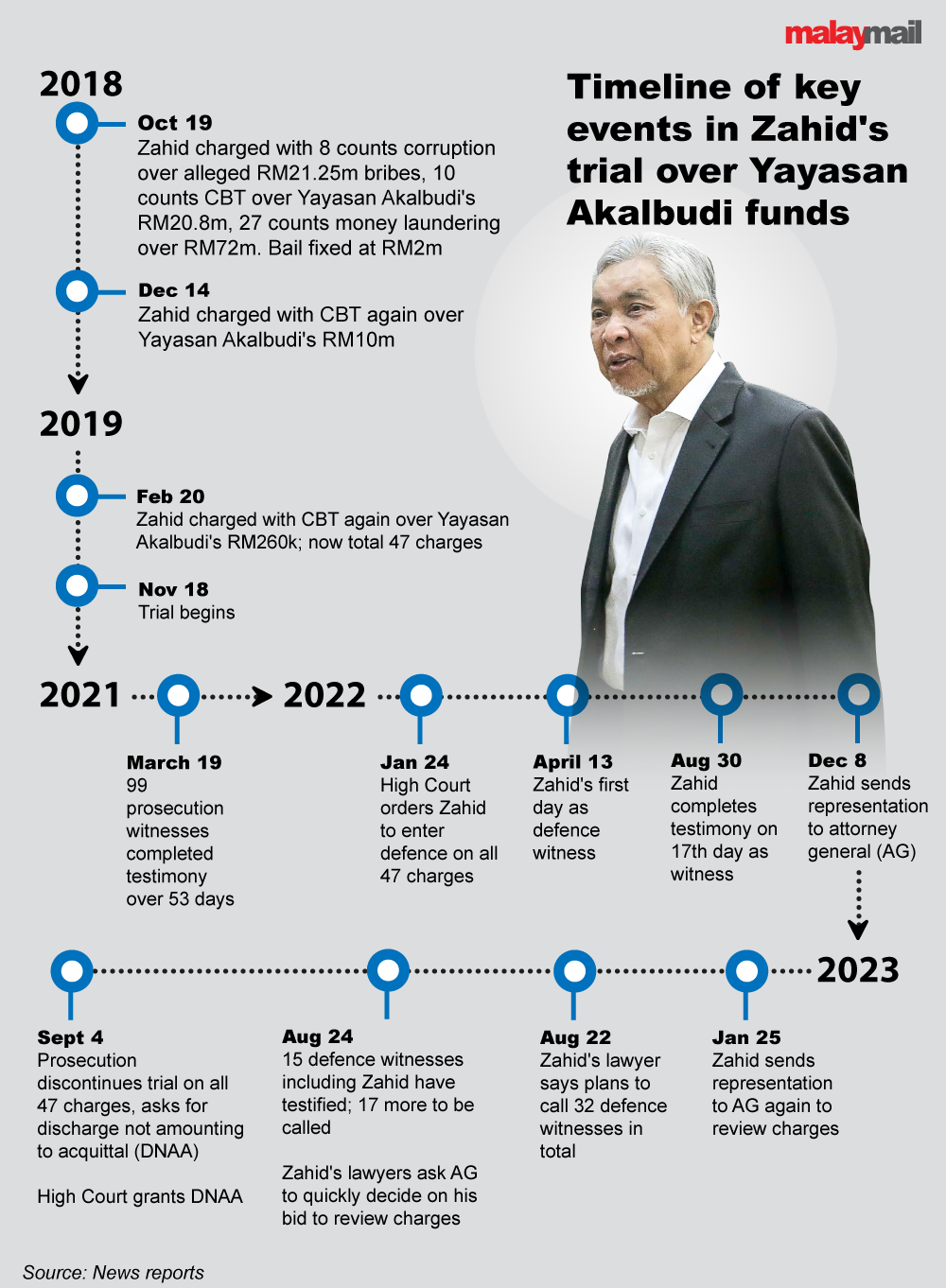

Zahid, who is also Umno president and Barisan Nasional chairman, faced 47 charges in this case, namely, 12 counts of criminal breach of trust in relation to over RM31 million of his charitable organisation Yayasan Akalbudi’s funds, 27 counts of money laundering, and eight counts of bribery charges of over RM21.25 million in alleged bribes.

After the prosecution on September 4 discontinued Zahid’s trial, his lawyers immediately made a joint statement that reiterated Zahid’s claim during the trial that this case allegedly resulted from “political prosecution”, and that he had been charged months after he refused to comply with then prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s June 2018 request to dissolve Umno to avoid facing consequences.

Electoral reform group Bersih had on September 4 said there must be a separation of the attorney general as a political appointee advising the government from his current dual role as the public prosecutor as the latter’s powers to begin or drop criminal charges can be abused or weaponised for political reasons, while the Malaysian Bar on September 7 said these dual roles must be separated to create true independence in the public prosecutor’s exercise of prosecutorial powers to be free from any influence of the executive branch of government.

On September 8, newly-appointed AG Datuk Ahmad Terrirudin Mohd Salleh in a six-page statement responded to criticism over the prosecution’s dropping of Zahid’s trial, saying that any exercise of the AG’s discretion to discontinue trials is not simply done or due to interference from any quarters but will purely be after the AG takes into account justice for all and for the administration of justice.

Among other things, the AG reiterated the 11 reasons provided by the prosecution when it discontinued the trial and sought a discharge not amounting to an acquittal (DNAA) against Zahid, including the need to temporarily stop the trial until more comprehensive investigations are carried out in light of alleged new evidence and to prevent miscarriage of justice. A DNAA means that an accused person can be charged again on the same charges.

In that same September 8 statement, the AG said the AG’s Chambers hopes for an end to speculation on Zahid’s case as both the AGC and investigators are still investigating all new evidence that arose in this case, adding that any decision on whether to charge Zahid again or charge others related to the case will be made after more detailed and comprehensive investigations are complete.

Yesterday, the Malaysian United Democratic Alliance (Muda) and the Socialist Party of Malaysia (PSM) sent a letter to the AG and listed several demands that they want to be fulfilled within five working days or before September 18, including providing a clear timeline for the separation of the AG’s and public prosecutor’s roles to minimise any conflict of interest. The two parties said they will carry out a protest if no satisfactory response is provided before September 18.

This is Part 3 of Malay Mail's series on how the law works for discontinuing of trial, discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA), acquittals and why institutional reforms are necessary. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

Tuesday, 12 Sep 2023 7:00 AM MYT

KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 12 — The prosecution’s decision last week to discontinue a corruption trial involving 47 charges against Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi has reignited long-standing calls for reforms to ensure that the attorney general (AG) does not act as both the government’s legal adviser and the public prosecutor.

But why is it important to split up the AG’s dual roles? Why is it necessary and how is it relevant?

Furthermore, years after this suggestion was first made, how might Malaysia actually achieve this? Here’s what legal experts told Malay Mail.

Criminal lawyer Tiara Katrina Fuad said it is important to separate the AG’s current dual roles as it would address concerns of alleged selective prosecution, and would also enable institutional independence that is based on the AG’s office’s structure and that is not dependent on the independence of the individual holding the AG’s position.

“Because right now there are a lot of claims of selective prosecution, why are they claiming that? Because you look at the duties of the AG, on top of prosecuting cases, is also to advise the government of the day.

“How is the AG appointed? He’s appointed indirectly by the prime minister. So you have a person — who is appointed indirectly by the PM — who is also deciding on who to prosecute, so the allegation or complaint is there’s a real risk of conflict of interest,” she said when contacted recently.

“In this scenario where you have this dual role, there is the risk that the AG will feel beholden to the government and therefore in exercising his duties as a public prosecutor does it in a way that is aligned with the government. That’s why it’s important to separate, it addresses those concerns about selective prosecution.”

“Because if it is separated, then the person who advises the government is not going to be the same person who decides who to prosecute and in which cases to withdraw charges, so that will create a higher degree of independence in the office of the public prosecutor, that’s why it’s important,” she added.

Asked if it is merely about perception and if there can be independence without splitting up the AG’s dual roles, Tiara Katrina said the separation of the AG’s advisory and prosecuting roles was necessary to set up a structure which would promote independence.

“It’s about institutional independence. You may have a particular case where you have a particular AG that is independent on a case-to-case basis. But what we would want is to ensure enough separation between the institutions so it doesn’t depend on the individual AG, because the structure is outlined in such a way that already makes it conducive for a greater degree of independence,” she said.

Mohamad Hafiz Hassan, a law lecturer at the Multimedia University who teaches civil procedure and criminal procedure, said the AG’s dual roles could give rise to views that the AG has a conflict of interests.

“The AG is first, the adviser of the government, he is also the public prosecutor, whereas as a public prosecutor, he may prosecute a member of the government. So that puts him in a difficult position where he has to decide whether to charge or discontinue the charge,” he said.

“People will say he is in a conflicted position because as a public prosecutor, he acts in the best interests of the public; as a legal adviser, he acts in the interest of the government. So when he’s prosecuting for example a minister in government or political leader, he acts in the best interest of the public, so he must discharge duty in good faith, so there shouldn’t be any political consideration whether to charge or to discontinue, that’s why the call for separate roles is valid.”

He said other jurisdictions such as the UK, Hong Kong and Australia provide for such separate roles, noting that Australia — which is a federation and a country based on common law like Malaysia — is a good example.

For the Australian model, Hafiz said its AG is an MP and appointed by the Australian governor-general on the prime minister’s advice, and that its equivalent of an AG — known as the First Law Officer — acts as the government’s principal legal adviser and also delegates some powers to other law officers.

Meanwhile, its equivalent of a solicitor general (SG) — known as the Second Law Officer — acts as the government’s lawyer and plays the role of giving opinions on questions of law referred to him by the AG and performing other functions as requested by the AG.

Hafiz said that Australia has a Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) which independently carries out prosecutions and that the CDPP’s office — despite being part of the AG’s portfolio — operates independently of both the AG and the political process.

While Australian laws grant the AG the power to issue written directions or guidelines to the CDPP, the AG is required to first consult with the CDPP before issuing directions and such directions have to be tabled in Australia’s Parliament, and with the CDPP bound by the AG’s directions or guidelines, Hafiz said.

“Since the CDPP was established and up to 2019, only seven directions have been issued,” he said.

Former Malaysian Bar president Ragunath Kesavan said the AG’s roles should be split up to ensure greater professionalism but he said “that alone will not ensure complete independence”.

“End of the day, it’s a question of political will, whether to interfere or not to interfere,” he said.

What does the government think?

On December 3, 2022, the Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Seri Azalina Othman Said upon her appointment said her law and institutional reform portfolio’s foremost focus is to make the necessary amendments to laws to make them relevant to our times, citing the separation of power of the AG and public prosecutor to preserve the independence of the public prosecutor’s discretion as an example.

On August 18, Azalina was reported saying that the Federal Constitution and about 19 existing laws would have to be amended to implement the proposed separation of powers between the AG and the public prosecutor, and that it would also involve additional government spending.

Azalina had also reportedly said the government is set to undertake a comprehensive study within a year before finalising the proposed separation of powers for the AG and public prosecutor.

On September 8, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim was reported saying that the proposal to separate the AG’s and public prosecutor’s roles had been presented to the Cabinet several months ago, and that it has been referred to a parliamentary select committee for further study, adding that the process to implement this would require high costs and would also take time while also requiring a two-thirds majority support in Parliament.

Previously on March 28, Anwar was reported saying in the Dewan Rakyat that there would be an additional RM300 million involved for the implementation of such a proposal.

Zahid, who is also Umno president and Barisan Nasional chairman, faced 47 charges in this case, namely, 12 counts of criminal breach of trust in relation to over RM31 million of his charitable organisation Yayasan Akalbudi’s funds, 27 counts of money laundering, and eight counts of bribery charges of over RM21.25 million in alleged bribes.

After the prosecution on September 4 discontinued Zahid’s trial, his lawyers immediately made a joint statement that reiterated Zahid’s claim during the trial that this case allegedly resulted from “political prosecution”, and that he had been charged months after he refused to comply with then prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s June 2018 request to dissolve Umno to avoid facing consequences.

Electoral reform group Bersih had on September 4 said there must be a separation of the attorney general as a political appointee advising the government from his current dual role as the public prosecutor as the latter’s powers to begin or drop criminal charges can be abused or weaponised for political reasons, while the Malaysian Bar on September 7 said these dual roles must be separated to create true independence in the public prosecutor’s exercise of prosecutorial powers to be free from any influence of the executive branch of government.

On September 8, newly-appointed AG Datuk Ahmad Terrirudin Mohd Salleh in a six-page statement responded to criticism over the prosecution’s dropping of Zahid’s trial, saying that any exercise of the AG’s discretion to discontinue trials is not simply done or due to interference from any quarters but will purely be after the AG takes into account justice for all and for the administration of justice.

Among other things, the AG reiterated the 11 reasons provided by the prosecution when it discontinued the trial and sought a discharge not amounting to an acquittal (DNAA) against Zahid, including the need to temporarily stop the trial until more comprehensive investigations are carried out in light of alleged new evidence and to prevent miscarriage of justice. A DNAA means that an accused person can be charged again on the same charges.

In that same September 8 statement, the AG said the AG’s Chambers hopes for an end to speculation on Zahid’s case as both the AGC and investigators are still investigating all new evidence that arose in this case, adding that any decision on whether to charge Zahid again or charge others related to the case will be made after more detailed and comprehensive investigations are complete.

Yesterday, the Malaysian United Democratic Alliance (Muda) and the Socialist Party of Malaysia (PSM) sent a letter to the AG and listed several demands that they want to be fulfilled within five working days or before September 18, including providing a clear timeline for the separation of the AG’s and public prosecutor’s roles to minimise any conflict of interest. The two parties said they will carry out a protest if no satisfactory response is provided before September 18.

This is Part 3 of Malay Mail's series on how the law works for discontinuing of trial, discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA), acquittals and why institutional reforms are necessary. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

No comments:

Post a Comment