Bridget Welsh

COMMENT | The results of the Malacca polls are in – Umno/BN won handily, securing a two-thirds majority of 21 out of 28 seats.

Umno is back in the driving seat in government at the state level, positioning itself for a return to national power in the coming GE15 federal elections.

Pakatan Harapan was soundly defeated – not just by BN/Umno but also by Perikatan Nasional (PN), the coalition that took the government from them in the Sheraton Move in February 2020. What happened and why?

Drawing from fieldwork in Malacca, and earlier pieces that drew attention to why PN gained ground especially in the last few days of the campaign, this piece offers a preliminary analysis of the results.

Here the focus is on ethnic voting patterns, using macro seat analysis (rather than the more detailed polling station and saluran results which allow for assessments of ethnicity, gender and class voting). A microanalysis will follow.

This initial look at voting behaviour shows that while Harapan was soundly defeated, the vote was neither an endorsement for Umno/BN nor enthusiasm with any of the political alternatives on offer.

The biggest winner in terms of vote gain was Muhyiddin Yassin’s Bersatu.

Massive turnout decline

The Malacca result is the lowest turnout in history for a Malacca election, dropping from 85 percent to 66 percent. As detailed in Table 1, the pattern of turnout decline among the different ethnic communities shows decisively that Harapan lost support in its ethnic political base, traditionally non-Malays.

Nearly one-third (estimated 29 percent) of Chinese and Indian Malacca voters, and over a third of others (estimated 34 percent) did not come to vote.

This was a conscious decision among voters that they are unsatisfied not only with Harapan but all of the alternatives.

This was not just about Covid or a home protest – which can account for some dissatisfied with frogging and Harapan’s poor leadership decisions – but also highlights broader dismay with all options on offer.

In looking at the effect of lower turnout on the individual seat results, turnout declines from GE14 to the state polls were higher than the final majorities in all but four seats (Lendu, Taboh Naning, Bandar Hilir and Merlimau) showing emphatically that turnout affected the outcomes.

Malacca’s election was indeed competitive and greater mobilisation would have made for very different results.

All of the defeats by Harapan were influenced by the turnout. Pengkalan Batu, lost by a mere 131 votes, is illustrative. Serkam was even closer, at a difference of 79 votes, but in this contest, Harapan was not in the running as PAS and Umno battled it out with Umno winning.

The lacklustre messaging of all the campaigns and consequential voter disengagement was evident. Harapan in particular failed to inspire its base.

No Umno electoral renewal

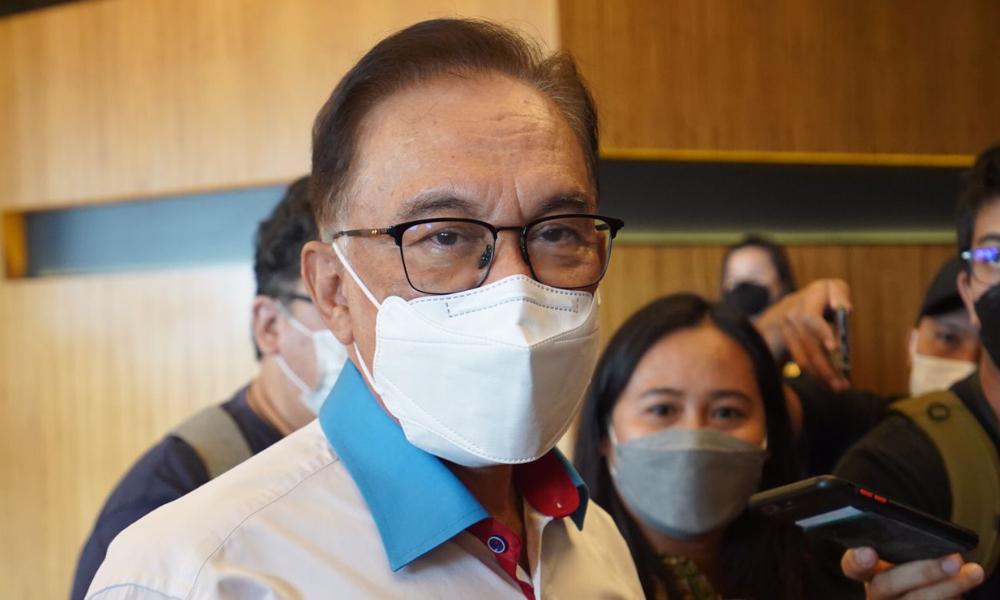

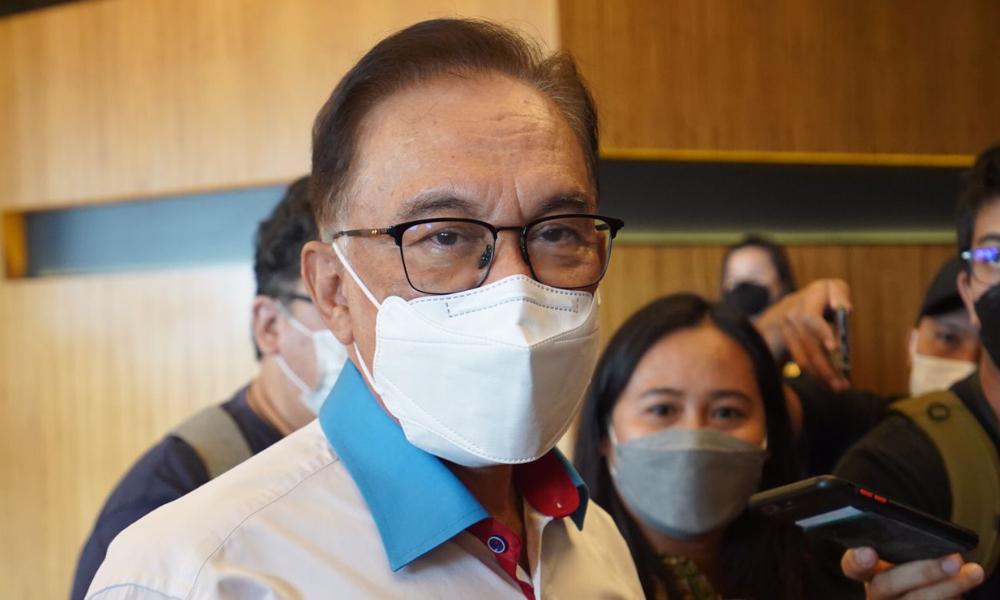

This election has two important political outcomes at the party level. The first is the defeat of Harapan, especially the wipe-out of Anwar Ibrahim’s party in all of the 11 seats it contested. Second is the rise of Bersatu as a stronger political force nationally.

COMMENT | The results of the Malacca polls are in – Umno/BN won handily, securing a two-thirds majority of 21 out of 28 seats.

Umno is back in the driving seat in government at the state level, positioning itself for a return to national power in the coming GE15 federal elections.

Pakatan Harapan was soundly defeated – not just by BN/Umno but also by Perikatan Nasional (PN), the coalition that took the government from them in the Sheraton Move in February 2020. What happened and why?

Drawing from fieldwork in Malacca, and earlier pieces that drew attention to why PN gained ground especially in the last few days of the campaign, this piece offers a preliminary analysis of the results.

Here the focus is on ethnic voting patterns, using macro seat analysis (rather than the more detailed polling station and saluran results which allow for assessments of ethnicity, gender and class voting). A microanalysis will follow.

This initial look at voting behaviour shows that while Harapan was soundly defeated, the vote was neither an endorsement for Umno/BN nor enthusiasm with any of the political alternatives on offer.

The biggest winner in terms of vote gain was Muhyiddin Yassin’s Bersatu.

Massive turnout decline

The Malacca result is the lowest turnout in history for a Malacca election, dropping from 85 percent to 66 percent. As detailed in Table 1, the pattern of turnout decline among the different ethnic communities shows decisively that Harapan lost support in its ethnic political base, traditionally non-Malays.

Nearly one-third (estimated 29 percent) of Chinese and Indian Malacca voters, and over a third of others (estimated 34 percent) did not come to vote.

This was a conscious decision among voters that they are unsatisfied not only with Harapan but all of the alternatives.

This was not just about Covid or a home protest – which can account for some dissatisfied with frogging and Harapan’s poor leadership decisions – but also highlights broader dismay with all options on offer.

In looking at the effect of lower turnout on the individual seat results, turnout declines from GE14 to the state polls were higher than the final majorities in all but four seats (Lendu, Taboh Naning, Bandar Hilir and Merlimau) showing emphatically that turnout affected the outcomes.

Malacca’s election was indeed competitive and greater mobilisation would have made for very different results.

All of the defeats by Harapan were influenced by the turnout. Pengkalan Batu, lost by a mere 131 votes, is illustrative. Serkam was even closer, at a difference of 79 votes, but in this contest, Harapan was not in the running as PAS and Umno battled it out with Umno winning.

The lacklustre messaging of all the campaigns and consequential voter disengagement was evident. Harapan in particular failed to inspire its base.

No Umno electoral renewal

This election has two important political outcomes at the party level. The first is the defeat of Harapan, especially the wipe-out of Anwar Ibrahim’s party in all of the 11 seats it contested. Second is the rise of Bersatu as a stronger political force nationally.

PKR president Anwar Ibrahim

Before looking at these, it is useful to debunk other interpretations of the outcome.

Umno did gain a larger share of the votes, 30 percent compared to 25 percent in GE14. This is a modest gain compared to the gain of five seats to 18 from 13. Umno won eight of its seats by small margins (less than 5 percent of the voters), scrapping through in Serkam, Duyong, Paya Rumput, Sungai Udang and Pengkalan Batu.

As noted in Table 2 below, Umno lost an estimated 4 percent support among Malay voters. To interpret that Umno is back electorally would be an overstatement as its support remains far below what it was in GE12 in 2013.

Umno’s electoral victory was given to them by Harapan in their political shortcomings.

While coming close to winning in Serkam and taking a sizeable share of the vote in Duyong, PAS lost in its share of the popular vote from 11 percent to 7 percent.

In 2018, PAS contested 23 seats. This time it was only eight seats – inevitably a drop in the overall percentage. To understand PAS’ support changes it is useful to look at its comparative strongholds.

In Serkam, PAS gained 18 percent of the vote compared to GE14, in Duyong only 5 percent. PAS did gain in particular seats, but it still cannot win on its own and did not make gains across Malacca as a whole.

A third overinterpreted view is that MCA and MIC are back politically. They are in terms of the seats won, two and one respectively. Yet, in terms of support, neither made meaningful gains in the popular vote.

In fact, MCA lost ground marginally, from 10 percent to 8 percent. This is also due in part to fewer seats contested but speaks to the fact that it continues to have a weak political base. It (and DAP) lost Bemban to Bersatu.

Harapan erosion

What then are the major electoral changes in party fortunes? While Amanah lost all but one of its seats contested, that of its former chief minister Adly Zahari, it retained the same share, 8 percent, of the vote contesting the same number of seats.

Before looking at these, it is useful to debunk other interpretations of the outcome.

Umno did gain a larger share of the votes, 30 percent compared to 25 percent in GE14. This is a modest gain compared to the gain of five seats to 18 from 13. Umno won eight of its seats by small margins (less than 5 percent of the voters), scrapping through in Serkam, Duyong, Paya Rumput, Sungai Udang and Pengkalan Batu.

As noted in Table 2 below, Umno lost an estimated 4 percent support among Malay voters. To interpret that Umno is back electorally would be an overstatement as its support remains far below what it was in GE12 in 2013.

Umno’s electoral victory was given to them by Harapan in their political shortcomings.

While coming close to winning in Serkam and taking a sizeable share of the vote in Duyong, PAS lost in its share of the popular vote from 11 percent to 7 percent.

In 2018, PAS contested 23 seats. This time it was only eight seats – inevitably a drop in the overall percentage. To understand PAS’ support changes it is useful to look at its comparative strongholds.

In Serkam, PAS gained 18 percent of the vote compared to GE14, in Duyong only 5 percent. PAS did gain in particular seats, but it still cannot win on its own and did not make gains across Malacca as a whole.

A third overinterpreted view is that MCA and MIC are back politically. They are in terms of the seats won, two and one respectively. Yet, in terms of support, neither made meaningful gains in the popular vote.

In fact, MCA lost ground marginally, from 10 percent to 8 percent. This is also due in part to fewer seats contested but speaks to the fact that it continues to have a weak political base. It (and DAP) lost Bemban to Bersatu.

Harapan erosion

What then are the major electoral changes in party fortunes? While Amanah lost all but one of its seats contested, that of its former chief minister Adly Zahari, it retained the same share, 8 percent, of the vote contesting the same number of seats.

Former chief minister Adly Zahari

PKR lost only a small share of the vote, from 10 percent to 9 percent in its wiped-out seat losses. If either party had pulled home more of its supporters it would have been able to secure more victories.

Interviews in the field showed that PKR hurt itself. Of all the parties in Harapan, PKR’s machinery was the weakest, most fractured on the ground. Some of its own party members stayed home.

Paya Rumput, where Shamsul Iskandar contested was ripe for victory with large numbers of young voters, was lost unnecessarily due to failure to effectively mobilise traditional supporters and engage the young.

The same could be said for Machap Jaya where Ginie Lim Siew Lin was dropped as a candidate. Party factionalism and Anwar’s poor party leadership played a role in PKR’s Malacca defeat.

Of all the Harapan parties that lost support, it was the DAP that lost the largest share of the popular vote, 5 percent. This is due in part to the fact that the number of voters in its more urban seats is higher.

Nevertheless, slim margins in Gadek, Bemban and Pengkalan Batu were tied to weaknesses in the party getting out its own base and lack of local familiarity with the candidates in the last two seats.

PN effectively also played the race-card in Gadek and Bemban, pulling Malay support and dividing non-Malays. In some seats such as Ayer Keroh which Kerk Chee Yee won handsomely with a 11,494 majority, challengers also won large shares of the vote, speaking to a need to strengthen connectivity with the ground.

Yet the party faced a particular problem – dissatisfaction with the memorandum of understanding (MOU) and party elite deals with the current government among its traditional political base.

Some traditional DAP voters in these areas angrily spoke of the party’s support for the race-based marginalisation in the budget. Its support of the Chinese voters who voted only dropped marginally, by an estimated 2 percent.

Harapan lost most support among Malay and Indian communities, estimated at 14 percent and 22 percent respectively.

While my future microanalysis will explore this further, the main dynamic appears to be the effective use of resources by opponents, who capitalised on those voters economically struggling in the Covid pandemic.

That they opted for financial rewards on offer, security, shows that Covid conditions did shape the campaign. It also reveals that Harapan did not properly address the economic concerns of those who voted for them in GE14.

Bersatu bonanza

The biggest electoral winner in terms of overall support was Bersatu, gaining 6 percent in vote share to 15 percent overall. This was concentrated among Malays but extended across communities, as shown in Table 2.

Malay support for PN, which Bersatu anchored, rose estimated at 17 percent. Interviews suggest this support was concentrated among younger voters, many of whom felt the party offered them the opportunity and greater financial security.

Bersatu established itself in its voter engagement and is building a political base that positions the party well when more younger voters are finally enfranchised.

In looking at the two seats Bersatu won – Bemban and Sungai Udang. These were close races, with majorities of 328 and 530 respectively. In both cases, the police/military vote appears to have advantaged Bersatu.

If Bersatu made a mistake in the campaign, it was announcing its chief minister candidate Mas Ermieyati Samsudin too late in the campaign period.

What then do these results tell us?

On the one hand, new parties are competitive and the electorate is opting for new choices, looking and hoping for better governance and security.

On the other hand, the lack of participation in the election is worrying, as it reflects weak parties and growing dissatisfaction with the options on offer, especially among Malaysia’s minorities.

The key will be whether parties and coalitions learn the lessons from these results.

BRIDGET WELSH is a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. She currently is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. She tweets at @dririshsea.

PKR lost only a small share of the vote, from 10 percent to 9 percent in its wiped-out seat losses. If either party had pulled home more of its supporters it would have been able to secure more victories.

Interviews in the field showed that PKR hurt itself. Of all the parties in Harapan, PKR’s machinery was the weakest, most fractured on the ground. Some of its own party members stayed home.

Paya Rumput, where Shamsul Iskandar contested was ripe for victory with large numbers of young voters, was lost unnecessarily due to failure to effectively mobilise traditional supporters and engage the young.

The same could be said for Machap Jaya where Ginie Lim Siew Lin was dropped as a candidate. Party factionalism and Anwar’s poor party leadership played a role in PKR’s Malacca defeat.

Of all the Harapan parties that lost support, it was the DAP that lost the largest share of the popular vote, 5 percent. This is due in part to the fact that the number of voters in its more urban seats is higher.

Nevertheless, slim margins in Gadek, Bemban and Pengkalan Batu were tied to weaknesses in the party getting out its own base and lack of local familiarity with the candidates in the last two seats.

PN effectively also played the race-card in Gadek and Bemban, pulling Malay support and dividing non-Malays. In some seats such as Ayer Keroh which Kerk Chee Yee won handsomely with a 11,494 majority, challengers also won large shares of the vote, speaking to a need to strengthen connectivity with the ground.

Yet the party faced a particular problem – dissatisfaction with the memorandum of understanding (MOU) and party elite deals with the current government among its traditional political base.

Some traditional DAP voters in these areas angrily spoke of the party’s support for the race-based marginalisation in the budget. Its support of the Chinese voters who voted only dropped marginally, by an estimated 2 percent.

Harapan lost most support among Malay and Indian communities, estimated at 14 percent and 22 percent respectively.

While my future microanalysis will explore this further, the main dynamic appears to be the effective use of resources by opponents, who capitalised on those voters economically struggling in the Covid pandemic.

That they opted for financial rewards on offer, security, shows that Covid conditions did shape the campaign. It also reveals that Harapan did not properly address the economic concerns of those who voted for them in GE14.

Bersatu bonanza

The biggest electoral winner in terms of overall support was Bersatu, gaining 6 percent in vote share to 15 percent overall. This was concentrated among Malays but extended across communities, as shown in Table 2.

Malay support for PN, which Bersatu anchored, rose estimated at 17 percent. Interviews suggest this support was concentrated among younger voters, many of whom felt the party offered them the opportunity and greater financial security.

Bersatu established itself in its voter engagement and is building a political base that positions the party well when more younger voters are finally enfranchised.

In looking at the two seats Bersatu won – Bemban and Sungai Udang. These were close races, with majorities of 328 and 530 respectively. In both cases, the police/military vote appears to have advantaged Bersatu.

If Bersatu made a mistake in the campaign, it was announcing its chief minister candidate Mas Ermieyati Samsudin too late in the campaign period.

What then do these results tell us?

On the one hand, new parties are competitive and the electorate is opting for new choices, looking and hoping for better governance and security.

On the other hand, the lack of participation in the election is worrying, as it reflects weak parties and growing dissatisfaction with the options on offer, especially among Malaysia’s minorities.

The key will be whether parties and coalitions learn the lessons from these results.

BRIDGET WELSH is a senior research associate at the Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies and a senior associate fellow of The Habibie Centre. She currently is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (Unari) based in Kuala Lumpur. She tweets at @dririshsea.

STUPID HARAPAN JUST MAKE SURE IN SARAWAK PKR GETS 5 Seat ALLOCATION ONLY AND START REDUCING THEIR NATIONAL TAKE BY 70% IF YOU WANT TO WIN GE15 AT STATE LEVEL WITH HARAPAN TO SACK MALAYA AT ANY TIME WITH 2/3 MAJORITY!!...CHANGE STATE CONSTITUTION...ABOLISH ALL THOSE KHAT SUPREMACIST RUBBISH WHILE PROMOTING THEM IN THE SPIRIT OF ISLAM HUDAYBIYYAH ideology...wink wink...nudge nudge

ReplyDelete