Remembering the Armenian link in Penang: Restoration of Armenian graves in the Western Road Cemetery

The newly cleaned Armenians’ combined plot at Western Road Cemetery. — Picture by Opalyn Mok

Sunday, 28 Apr 2024 7:00 AM MYT

GEORGE TOWN, April 28 — More than 220 years ago, Armenian traders and merchants landed in Penang, creating a trading link between India, Singapore and Penang.

One of the earliest records of the Armenians settling down in Penang is a house title deed dated 1801 with the name “The Armenian House” referring to a house at the junction of Beach Street and Armenian Street.

This piece of information can be found in a book titled The Armenians of Penang by Nadia Wright.

It is believed the road where the house was located was subsequently named Armenian Lane, as noted in an old map dated 1807.

According to Wright, most of the Armenians in Penang came from Persia as early as 1800 with others from India, right after the British “acquired” Penang.

Though the Armenians were a minority at the time, with less than 180 in number over a 150-year period, they played a significant role in Penang’s economic and civil life.

Among the well-known Armenian personalities at that time was the doyen of the Armenian community, Catchatoor Galastaun, who funded the Armenian Church; the Sarkies brothers who established the E&O Hotel, the Anthony family who were the founders of stockbroking firm, A.A. Anthony & Co; Dr Thaddeus Avetoom of the Georgetown Dispensary; the Ipekdjians who were jewellers and the Gregorys.

Sunday, 28 Apr 2024 7:00 AM MYT

GEORGE TOWN, April 28 — More than 220 years ago, Armenian traders and merchants landed in Penang, creating a trading link between India, Singapore and Penang.

One of the earliest records of the Armenians settling down in Penang is a house title deed dated 1801 with the name “The Armenian House” referring to a house at the junction of Beach Street and Armenian Street.

This piece of information can be found in a book titled The Armenians of Penang by Nadia Wright.

It is believed the road where the house was located was subsequently named Armenian Lane, as noted in an old map dated 1807.

According to Wright, most of the Armenians in Penang came from Persia as early as 1800 with others from India, right after the British “acquired” Penang.

Though the Armenians were a minority at the time, with less than 180 in number over a 150-year period, they played a significant role in Penang’s economic and civil life.

Among the well-known Armenian personalities at that time was the doyen of the Armenian community, Catchatoor Galastaun, who funded the Armenian Church; the Sarkies brothers who established the E&O Hotel, the Anthony family who were the founders of stockbroking firm, A.A. Anthony & Co; Dr Thaddeus Avetoom of the Georgetown Dispensary; the Ipekdjians who were jewellers and the Gregorys.

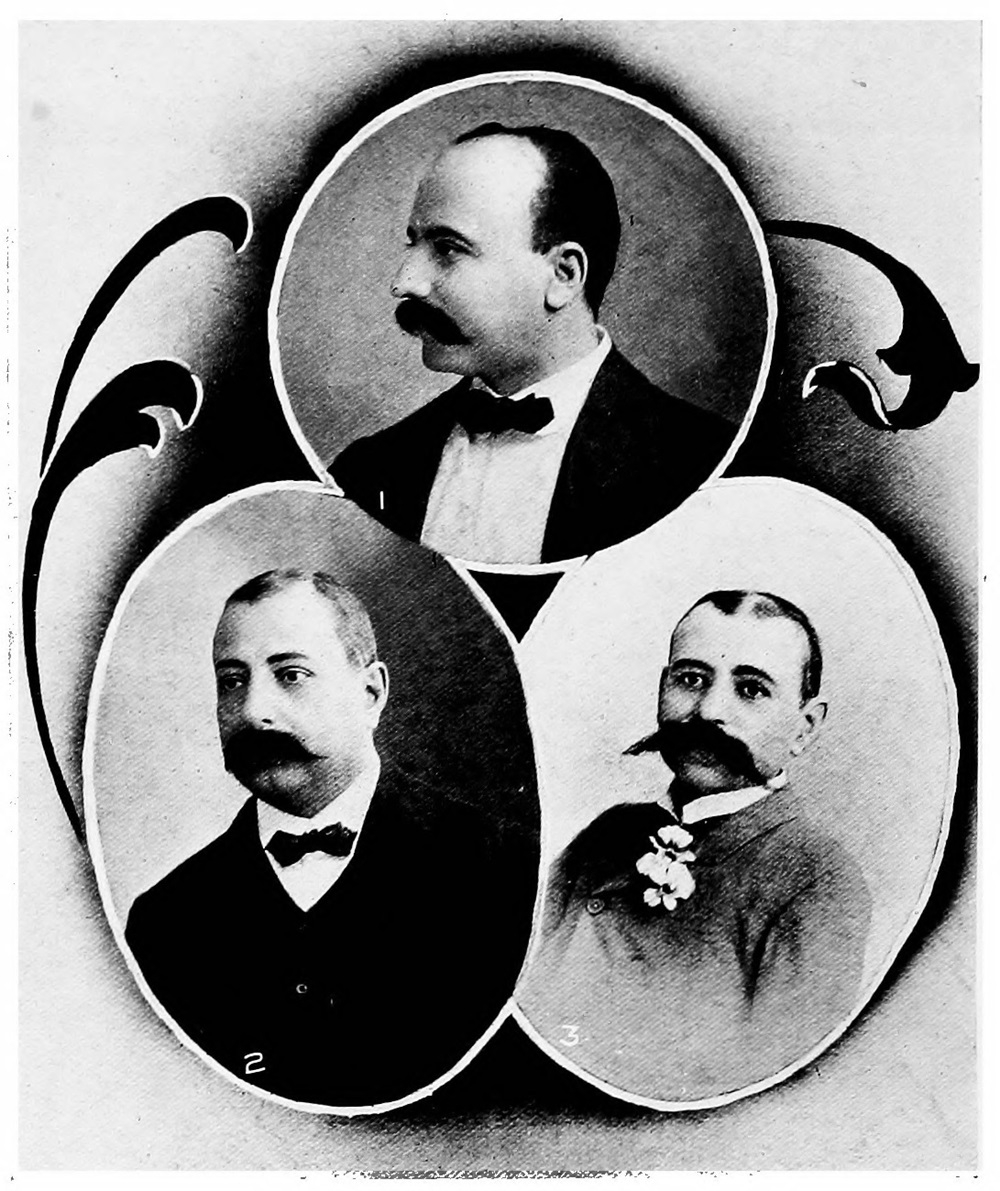

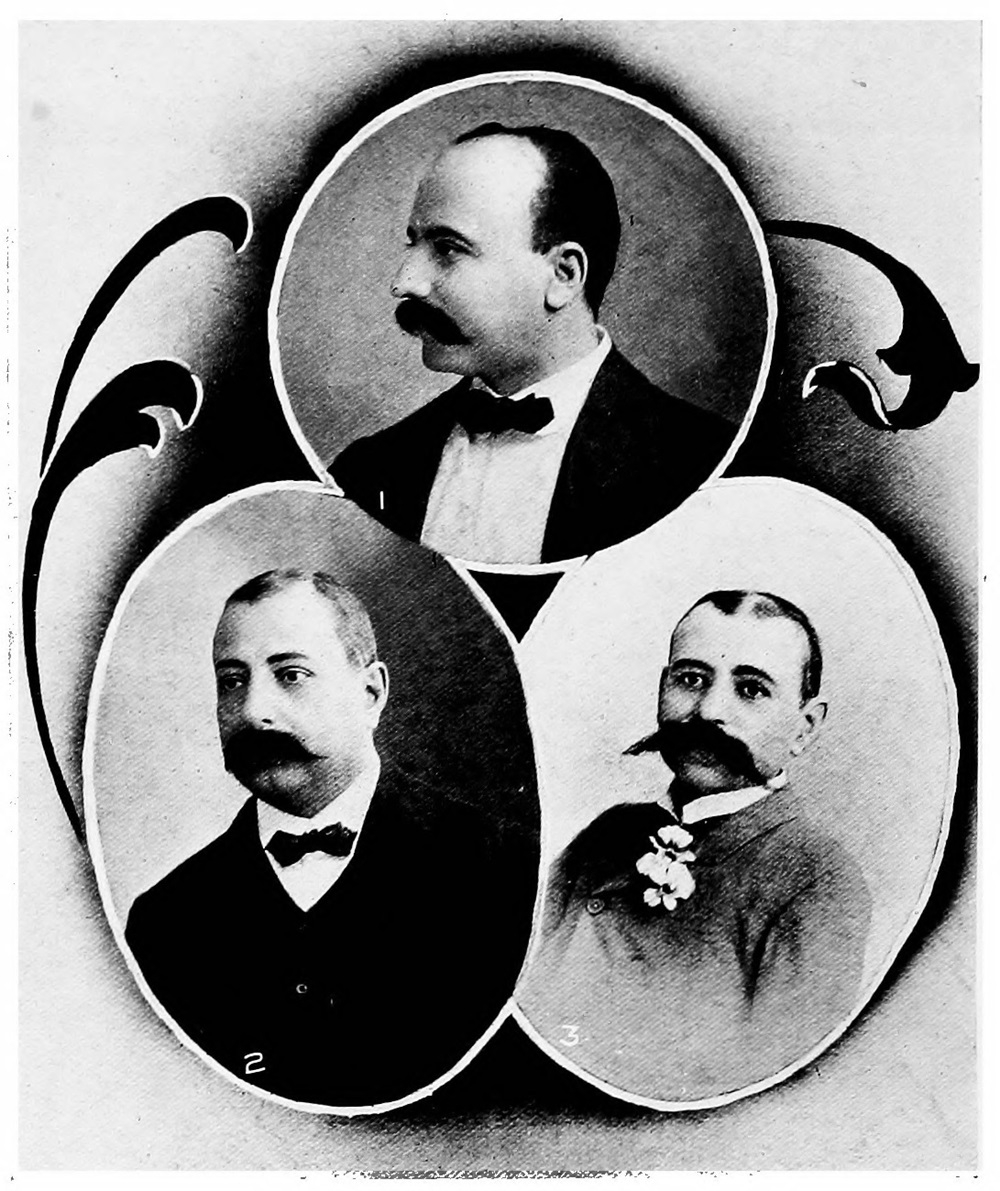

Three of the Sarkies brothers, Arshak (top), Aviet (left) and Tigran (right). — From Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya

The Armenian community in Penang dwindled eventually as they left for Singapore and other countries.

E&O Hotel and A.A. Anthony & Co remained as reminders of their presence here, along with the few graves of Armenian personalities in Western Road Cemetery and the Northam Road Old Protestant Cemetery.

The remains of 20 Armenian merchants, including six from the Anthony family, were buried in a combined plot at the Western Road Cemetery but due to years of neglect, the grave site is overgrown with vegetation and the headstones covered in mould.

Wright, in her book, noted the deplorable conditions of the grave site and appealed for an Armenian benefactor to restore and maintain the site as a reminder of the Armenians link to Penang.

The Armenian community in Penang dwindled eventually as they left for Singapore and other countries.

E&O Hotel and A.A. Anthony & Co remained as reminders of their presence here, along with the few graves of Armenian personalities in Western Road Cemetery and the Northam Road Old Protestant Cemetery.

The remains of 20 Armenian merchants, including six from the Anthony family, were buried in a combined plot at the Western Road Cemetery but due to years of neglect, the grave site is overgrown with vegetation and the headstones covered in mould.

Wright, in her book, noted the deplorable conditions of the grave site and appealed for an Armenian benefactor to restore and maintain the site as a reminder of the Armenians link to Penang.

Cleaning works at the Armenians’ combined plot at Western Road Cemetery. — Picture courtesy of Marcus Langdon

This caught the attention of Mrs Kohar Khatchadourian and the Kohar Ensemble which then led to a five-year effort to restore the grave site starting from 2019.

The Kohar Ensemble, a symphony and orchestra in Armenia, contacted Penang-based historian Marcus Langdon and he became the co-ordinator for the restoration efforts.

The headstones at the communal plot were cleaned and some of the names were painted at the start of the restoration efforts in 2019 but everything came to a halt during the Covid-19 pandemic.

This caught the attention of Mrs Kohar Khatchadourian and the Kohar Ensemble which then led to a five-year effort to restore the grave site starting from 2019.

The Kohar Ensemble, a symphony and orchestra in Armenia, contacted Penang-based historian Marcus Langdon and he became the co-ordinator for the restoration efforts.

The headstones at the communal plot were cleaned and some of the names were painted at the start of the restoration efforts in 2019 but everything came to a halt during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Repainting the wordings on the Armenian headstones at the combined plot in Western Road Cemetery. — Picture courtesy of Marcus Langdon

Finally, early this month, the Kohar Ensemble sent an employee, Serena Vartabedian, to Penang to supervise restoration efforts for the grave site that has 12 headstones.

Vartabedian said the grave site was in bad condition again after more than four years since they started restoration works, with most of the wordings on the headstones faded away.

“I have to be here to trace out the carved words to make out the names that were written in Armenian,” she said.

It took about two weeks to clean up the grave site and headstones and repaint the names.

Finally, early this month, the Kohar Ensemble sent an employee, Serena Vartabedian, to Penang to supervise restoration efforts for the grave site that has 12 headstones.

Vartabedian said the grave site was in bad condition again after more than four years since they started restoration works, with most of the wordings on the headstones faded away.

“I have to be here to trace out the carved words to make out the names that were written in Armenian,” she said.

It took about two weeks to clean up the grave site and headstones and repaint the names.

A new grave stone was made at Arshak Sarkies’ grave at the Western Road Cemetery. — Picture by Opalyn Mok

Arshak Sarkies’ grave, which is nearby, was also cleaned and a new gravestone made.

Arshak Sarkies was one of the Sarkies brothers who established E&O Hotel. The youngest of the four Sarkies brothers, he managed the E&O Hotel for almost four decades before he died in 1931.

As for the combined gravesite, though the remains of 20 Armenians were interred there, only 12 headstones survived while there are no traces of the identities of the remaining eight Armenians.

The 20 Armenians were initially buried in the church graveyard or the church aisle of the Armenian Apostolic Church of St Gregory the Illuminator on Bishop Street.

The church was consecrated in 1824 but a portion of it collapsed in February 1909 before it was eventually demolished in the same year.

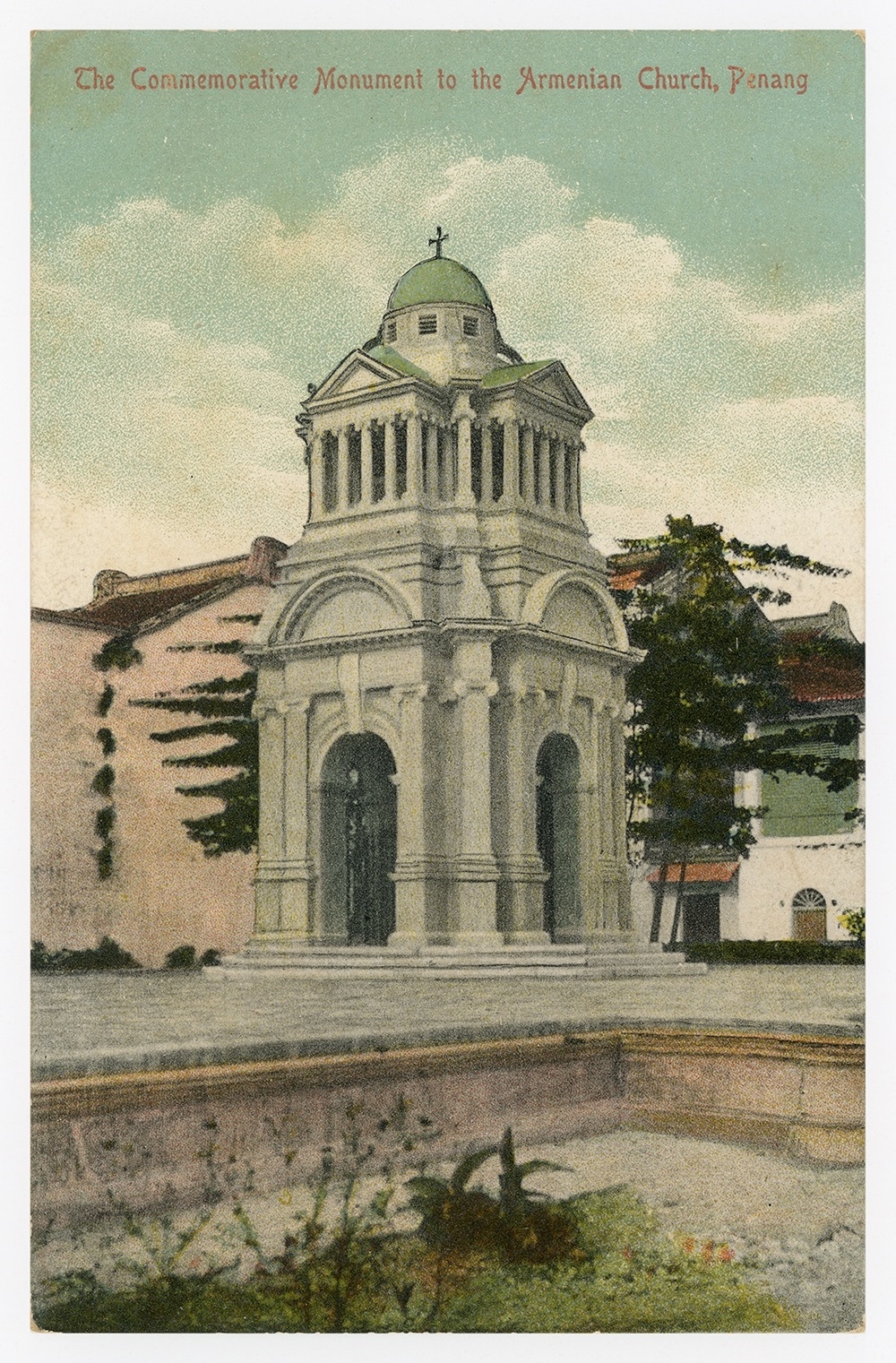

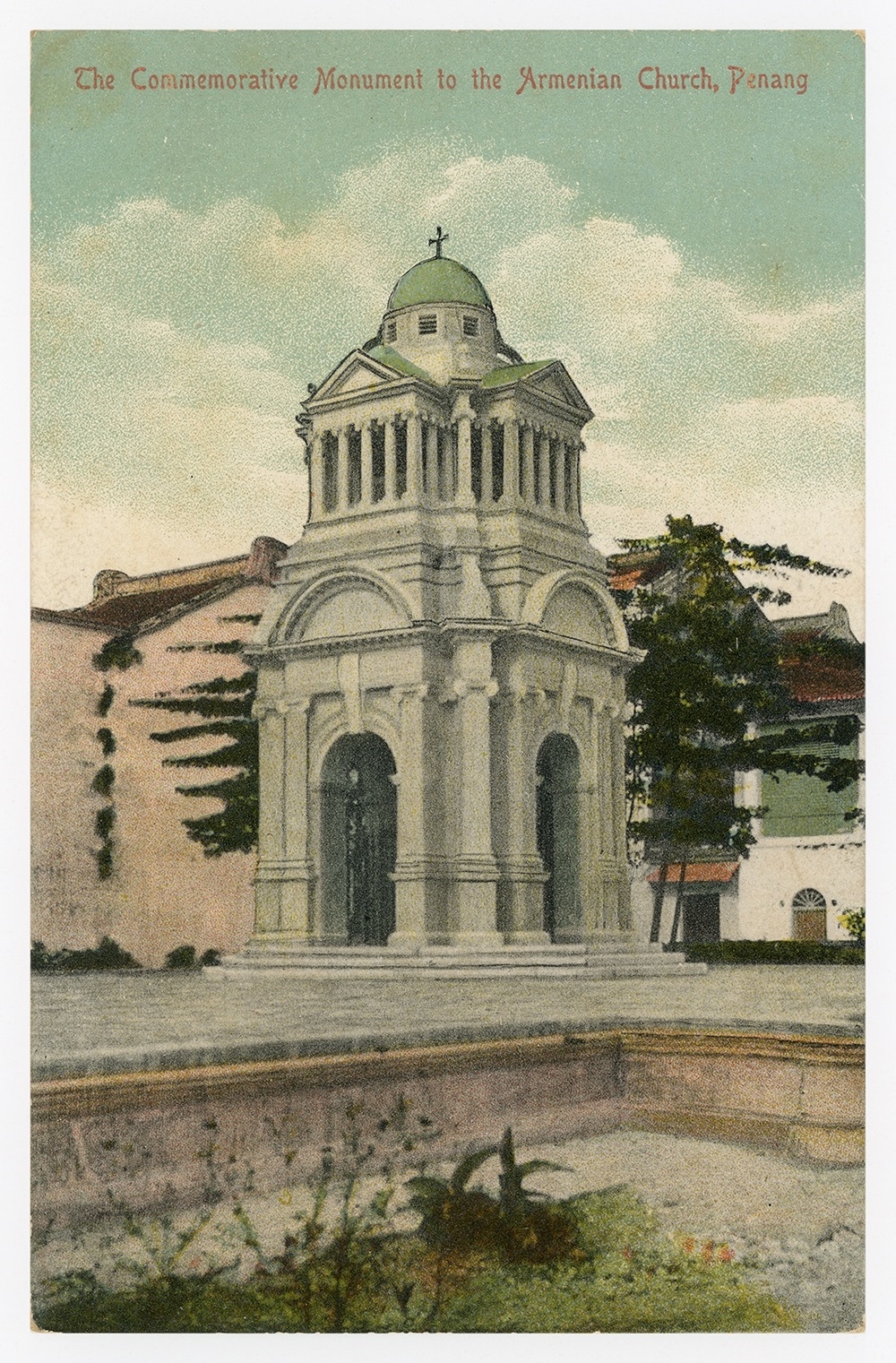

According to Wright, Joseph Anthony and Arshak Sarkies commissioned Henry Neubronner to design a monument to commemorate the church.

Arshak Sarkies’ grave, which is nearby, was also cleaned and a new gravestone made.

Arshak Sarkies was one of the Sarkies brothers who established E&O Hotel. The youngest of the four Sarkies brothers, he managed the E&O Hotel for almost four decades before he died in 1931.

As for the combined gravesite, though the remains of 20 Armenians were interred there, only 12 headstones survived while there are no traces of the identities of the remaining eight Armenians.

The 20 Armenians were initially buried in the church graveyard or the church aisle of the Armenian Apostolic Church of St Gregory the Illuminator on Bishop Street.

The church was consecrated in 1824 but a portion of it collapsed in February 1909 before it was eventually demolished in the same year.

According to Wright, Joseph Anthony and Arshak Sarkies commissioned Henry Neubronner to design a monument to commemorate the church.

The Armenian Monument circa 1910. — Postcard image courtesy of Marcus Langdon

The monument was built at the corner of Bishop and King Streets but as the Armenian community dwindled, the monument fell into disrepair and it was demolished in the 1930s.

The remains of the 20 Armenians along with the 12 surviving headstones were then reinterred in the Western Road Cemetery in August 1937.

Vartabedian said the Armenians reinterred in the combined plot were mostly from well-known Armenian families.

Most notably, three generations of the Anthony family are buried there. This includes the patriarch Arratoon Anthony, his wife Vartkhatoon Anthony, son Anthony Arratoon Anthony and grandchildren, Sophia, Hyrapiet and Alexander.

Arratoon and Vartkhatoon Anthony arrived in Penang with their three sons, Anthony, Satoor and Johannes in 1819.

The monument was built at the corner of Bishop and King Streets but as the Armenian community dwindled, the monument fell into disrepair and it was demolished in the 1930s.

The remains of the 20 Armenians along with the 12 surviving headstones were then reinterred in the Western Road Cemetery in August 1937.

Vartabedian said the Armenians reinterred in the combined plot were mostly from well-known Armenian families.

Most notably, three generations of the Anthony family are buried there. This includes the patriarch Arratoon Anthony, his wife Vartkhatoon Anthony, son Anthony Arratoon Anthony and grandchildren, Sophia, Hyrapiet and Alexander.

Arratoon and Vartkhatoon Anthony arrived in Penang with their three sons, Anthony, Satoor and Johannes in 1819.

The newly cleaned combined grave site of the Armenians at the Western Road Cemetery with Arratoon Anthony’s headstone at the front. — Picture by Opalyn Mok

They lived in Clove Hall. Incidentally, Arratoon Road, which is next to Clove Hall Road, was named after Arratoon Anthony.

Anthony, Satoor and Johannes set up businesses of their own in Penang between the 1860s and 1870s but Anthony outshone his brothers when he set up A.A. Anthony & Co in 1840 as an importer and exporter.

A.A. Anthony & Co remains in existence till today as a stockbroking firm although it is no longer owned by the Anthony family.

A.A. Anthony died in 1873 and was buried in one of the aisles of St Gregory’s Church before his remains, along with his three children and parents, were reinterred in Western Road Cemetery.

The wife of Catchatoor Galastaun, Varterny (spelled as Vardiny on the headstone), was also among the 20 Armenians buried in the combined plot.

Catchatoor Galastaun was a prominent Armenian businessman who funded the construction of St Gregory’s Church and married Varterny Carapiet in the church right after it was consecrated in 1824.

The remaining Armenians in the combined plot are Markar Carapiet; Joseph Gregory Lucas; Tateos Haroutyounian; Kavork Arratoon; Mackertich Kohanness Carapiet; Catherine, the wife of Stuart Herriot, and Hyrapiet Ter Garbirel.

Khatchadourian and the Kohar Ensemble sponsored the full restoration and cleaning of the combined grave site and Arshak Sarkies’ grave.

Vartabedian said Khatchadourian and Kohar Ensemble have also engaged a local contractor to conduct regular maintenance and cleaning of the gravesite twice a year.

They lived in Clove Hall. Incidentally, Arratoon Road, which is next to Clove Hall Road, was named after Arratoon Anthony.

Anthony, Satoor and Johannes set up businesses of their own in Penang between the 1860s and 1870s but Anthony outshone his brothers when he set up A.A. Anthony & Co in 1840 as an importer and exporter.

A.A. Anthony & Co remains in existence till today as a stockbroking firm although it is no longer owned by the Anthony family.

A.A. Anthony died in 1873 and was buried in one of the aisles of St Gregory’s Church before his remains, along with his three children and parents, were reinterred in Western Road Cemetery.

The wife of Catchatoor Galastaun, Varterny (spelled as Vardiny on the headstone), was also among the 20 Armenians buried in the combined plot.

Catchatoor Galastaun was a prominent Armenian businessman who funded the construction of St Gregory’s Church and married Varterny Carapiet in the church right after it was consecrated in 1824.

The remaining Armenians in the combined plot are Markar Carapiet; Joseph Gregory Lucas; Tateos Haroutyounian; Kavork Arratoon; Mackertich Kohanness Carapiet; Catherine, the wife of Stuart Herriot, and Hyrapiet Ter Garbirel.

Khatchadourian and the Kohar Ensemble sponsored the full restoration and cleaning of the combined grave site and Arshak Sarkies’ grave.

Vartabedian said Khatchadourian and Kohar Ensemble have also engaged a local contractor to conduct regular maintenance and cleaning of the gravesite twice a year.

The Armenian community , just like the Jewish community , in Penang has disappeared into history.

ReplyDeleteThe descendants married into the Chinese, Indian or Malay community , or their descendants have moved overseas.

It is dangerous for any Malaysian citizen with an obvious Jewish surname to reside in Malaysia. The ones I knew in my childhood all moved to Australia, UK or Singapore, never to return .

The one I knew, no one knew he was Jewish, not even his colleagues, not even me. They thought he was Muslim because whenever they went out for lunch, he'd only eat nasi kandar. I only found out when he told me one day. Up until then I thought he was a Chinese because of his fluency in Hokkien. He has since moved to Australia. Jewish surnames sound like German surnames sometimes. I doubt Malaysians are smart enough to tell who's Jew and who's not.

ReplyDelete"Ashkenazi Jews didn’t have surnames until the 18th century, when they were required by law for the first time to register their names with the non-Jewish state. Since they were already using patronymics and matronymics, most people took on Yiddish/Germanic or Slavic versions of the names they were already using.

"Someone named Weiss might be Jewish, but since that’s just a German word meaning “white”, it’s no real indicator that the person with that name is Jewish."