Mandatory History in Malaysia: Whose Truth Will Your Children Learn?

29 Jan 2026 • 10:00 AM MYT

TheRealNehruism

An award-winning Newswav creator, Bebas News columnist & ex-FMT columnist

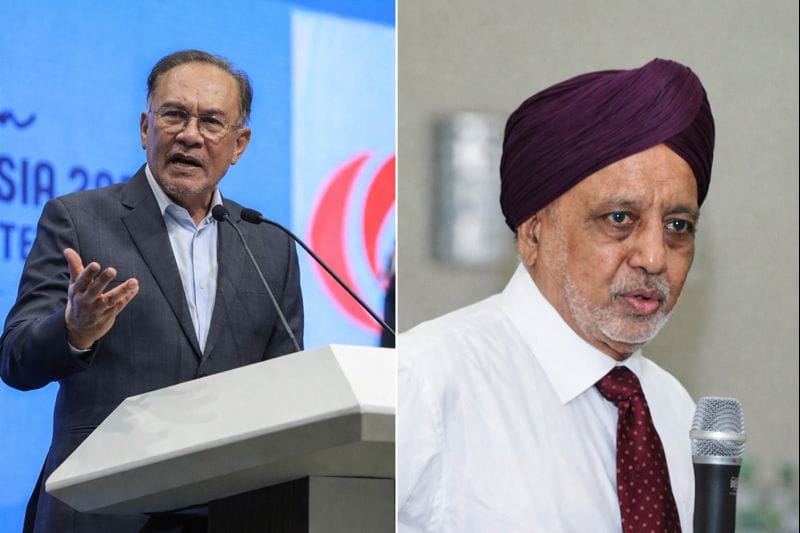

When unveiling his National Education Plan last week, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim announced that History will be made a mandatory subject for all Malaysian students in all schools, including private, international, religious institutions, and those offering the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC).

At this stage, it is still unclear how this policy will play out in practice. But I suspect it may soon become fodder for renewed racial tension, because the teaching of history in Malaysia is already a deeply contentious issue.

Malaysians, as are well aware of, are most capable of conjuring up racially tinged outrages over anything.

The Indian have a saying, “if you are champion, even a blade of grass can become your weapon.” Following that logic, Malaysia certainly does not lack race champions, who can turn everything from a sandwich to a flag to pig farming, into a way to fuel racial tension by some other means.

A few years ago, there was already an outcry that Malaysian history was being rewritten to suit Malay sensibilities.

lthough it is not often said out loud, it is an open secret that one of the main reasons that other streams of school exists is because other races would prefer having their children taught according to their own sensibilities, not the Malay sensibilities.

Considering that, I don't see how teaching Malaysian history, which is most likely going to be written following the Malay sensibility, in schools that are created so that children don't have to be molded following the Malay sensibilities, is not going to cause an issue.

Now some people might claim that this entire issue can be avoided all together if we all just stick to the truth instead of sensibilities, but to this I will argue that history is always written according to sensibilities, not truth.

There is a reason why we often say that history is written by the victors. Victors do not merely record events; they justify their victory, sanctify their actions, and moralise their dominance. This is not a uniquely Malaysian phenomenon. It is a universal one, observable across time and civilisation.

We often comfort ourselves with the belief that history exists as an objective, absolute record of facts—facts that will be interpreted the same way regardless of who reads them. That belief has never been true.

Some historical claims, for example, are patently and self evidently false. Yet the influence of power over historical narratives is so overwhelming that even when falsehoods are plainly visible, they continue to be widely accepted as truth.

Take a simple example: Christopher Columbus did not discover America. There were already people living there when he arrived. And yet, generations have been taught otherwise. The persistence of this lie has nothing to do with evidence, and everything to do with who had the power to define the story.

Or consider World War II. It is commonly framed as a battle between good and evil. In reality, it was largely a struggle between supremacist, exploitative and parasitical colonial powers over who had the right to dominate the world on racial and imperial terms.

Hitler and Nazi Germany were not fundamentally different from European colonial powers such as the British, French, Dutch, or Belgians. The atrocities committed by Nazi Germany in occupied territories were not categorically more severe or morally distinct from the atrocities committed by those same Allied powers in the lands they colonised.

Yet Hitler and the Nazis are remembered as uniquely evil. Why? Not because their crimes were unprecedented—but because they lost, and the winners wrote history in a way that cast themselves as moral saviours rather than competing oppressors.

Even our understanding of who defeated the Axis powers is shaped by power rather than fact. The greatest sacrifices and most decisive blows against Nazi Germany were delivered by the Soviet Union. Similarly, it was China—both Nationalist and Communist—that bore the brunt of Japan’s imperial aggression.

And yet, popular history overwhelmingly credits the United States and its Western allies as the primary victors of World War II. This is not because the facts support it, but because the Soviet and Chinese Communists lost the Cold War—and history was rewritten accordingly.

I could go on. But the point should already be clear.

What we call “historical fact” is often less about truth and more about identity, power, and dominance. History is not merely a record of what happened; it is a narrative shaped by those who prevailed, designed to legitimise themselves and delegitimise those who did not.

So when we argue today about history being rewritten, we should at least be honest about one thing:

history has never been neutral to begin with.

This is not a theoretical concern. Malaysia already has a documented history of how state power shapes historical narratives.

Several years ago, historian Ranjit Singh Malhi publicly criticised the content of secondary school history textbooks used from Form 1 to Form 5, describing them as biased, inaccurate, and selectively constructed. According to him, these textbooks omitted key facts relevant to nation-building while including distortions and exaggerations that served a particular ideological purpose.

His core criticism was simple but damning: Malaysian students were being taught history largely from the perspective of a single ethnic group. The textbooks, he argued, were skewed towards establishing Islamic and Malay dominance, rather than presenting a balanced and inclusive account of the emergence of Malaysia as a plural society.

The consequences of this bias were not subtle. The economic and infrastructural contributions of the Malaysian Chinese and Indian communities—particularly the role of Chinese enterprise in tin mining and Indian labour in the rubber industry—were reduced to a handful of sentences. The histories of Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia and Orang Asal communities in Sabah and Sarawak were similarly marginalised.

More strikingly, the textbooks failed to adequately acknowledge the profound Hindu-Buddhist influence on early Malay civilisation. Concepts such as devaraja—the Hindu idea of the god-king that shaped early Malay kingship—were either downplayed or ignored altogether, despite their clear historical significance. The impact of Indian civilisation on Malay language, governance, literature, and court culture was treated as peripheral rather than foundational.

At the same time, Islamic civilisation was given disproportionate emphasis. Topics on Indian and Chinese civilisations were covered in fewer than ten pages each, while Islamic civilisation alone occupied more than twenty pages. This imbalance was not accidental; it reflected a conscious choice about which civilisational strands were to be foregrounded and which were to be treated as footnotes..

In other words, what students were being taught was not simply history, but a carefully curated narrative —one that naturalises the Malay version of event, as a historical fact, rather than political doctrine, even if it diminishes the non-Malays identity, existence and contributions.

Seen in this light, the decision to make History compulsory across all schools does not take place on neutral ground. It builds upon an existing framework where the state already exercises significant control over historical interpretation. Making such a subject mandatory across every educational stream—including private, international, and UEC schools—only amplifies the power of that framework.

And this returns us to the central issue.

History is never just about the past. It is about who gets to define belonging in the present, and who must adapt, assimilate, or disappear into the margins of the national story.

So the question Malaysia now faces is not whether History should be taught to all students. Every nation does that.

The real question is far more uncomfortable:

Whose history will be taught—and whose will be forgotten?

At this stage, it is still unclear how this policy will play out in practice. But I suspect it may soon become fodder for renewed racial tension, because the teaching of history in Malaysia is already a deeply contentious issue.

Malaysians, as are well aware of, are most capable of conjuring up racially tinged outrages over anything.

The Indian have a saying, “if you are champion, even a blade of grass can become your weapon.” Following that logic, Malaysia certainly does not lack race champions, who can turn everything from a sandwich to a flag to pig farming, into a way to fuel racial tension by some other means.

A few years ago, there was already an outcry that Malaysian history was being rewritten to suit Malay sensibilities.

lthough it is not often said out loud, it is an open secret that one of the main reasons that other streams of school exists is because other races would prefer having their children taught according to their own sensibilities, not the Malay sensibilities.

Considering that, I don't see how teaching Malaysian history, which is most likely going to be written following the Malay sensibility, in schools that are created so that children don't have to be molded following the Malay sensibilities, is not going to cause an issue.

Now some people might claim that this entire issue can be avoided all together if we all just stick to the truth instead of sensibilities, but to this I will argue that history is always written according to sensibilities, not truth.

There is a reason why we often say that history is written by the victors. Victors do not merely record events; they justify their victory, sanctify their actions, and moralise their dominance. This is not a uniquely Malaysian phenomenon. It is a universal one, observable across time and civilisation.

We often comfort ourselves with the belief that history exists as an objective, absolute record of facts—facts that will be interpreted the same way regardless of who reads them. That belief has never been true.

Some historical claims, for example, are patently and self evidently false. Yet the influence of power over historical narratives is so overwhelming that even when falsehoods are plainly visible, they continue to be widely accepted as truth.

Take a simple example: Christopher Columbus did not discover America. There were already people living there when he arrived. And yet, generations have been taught otherwise. The persistence of this lie has nothing to do with evidence, and everything to do with who had the power to define the story.

Or consider World War II. It is commonly framed as a battle between good and evil. In reality, it was largely a struggle between supremacist, exploitative and parasitical colonial powers over who had the right to dominate the world on racial and imperial terms.

Hitler and Nazi Germany were not fundamentally different from European colonial powers such as the British, French, Dutch, or Belgians. The atrocities committed by Nazi Germany in occupied territories were not categorically more severe or morally distinct from the atrocities committed by those same Allied powers in the lands they colonised.

Yet Hitler and the Nazis are remembered as uniquely evil. Why? Not because their crimes were unprecedented—but because they lost, and the winners wrote history in a way that cast themselves as moral saviours rather than competing oppressors.

Even our understanding of who defeated the Axis powers is shaped by power rather than fact. The greatest sacrifices and most decisive blows against Nazi Germany were delivered by the Soviet Union. Similarly, it was China—both Nationalist and Communist—that bore the brunt of Japan’s imperial aggression.

And yet, popular history overwhelmingly credits the United States and its Western allies as the primary victors of World War II. This is not because the facts support it, but because the Soviet and Chinese Communists lost the Cold War—and history was rewritten accordingly.

I could go on. But the point should already be clear.

What we call “historical fact” is often less about truth and more about identity, power, and dominance. History is not merely a record of what happened; it is a narrative shaped by those who prevailed, designed to legitimise themselves and delegitimise those who did not.

So when we argue today about history being rewritten, we should at least be honest about one thing:

history has never been neutral to begin with.

This is not a theoretical concern. Malaysia already has a documented history of how state power shapes historical narratives.

Several years ago, historian Ranjit Singh Malhi publicly criticised the content of secondary school history textbooks used from Form 1 to Form 5, describing them as biased, inaccurate, and selectively constructed. According to him, these textbooks omitted key facts relevant to nation-building while including distortions and exaggerations that served a particular ideological purpose.

His core criticism was simple but damning: Malaysian students were being taught history largely from the perspective of a single ethnic group. The textbooks, he argued, were skewed towards establishing Islamic and Malay dominance, rather than presenting a balanced and inclusive account of the emergence of Malaysia as a plural society.

The consequences of this bias were not subtle. The economic and infrastructural contributions of the Malaysian Chinese and Indian communities—particularly the role of Chinese enterprise in tin mining and Indian labour in the rubber industry—were reduced to a handful of sentences. The histories of Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia and Orang Asal communities in Sabah and Sarawak were similarly marginalised.

More strikingly, the textbooks failed to adequately acknowledge the profound Hindu-Buddhist influence on early Malay civilisation. Concepts such as devaraja—the Hindu idea of the god-king that shaped early Malay kingship—were either downplayed or ignored altogether, despite their clear historical significance. The impact of Indian civilisation on Malay language, governance, literature, and court culture was treated as peripheral rather than foundational.

At the same time, Islamic civilisation was given disproportionate emphasis. Topics on Indian and Chinese civilisations were covered in fewer than ten pages each, while Islamic civilisation alone occupied more than twenty pages. This imbalance was not accidental; it reflected a conscious choice about which civilisational strands were to be foregrounded and which were to be treated as footnotes..

In other words, what students were being taught was not simply history, but a carefully curated narrative —one that naturalises the Malay version of event, as a historical fact, rather than political doctrine, even if it diminishes the non-Malays identity, existence and contributions.

Seen in this light, the decision to make History compulsory across all schools does not take place on neutral ground. It builds upon an existing framework where the state already exercises significant control over historical interpretation. Making such a subject mandatory across every educational stream—including private, international, and UEC schools—only amplifies the power of that framework.

And this returns us to the central issue.

History is never just about the past. It is about who gets to define belonging in the present, and who must adapt, assimilate, or disappear into the margins of the national story.

So the question Malaysia now faces is not whether History should be taught to all students. Every nation does that.

The real question is far more uncomfortable:

Whose history will be taught—and whose will be forgotten?

***

That's why Prof Kangkong will continue to thrive, and even be lauded

All historical accounts are politicised...regardless which country it is in.

ReplyDelete