‘Private Adam’ who ran amok in 1987 dead

According to media reports, Adam died at Hospital Pulau Pinang in Georgetown, Penang, yesterday. He was 57. — Screen capture via Google Maps

KUALA LUMPUR, March 31 — Former army private Adam Jaafar, or better known as “Private Adam” who ran amok in the Chow Kit area here in 1987, has died.

According to media reports, Adam died at Hospital Pulau Pinang in Georgetown, Penang, yesterday. He was 57.

The Penang native will be buried at Datuk Keramat in the state capital.

In 1987, then a 23-year-old army private, Adam rode into the Chow Kit suburb on a motorcycle with an M16 assault rifle he had stolen from his military base in Ipoh, Perak.

He launched into a shooting spree in the suburb, killing one person and injuring several others.

Adam was charged over the attack but was found to be mentally unsound and placed in psychiatric care.

The incident spawned various conspiracy theories but in a book thirty years after the incident, Adam put his episode down to early childhood trauma and subsequent ragging by his seniors in the army.

*********

SMH (published 11 years ago)

xxxxxx king's corrupt controller

By Hamish McDonald

January 30, 2010

KUALA LUMPUR, March 31 — Former army private Adam Jaafar, or better known as “Private Adam” who ran amok in the Chow Kit area here in 1987, has died.

According to media reports, Adam died at Hospital Pulau Pinang in Georgetown, Penang, yesterday. He was 57.

The Penang native will be buried at Datuk Keramat in the state capital.

In 1987, then a 23-year-old army private, Adam rode into the Chow Kit suburb on a motorcycle with an M16 assault rifle he had stolen from his military base in Ipoh, Perak.

He launched into a shooting spree in the suburb, killing one person and injuring several others.

Adam was charged over the attack but was found to be mentally unsound and placed in psychiatric care.

The incident spawned various conspiracy theories but in a book thirty years after the incident, Adam put his episode down to early childhood trauma and subsequent ragging by his seniors in the army.

*********

SMH (published 11 years ago)

xxxxxx king's corrupt controller

By Hamish McDonald

January 30, 2010

Few of the world's recent kings have had such a muted send-off from their own people as Mahmood Iskandar of Malaysia, who died on January 22, at his palace in Johor, aged 77.

Iskandar was Yang di-Pertuan Agong, or king, between 1984 and 1989 under the country's peculiar monarchy, where the nine traditional Malay sultans take turns as head of state.

An official statement paid tribute to Iskandar's ''priceless contributions during his lifetime''. Obituaries in the tightly controlled press referred obliquely to his ''mercurial'' ways. It was left to Malaysian bloggers - now being hunted down by the powerful political police, the Special Branch - to mention what every Malaysian knows.

In 1987 a caddie at the Cameron Highlands golf club was unwise enough to laugh when Iskandar missed a putt. The king clubbed the man to death. The news was suppressed and at the time all the Malaysian royals had legal immunity.

Since Iskandar's death, more incidents have been exposed: how he would pull over and spray with Mace anyone who overtook his Rolls-Royce; how he chained two policemen in a dog kennel, and other offenders to his dignity were made to do squat jumps; how hotels and clubs around Johor would hide their young female staff away when Johor royals turned up.

Iskandar's weakness inflicted wider damage on his country - just how much is detailed in a new biography of the prime minister in office at the time, Mahathir Mohamad, by the veteran Australian foreign correspondent Barry Wain, a former editor of The Asian Wall Street Journal.

The king's vulnerability to impeachment by a conference of his fellow sultans made him a compliant instrument for one of Mahathir's shabbiest manoeuvres to reinforce his power, in which the independence and international standing of the Malaysian judiciary was sacrificed for political expediency.

Mahathir, a former doctor, had become prime minister in 1981, impatient to whip his countrymen - especially his fellow Malays - into more competitive shape and for Malaysia to stand taller in the world.

''If necessary, he would crucify opponents, sacrifice allies, and tolerate monumental institutional and social abuses to advance his project,'' Wain writes. Methods included use of the Special Branch and its power under the Internal Security Act to detain without trial. By 1987-88, he faced growing division within the core party of the ruling alliance, the United Malays National Organisation. To get rid of his critics, Mahathir engineered the neat trick of getting UMNO declared an illegal organisation, then set up a ''New UMNO'' without them.

In 1988 the case was heading towards adjudication by the Supreme Court. Two weeks before the hearing King Mahmood Iskandar suspended the court's lord president, Mohamed Salleh Abas. A selected panel of judges duly found him guilty of misconduct in a ruling that the London QC Geoffrey Robertson called ''the most despicable document in modern legal history''.

Iskandar later apologised to Salleh for having been ''made use of'' in his dismissal. The judiciary, like the Special Branch, went on to be a tool of the prime minister, culminating 10 years later in the persecution of Anwar Ibrahim, Mahathir's deputy and chosen successor, on fabricated sodomy and corruption charges.

Wain gives chapter and verse of this and many other examples of abuse of power in his book. This has not bothered Mahathir at all, judging from his reaction since publication. He probably thinks it was all justified by his drive to make a big, modern and prosperous Malaysia by 2020.

He is upset by Wain's questioning of Mahathir's success on this latter front. Wain points out that the 6.1 per cent average growth in gross domestic product under Mahathir was actually outshone by the 8 per cent average achieved in the previous decade.

Wain also outlays the colossal waste of nearly $40 billion on projects like the Proton Saga car, the Perwaja steel project, the information technology corridor, the new capital, Purajaya, and the new Kuala Lumpur airport and on rescuing Malaysia's government banks from forays into market-rigging.

Iskandar was Yang di-Pertuan Agong, or king, between 1984 and 1989 under the country's peculiar monarchy, where the nine traditional Malay sultans take turns as head of state.

An official statement paid tribute to Iskandar's ''priceless contributions during his lifetime''. Obituaries in the tightly controlled press referred obliquely to his ''mercurial'' ways. It was left to Malaysian bloggers - now being hunted down by the powerful political police, the Special Branch - to mention what every Malaysian knows.

In 1987 a caddie at the Cameron Highlands golf club was unwise enough to laugh when Iskandar missed a putt. The king clubbed the man to death. The news was suppressed and at the time all the Malaysian royals had legal immunity.

Since Iskandar's death, more incidents have been exposed: how he would pull over and spray with Mace anyone who overtook his Rolls-Royce; how he chained two policemen in a dog kennel, and other offenders to his dignity were made to do squat jumps; how hotels and clubs around Johor would hide their young female staff away when Johor royals turned up.

Iskandar's weakness inflicted wider damage on his country - just how much is detailed in a new biography of the prime minister in office at the time, Mahathir Mohamad, by the veteran Australian foreign correspondent Barry Wain, a former editor of The Asian Wall Street Journal.

The king's vulnerability to impeachment by a conference of his fellow sultans made him a compliant instrument for one of Mahathir's shabbiest manoeuvres to reinforce his power, in which the independence and international standing of the Malaysian judiciary was sacrificed for political expediency.

Mahathir, a former doctor, had become prime minister in 1981, impatient to whip his countrymen - especially his fellow Malays - into more competitive shape and for Malaysia to stand taller in the world.

''If necessary, he would crucify opponents, sacrifice allies, and tolerate monumental institutional and social abuses to advance his project,'' Wain writes. Methods included use of the Special Branch and its power under the Internal Security Act to detain without trial. By 1987-88, he faced growing division within the core party of the ruling alliance, the United Malays National Organisation. To get rid of his critics, Mahathir engineered the neat trick of getting UMNO declared an illegal organisation, then set up a ''New UMNO'' without them.

In 1988 the case was heading towards adjudication by the Supreme Court. Two weeks before the hearing King Mahmood Iskandar suspended the court's lord president, Mohamed Salleh Abas. A selected panel of judges duly found him guilty of misconduct in a ruling that the London QC Geoffrey Robertson called ''the most despicable document in modern legal history''.

Iskandar later apologised to Salleh for having been ''made use of'' in his dismissal. The judiciary, like the Special Branch, went on to be a tool of the prime minister, culminating 10 years later in the persecution of Anwar Ibrahim, Mahathir's deputy and chosen successor, on fabricated sodomy and corruption charges.

Wain gives chapter and verse of this and many other examples of abuse of power in his book. This has not bothered Mahathir at all, judging from his reaction since publication. He probably thinks it was all justified by his drive to make a big, modern and prosperous Malaysia by 2020.

He is upset by Wain's questioning of Mahathir's success on this latter front. Wain points out that the 6.1 per cent average growth in gross domestic product under Mahathir was actually outshone by the 8 per cent average achieved in the previous decade.

Wain also outlays the colossal waste of nearly $40 billion on projects like the Proton Saga car, the Perwaja steel project, the information technology corridor, the new capital, Purajaya, and the new Kuala Lumpur airport and on rescuing Malaysia's government banks from forays into market-rigging.

KHAT mudah lupa

In addition, there was pervasive corruption under Mahathir's privatisation program, dubbed ''piratisation'' by an opposition leader, Lim Kit Siang.

''The winners were almost all well-connected and influential businessmen, or relatives of politicians,'' Wain writes in the biography.

Malaysia's rich endowment of petroleum, minerals, forests and fertile land kept the economy from crashing. More laissez-faire policies, based on resources and light manufacturing (already thriving before Mahathir came to power) might have produced faster growth; and rigorous education, rather than privilege, more Malay progress.

If you want to see Mahathir's monument, go to Kuala Lumpur and have a look around. Show-projects. Insipid newspapers and TV. Mediocre universities. Fear of the Special Branch. Religious tensions. The latest chosen successor as prime minister under a cloud of scandal.

Or read the national accounts and wonder why a country with the world's highest current account surplus proportionate to its GDP - 15.9 per cent, or about $US32 billion - has hardly increased its foreign reserves at all in the past year. That signals a massive capital flight, an underlying fear that Mahathir changed nothing, only made things worse.

+++++++++

Prebet Adam's family apologises to Johor royal family

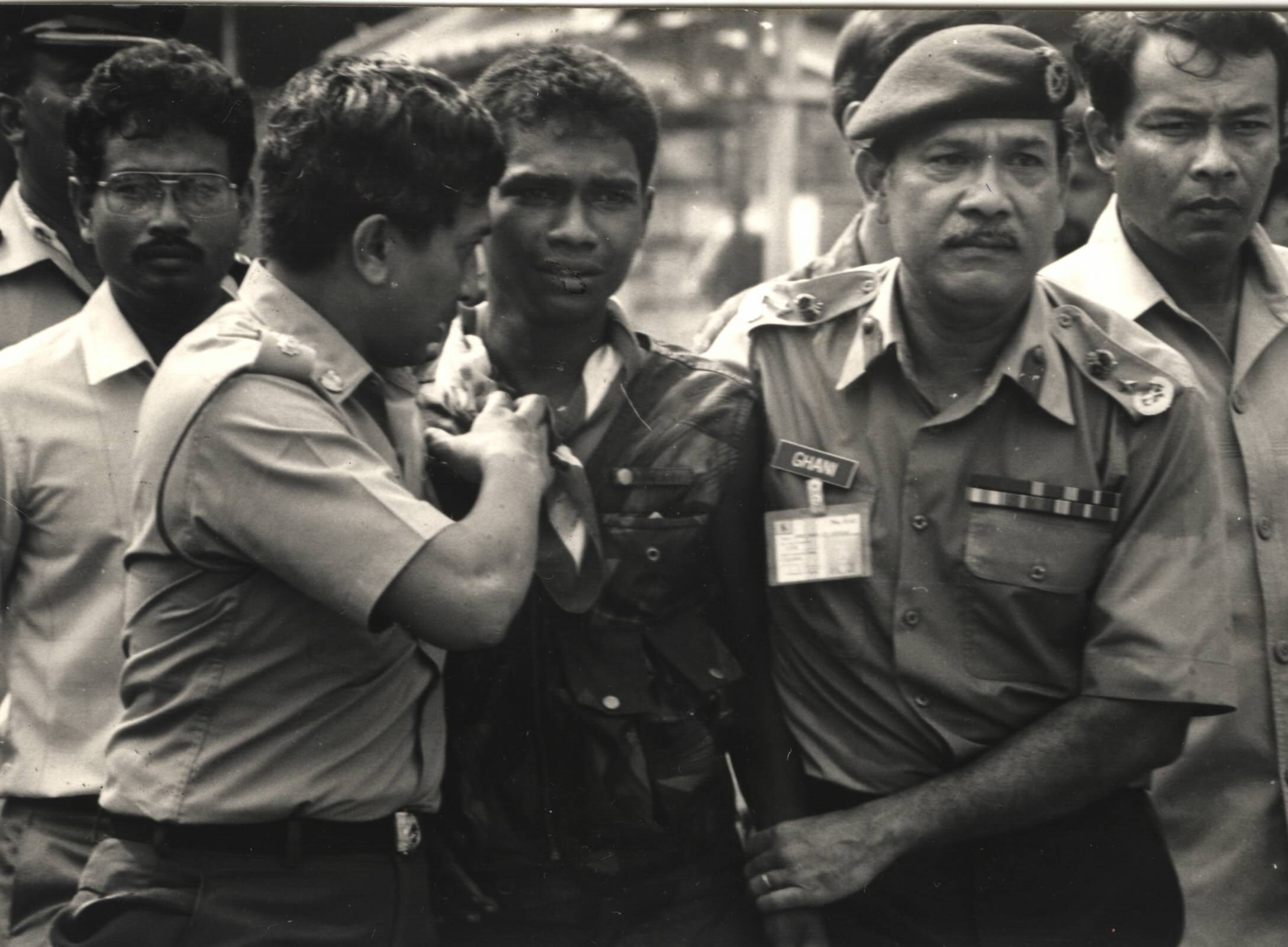

Surrender: Prebet Adam (centre) being led away after his surrender. Scanned Pix : Staric Date : 09.10.1987

PETALING JAYA: The family of Prebet Adam Jaafar, the soldier who went amok at the Chow Kit area in Kuala Lumpur in 1987, has come out to apologise to the Johor royal family.

Hawa Jaafar, 53, his younger sister, refuted the urban legend that Prebet Adam went on a shooting spree because their brother was killed by Sultan Iskandar Ibni Almarhum Sultan Ismail when he was a golf caddy to the former Johor Ruler at the time.

She said the family had to hold back their shame and anger for 30 years because they were unable to explain the truth to the public and the authorities.

“Adam went amok in Chow Kit due to problems in his workplace and not because our brother was killed by the Sultan.

“I apologise to the family of the Tunku Mahkota Johor (Tunku Ismail Sultan Ibrahim) for being dragged into this slander involving my brother Prebet Adam.

“I want to clarify that there were no deaths involving our siblings due to murder. All of us are still alive except for one who passed away in 1975 in a fire.

“In the name of Allah, there was no murder at all,” she told a press conference at her house in George Town on Thursday, a video of which Malay daily Berita Harian uploaded to its YouTube channel.

The video also shows two other siblings present during the press conference, Arina and Arman. Adam is the eldest of nine siblings.

The urban legend over the Chow Kit incident was that the brother was supposedly a golf caddy who had laughed at Sultan Iskandar when the ruler missed a shot.

The late Sultan had then supposedly hit Adam’s brother on the head with a golf club, causing his death.

On Oct 17, 1987, Adam, then a 23-year-old soldier, stole an M16 rifle and a motorcycle from his army camp in Ipoh.

The army Ranger Regiment sharpshooter then rode to Kuala Lumpur.

The next night, he wrote a message on his hotel room mirror: “A damned night for Adam. Mission: to kill or be killed.”

He left his hotel and went on a shooting spree in the city’s Chow Kit area that left one person dead from a bullet ricochet and several others wounded.

Adam shot at cars and at a petrol station fuel tank that burst into flames. He eventually surrendered and at his trial, his defence lawyer entered a plea of temporary insanity.

At the press conference on Thursday, Hawa said the family does not know any member of the Johor royal family and pleaded with the media to help tell the real story and to inform the Tunku Mahkota Johor of their apology.

“We have been accused of receiving RM10,000 monthly to deny the murder. Just look at my house.

“We are merely commoners and have never received a single cent from anyone to deny this matter.

“I just want to ask for justice for those who have been victims of slander due to this,” said Hawa.

The Prebet Adam controversy resurfaced when Tunku Ismail, the Johor crown prince, shared his views on the country’s political situation in a post on the Johor Southern Tigers Facebook page on Sunday (April 8).

He touched on the story of Prebet Adam, saying that his late grandfather Almarhum Sultan Iskandar was not given a chance to defend himself as royalty did not have the luxury of the Internet, and the mainstream media were controlled by the government of the day.

The Prebet Adam urban legend was also debunked in a book published last May, titled Konfesi Prebet Adam.

Its author Syahril A. Kadir posted on Facebook that he forgave those who made allegations and criticised him for writing the book.

“Some said that I created stories to clear the name of the Almarhum Sultan Johor.

“I was accused of receiving dedak (bribes) and insulted but I accepted it because I know I’m on the right side. Finally, Prebet Adam’s own family has clarified what actually happened,” he wrote.

Syahril’s book was based on interviews with key figures in the case, and includes first person accounts by Adam himself, his lawyer Tan Sri Muhammad Shafee Abdullah, and Leftenan Jeneral (R) Datuk Abdul Ghani Abdullah, the military officer who managed to persuade Adam to surrender.

Hawa Jaafar, 53, his younger sister, refuted the urban legend that Prebet Adam went on a shooting spree because their brother was killed by Sultan Iskandar Ibni Almarhum Sultan Ismail when he was a golf caddy to the former Johor Ruler at the time.

She said the family had to hold back their shame and anger for 30 years because they were unable to explain the truth to the public and the authorities.

“Adam went amok in Chow Kit due to problems in his workplace and not because our brother was killed by the Sultan.

“I apologise to the family of the Tunku Mahkota Johor (Tunku Ismail Sultan Ibrahim) for being dragged into this slander involving my brother Prebet Adam.

“I want to clarify that there were no deaths involving our siblings due to murder. All of us are still alive except for one who passed away in 1975 in a fire.

“In the name of Allah, there was no murder at all,” she told a press conference at her house in George Town on Thursday, a video of which Malay daily Berita Harian uploaded to its YouTube channel.

The video also shows two other siblings present during the press conference, Arina and Arman. Adam is the eldest of nine siblings.

The urban legend over the Chow Kit incident was that the brother was supposedly a golf caddy who had laughed at Sultan Iskandar when the ruler missed a shot.

The late Sultan had then supposedly hit Adam’s brother on the head with a golf club, causing his death.

On Oct 17, 1987, Adam, then a 23-year-old soldier, stole an M16 rifle and a motorcycle from his army camp in Ipoh.

The army Ranger Regiment sharpshooter then rode to Kuala Lumpur.

The next night, he wrote a message on his hotel room mirror: “A damned night for Adam. Mission: to kill or be killed.”

He left his hotel and went on a shooting spree in the city’s Chow Kit area that left one person dead from a bullet ricochet and several others wounded.

Adam shot at cars and at a petrol station fuel tank that burst into flames. He eventually surrendered and at his trial, his defence lawyer entered a plea of temporary insanity.

At the press conference on Thursday, Hawa said the family does not know any member of the Johor royal family and pleaded with the media to help tell the real story and to inform the Tunku Mahkota Johor of their apology.

“We have been accused of receiving RM10,000 monthly to deny the murder. Just look at my house.

“We are merely commoners and have never received a single cent from anyone to deny this matter.

“I just want to ask for justice for those who have been victims of slander due to this,” said Hawa.

The Prebet Adam controversy resurfaced when Tunku Ismail, the Johor crown prince, shared his views on the country’s political situation in a post on the Johor Southern Tigers Facebook page on Sunday (April 8).

He touched on the story of Prebet Adam, saying that his late grandfather Almarhum Sultan Iskandar was not given a chance to defend himself as royalty did not have the luxury of the Internet, and the mainstream media were controlled by the government of the day.

The Prebet Adam urban legend was also debunked in a book published last May, titled Konfesi Prebet Adam.

Its author Syahril A. Kadir posted on Facebook that he forgave those who made allegations and criticised him for writing the book.

“Some said that I created stories to clear the name of the Almarhum Sultan Johor.

“I was accused of receiving dedak (bribes) and insulted but I accepted it because I know I’m on the right side. Finally, Prebet Adam’s own family has clarified what actually happened,” he wrote.

Syahril’s book was based on interviews with key figures in the case, and includes first person accounts by Adam himself, his lawyer Tan Sri Muhammad Shafee Abdullah, and Leftenan Jeneral (R) Datuk Abdul Ghani Abdullah, the military officer who managed to persuade Adam to surrender.

BTW the portion of your post regarding the late Sultan of Johor is almost certainly seditious.

ReplyDeleteHamish Mcdonald, a British writer with probably no intention of ever stepping foot in Malaysia again, could safely wrote that article, but not Ktemoc to publish it....wajajaja..

Nothing seditious because....

ReplyDeleteBunuh, Rogol, Curi masuk Islam + Umrah = BEBAS, SUCI, BERSIH ...So already Went to Mecca ...ALL Clear....Next Case of terror and make Malaysial Stupid Please... Death to Malaysial of Arab Malay Islam descend!