KINIGUIDE | What they didn't tell you about the Middle East war

Steven Gan

Published: Oct 8, 2025 8:00 AM

Updated: 5:07 PM

KINIGUIDE | At the heart of the Israel–Palestine conflict is something simple - land, rights, and justice.

The Israel-Palestine conflict did not begin on Oct 7, 2023, when Hamas attacked Israel.

What sparked the dispute?

Let’s be clear from the outset: the struggle for Palestine has always been about land and self‑determination, not primarily about religion. Its roots lie in two major betrayals of the Palestinian people by Western powers.

During World War I, the Ottoman Empire sided with Germany. When the Ottomans lost, their empire - which spanned much of the Middle East - was carved up by the victorious powers. Britain and France divided the region between them as the spoils of war.

Among other territories, Britain was handed a “mandate” over Palestine, supposedly to administer the territory until it could govern itself. But that was never the real plan.

Even before the war ended, Britain had already issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917. This pledged support for the creation of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine.

Crucially, the declaration was made without consulting the indigenous Arab population, who made up more than 90 percent of the inhabitants.

In plain terms, Britain was giving away land that did not belong to them - at the expense of the people who already lived there.

Soon after, Britain actively facilitated mass Jewish immigration from Europe into Palestine. The Jewish population, which had been about five percent before, swelled to around 30 percent within just three decades.

Why did Jews seek to emigrate to Palestine?

Centuries of persecution in Europe - culminating in the Holocaust during World War II - forced many Jews to seek refuge elsewhere. The Zionist movement, which emerged in the late 19th century, encouraged this migration.

It presented itself as a national liberation movement for the Jewish people, calling for a return to their ancestral land and the exercise of self‑determination there.

Zionists based their claim on millennia of continuous historical and religious connection to Palestine, which they argued gave them a unique right to establish a state in that land.

They claimed that because of their history of persecution, they had a “special right” to a national home in Palestine.

But this crisis was born in Europe, not the Middle East. The “solution” was imposed on a non‑European land already inhabited by other people. In addition, European and Western nations restrict Jewish immigration, leaving Holocaust survivors with few options.

When European and Western nations failed to take in Jewish refugees, desperate Holocaust survivors were pushed toward Palestine. In effect, Europe outsourced its “Jewish problem” to the Middle East.

The Jewish tragedy - centuries of persecution and the Holocaust - was a European problem that required a European solution. Instead, the solution chosen was the creation of Israel on Arab land, at the expense of an innocent third party: the Palestinians, who had no role in the persecution of Jews.

Seen in this light, the Zionist project was not a simple “return of a native people,” but a form of European colonialism. And Palestinians were forced to pay the price - the loss of their homeland - for crimes committed in Europe, by Europeans.

What was the second major betrayal of Palestinians by Western powers?

The second betrayal came in 1947-48, when the United Nations proposed partitioning Palestine into separate Arab and Jewish states. Again, this plan was drawn up without the democratic consent of the Palestinian population. They were effectively denied a say in their own future.

Moreover, the partition plan was heavily skewed in favour of the Zionists. Although Jews made up only about one‑third of the population, they were allocated nearly two‑thirds of the land.

This included major cities and much of the fertile coastal plain. Even more striking, the Jewish community, which owned only about seven percent of private land, was suddenly granted 56 percent of the territory.

Palestinians argued that the UN had no legal or moral right to hand over the majority of their country to a minority of recent immigrants against their will. Instead, they called for a single, democratic state for all its inhabitants, regardless of religion or ethnicity.

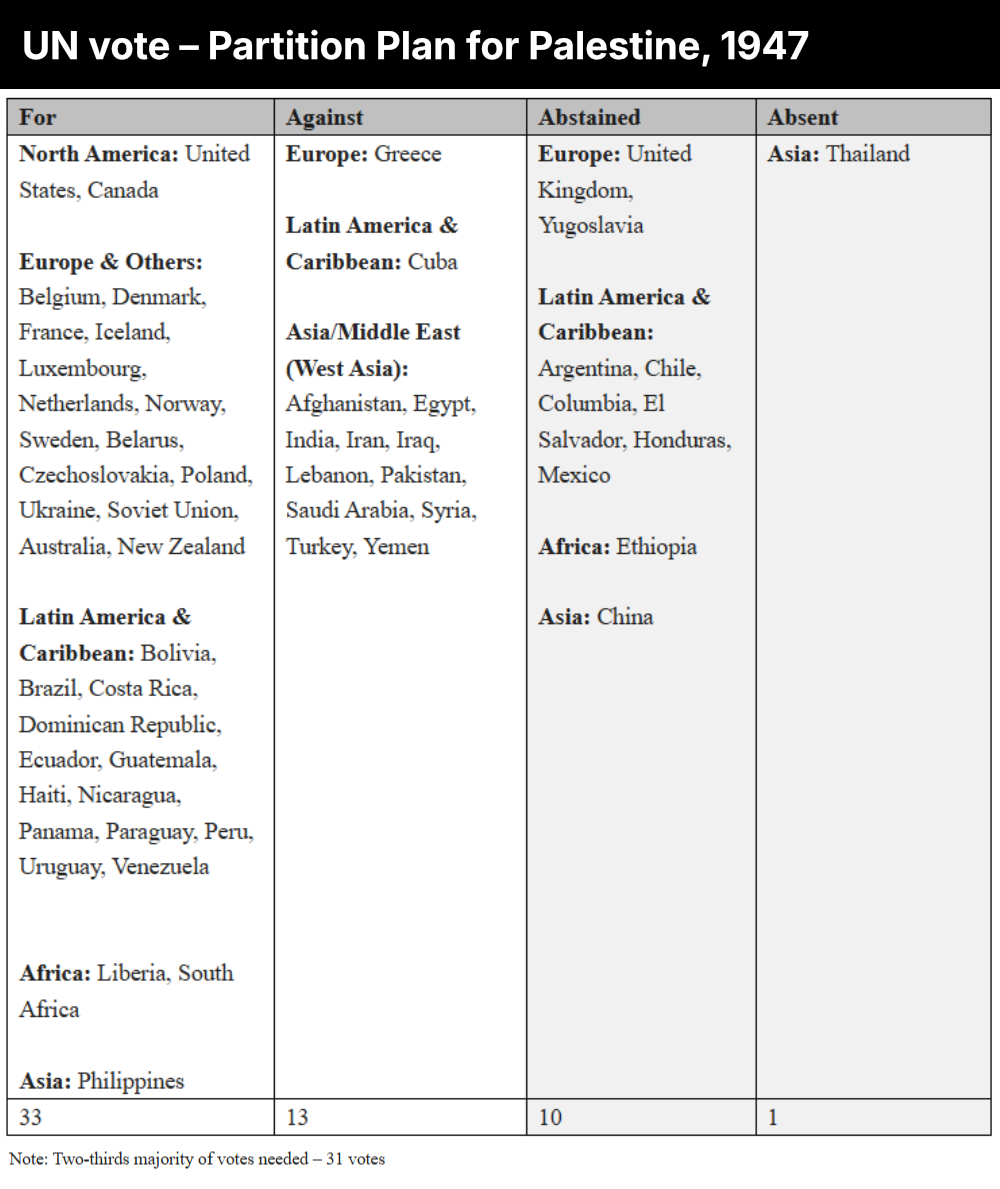

At the time, the UN itself was dominated by colonial powers. Much of Africa and Asia was still under colonial rule and had no say in the matter. Of the 57 member states then in the UN, 33 voted for partition, 13 voted against, and 10 abstained. A two‑thirds majority - 31 votes - was required, so the plan passed.

Those in favour were mostly European states and colonial‑settler countries in the Americas, along with Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Those opposed included the Arab nations, as well as newly independent India and Pakistan.

In Asia, only the Philippines voted in favour - after a last‑minute change under pressure from its former colonial master, the US. China, then under the Kuomintang, abstained.

Thailand was the sole absentee: its credentials were questioned after it had voted against partition in committee, and it was barred from the final vote.

In approving the partition, the UN acted in a way that mirrored colonial practices: deciding the fate of a territory and its people without their consent. It violated its own stated commitment to decolonisation and self‑determination.

In effect, the UN sought to solve a European problem - the fate of Holocaust survivors and Zionism’s demand for a state - at the expense of a Middle Eastern population, the Palestinian Arabs.

If Jews, like all peoples, have a right to self‑determination, why shouldn’t Israel’s creation be seen as the fulfilment of that right?

Self‑determination is indeed a fundamental right - the right of every people to shape their own affairs and build their own society. From the Israeli perspective, the creation of their state was both a necessary response to centuries of persecution and the fulfilment of an ancient connection to Palestine.

However, Palestinians - both Muslim and Christian - assert their continuous presence in the land for millennia. They trace their roots through diverse populations across the ancient, Byzantine, Arab‑Islamic, and Ottoman periods, and see themselves as the indigenous people of Palestine.

Historical records confirm that while the region has seen many rulers and demographic shifts, Arab Muslims and Christians made up the overwhelming majority of the population for centuries, leading up to the 20th century.

The Zionist counter‑claim is that continuous majority residency is not the decisive principle when the issue concerns the national birthplace of a displaced people. Yet this narrative selectively highlights Jewish historical ties while downplaying or erasing the continuous presence and rights of other communities.

Even if one accepts the Zionist argument about historic Jewish links to Palestine, the record is clear: over the past 3,000 years, Jews ruled the area for a cumulative total of about 600 years.

By contrast, Arab and Muslim powers controlled it for roughly 1,300 years. Even Roman and Byzantine rule lasted longer than Jewish rule - about 700 years.

Against this backdrop, the establishment of a Jewish state in a land predominantly inhabited by Palestinians amounted to a denial of the Palestinians’ pre‑existing right to self‑determination.

One people’s right to self‑determination cannot legitimately be exercised at the expense of another people’s right to self‑determination - especially when that other people is indigenous to the land. Granting a minority a state at the expense of the majority was, and remains, a profound injustice.

This is not a question of whether Jews deserve self‑determination. It is a question of how that self‑determination was achieved, and at what cost to the Palestinian people who were already living there.

Zionists often spoke of “a land without a people for a people without a land.” But Palestine was not “without people”.

Indeed, Palestine was never empty. For centuries, it was home to a predominantly Arab population, both Muslim and Christian.

Alongside them lived a small but continuous Jewish community, making up about five percent of the population before the large waves of immigration from Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Zionist slogan of “a land without people” was not just inaccurate - it was politically loaded. It denied the existence and national aspirations of Palestinians. By implying they were not “a people” in any meaningful sense, it suggested their claims to the land were negligible or irrelevant.

This is a classic colonial tactic: to justify settlement by portraying the indigenous population as sub-human, uncivilised, or unworthy of sovereignty.

Displaced Gazans

In this way, the Zionist narrative erased Palestinians from their own homeland, paving the way for dispossession to be framed as destiny rather than injustice.

What happened after the vote?

The Palestinians and the surrounding Arab countries rejected the UN partition plan, and war soon followed. During and after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, between 700,000 and 750,000 Palestinians were forced from their homes.

Entire villages were destroyed, and their lands and property were seized by the newly established Israeli state. For Palestinians, this mass displacement is remembered as the Nakba - the catastrophe.

The injustice of the Nakba is compounded by Israel’s Law of Return. This law grants any Jew, from anywhere in the world, the automatic right to immigrate to Israel and obtain citizenship.

By contrast, Palestinians who were born in the land, lived there for generations, and were later forced to flee are denied the same right to return. This stark double standard is widely seen as a form of institutionalised discrimination - privileging one people’s claim to the land while erasing the rights of another.

The Hamas attack on Oct 7, 2023, was horrific. About 1,200 civilians were killed, and hundreds were taken hostage. The question many ask is: Doesn’t Israel have the right to fight these terrorists?

Israel often frames the story as if Palestinians alone have a monopoly on terrorism. But history tells a different story.

Take Irgun, a Zionist underground group that even the British authorities at the time described as a terrorist group. In the late 1940s, Irgun’s strategy was to terrorise Palestinians so they would flee their villages.

One of the most infamous examples was the Deir Yassin massacre, where over 100 men, women, and children were killed. News of the massacre spread fear across Palestine, contributing to the mass flight of Palestinians.

By the end of 1948, about half the Palestinian population had abandoned their homes and sought refuge in neighbouring Arab countries - Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria.

What happened after the vote?

The Palestinians and the surrounding Arab countries rejected the UN partition plan, and war soon followed. During and after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, between 700,000 and 750,000 Palestinians were forced from their homes.

Entire villages were destroyed, and their lands and property were seized by the newly established Israeli state. For Palestinians, this mass displacement is remembered as the Nakba - the catastrophe.

The injustice of the Nakba is compounded by Israel’s Law of Return. This law grants any Jew, from anywhere in the world, the automatic right to immigrate to Israel and obtain citizenship.

By contrast, Palestinians who were born in the land, lived there for generations, and were later forced to flee are denied the same right to return. This stark double standard is widely seen as a form of institutionalised discrimination - privileging one people’s claim to the land while erasing the rights of another.

The Hamas attack on Oct 7, 2023, was horrific. About 1,200 civilians were killed, and hundreds were taken hostage. The question many ask is: Doesn’t Israel have the right to fight these terrorists?

Israel often frames the story as if Palestinians alone have a monopoly on terrorism. But history tells a different story.

Take Irgun, a Zionist underground group that even the British authorities at the time described as a terrorist group. In the late 1940s, Irgun’s strategy was to terrorise Palestinians so they would flee their villages.

One of the most infamous examples was the Deir Yassin massacre, where over 100 men, women, and children were killed. News of the massacre spread fear across Palestine, contributing to the mass flight of Palestinians.

By the end of 1948, about half the Palestinian population had abandoned their homes and sought refuge in neighbouring Arab countries - Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria.

Palestinians suffer as a result of Israel blocking aid to Gaza

Irgun’s leader, Menachem Begin, was directly involved in the 1946 bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, which killed 91 people. The British even banned him from entering the UK. Yet this same man later became Israel’s prime minister - and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

None of these excuses Hamas’ crimes on Oct 7. But it does raise a troubling question: how different are those acts from the state‑enabled violence carried out by Israel and its settlers in the West Bank?

Palestinians there face arson attacks, destruction of property, physical assaults, and intimidation - often with little or no accountability. When such acts are committed to drive Palestinians from their land or to expand settlements, they amount to state‑backed terrorism.

St Augustine once told a story in City of God about Alexander the Great and a pirate.

Alexander asked, “How dare you molest the seas?” The pirate replied, “How dare you molest the whole world? Because I do it with a small boat, I’m called a pirate. You, with a great navy, molest the world and are called an emperor.”

The parallel is hard to miss.

Doesn’t Israel have the same right to self‑defence as any other state?

Under international law, an occupying power cannot claim self‑defence against resistance that arises from within the territory it occupies.

Israel’s occupation of Palestinian lands since 1967 is widely regarded as illegal. If the occupation itself is unlawful, then actions taken to sustain it cannot be framed as legitimate self‑defence.

The appeal to “self‑defence” is, in fact, a powerful rhetorical device. It casts Israeli actions as reactive and morally justified, while erasing the broader context of occupation, blockade, and displacement.

This framing flips the script: Israel is portrayed as the victim responding to unprovoked aggression, rather than as an occupying power whose own policies fuel the cycle of violence.

Of course, force is often met with force. But Israel cannot use “self‑defence” as a blanket justification for its conduct. The claim has even been stretched to cover actions far beyond the occupied territories - such as attacks on Iran and the targeted killings of nuclear scientists and their families - all presented under the same banner of “self‑defence.”

Why did Israel suddenly attack Iran?

We have seen this pattern before. In 1981, Israel bombed Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor. Two decades later, the US‑led invasion of Iraq - justified on the claim of weapons of mass destruction - failed to uncover any such weapons, but left more than 200,000 people dead.

None of these excuses Hamas’ crimes on Oct 7. But it does raise a troubling question: how different are those acts from the state‑enabled violence carried out by Israel and its settlers in the West Bank?

Palestinians there face arson attacks, destruction of property, physical assaults, and intimidation - often with little or no accountability. When such acts are committed to drive Palestinians from their land or to expand settlements, they amount to state‑backed terrorism.

St Augustine once told a story in City of God about Alexander the Great and a pirate.

Alexander asked, “How dare you molest the seas?” The pirate replied, “How dare you molest the whole world? Because I do it with a small boat, I’m called a pirate. You, with a great navy, molest the world and are called an emperor.”

The parallel is hard to miss.

Doesn’t Israel have the same right to self‑defence as any other state?

Under international law, an occupying power cannot claim self‑defence against resistance that arises from within the territory it occupies.

Israel’s occupation of Palestinian lands since 1967 is widely regarded as illegal. If the occupation itself is unlawful, then actions taken to sustain it cannot be framed as legitimate self‑defence.

The appeal to “self‑defence” is, in fact, a powerful rhetorical device. It casts Israeli actions as reactive and morally justified, while erasing the broader context of occupation, blockade, and displacement.

This framing flips the script: Israel is portrayed as the victim responding to unprovoked aggression, rather than as an occupying power whose own policies fuel the cycle of violence.

Of course, force is often met with force. But Israel cannot use “self‑defence” as a blanket justification for its conduct. The claim has even been stretched to cover actions far beyond the occupied territories - such as attacks on Iran and the targeted killings of nuclear scientists and their families - all presented under the same banner of “self‑defence.”

Why did Israel suddenly attack Iran?

We have seen this pattern before. In 1981, Israel bombed Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor. Two decades later, the US‑led invasion of Iraq - justified on the claim of weapons of mass destruction - failed to uncover any such weapons, but left more than 200,000 people dead.

The issue of Israel’s attack on Iran deserves a full KiniGuide of its own, but here are some key points of context:

1. The 1953 coup in Iran. In 1953, Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, was overthrown in a coup orchestrated by Britain’s MI6 and the CIA.

Mosaddegh had sought to nationalise Iran’s oil industry, which was then controlled by a British company (later known as BP). Fearing the loss of its oil interests, Britain persuaded the US to help restore the autocratic rule of Shah Reza Pahlavi, who was seen as pro‑Western and compliant.

This coup laid the groundwork for decades of resentment and directly contributed to the conditions that led to the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which ultimately toppled the Shah.

2. Israel’s nuclear arsenal and double standards. Israel itself possesses nuclear weapons - estimated at around 90 warheads - and refuses to join the Nuclear Non‑Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Yet it insists that other states in the region, such as Iraq and Iran, must not develop nuclear capabilities.

For many, this is a glaring hypocrisy: a state that developed its own arsenal outside international safeguards now claims the right to prevent others from pursuing even civilian nuclear programmes.

3. Calls for a nuclear‑free Middle East. Iran, along with many other states in the region, has long advocated for the creation of a Middle East Nuclear‑Weapon‑Free Zone.

Such a framework would require all states - including Israel - to give up nuclear weapons and place their facilities under international inspection.

This proposal has been consistently blocked, largely because of Israel’s refusal to participate.

Many human rights groups have accused Israel of practising apartheid. Isn’t that a bit of a stretch?

Not really. In 2018, Israel passed the Nation‑State Law, which declares that the right to national self‑determination in Israel is “unique to the Jewish people”.

This clause formally elevates the collective rights of Jews above all other groups in the state. It denies Palestinians - including the Arab citizens of Israel, who make up about 20 percent of the population - any collective right to national self‑determination in their own country.

By making that right exclusive to Jews, the law effectively relegates non‑Jewish citizens to second‑class status.

The inequality is even starker in the occupied territories. Palestinians there live under Israeli military law and are tried in military courts, while Jewish settlers in the very same areas are governed by Israeli civil law. This dual legal system entrenches systematic discrimination.

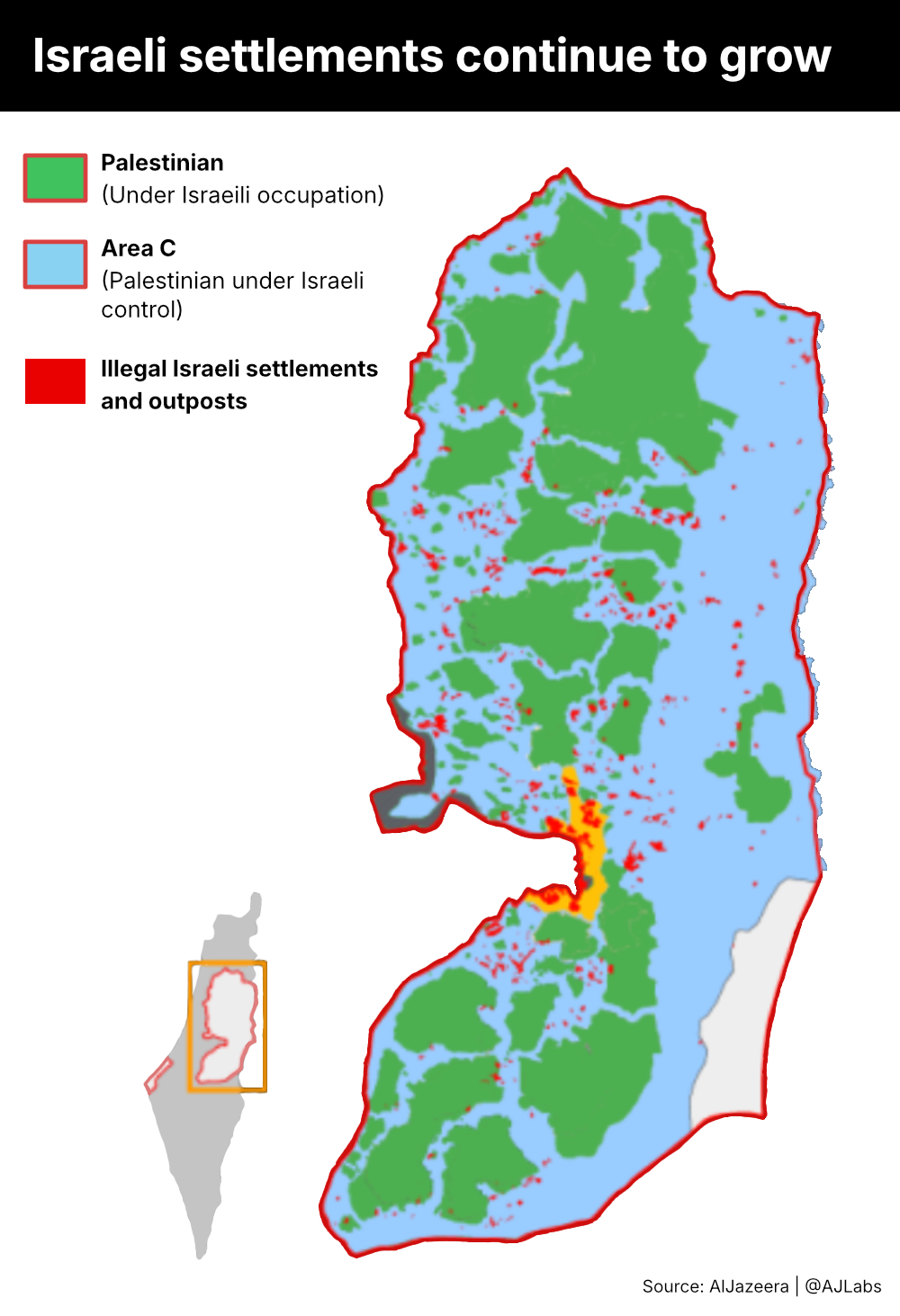

On top of this, Palestinians face severe restrictions on movement: checkpoints, permits, and a segregated road network that Jewish settlers are free to use. At the same time, Palestinian land is systematically expropriated for the construction and expansion of Jewish settlements - settlements that are illegal under international law.

Taken together, these policies advance and entrench the supremacy of one group - Jews - over another - Palestinians. This is precisely what human rights organisations mean when they describe Israel’s system as apartheid.

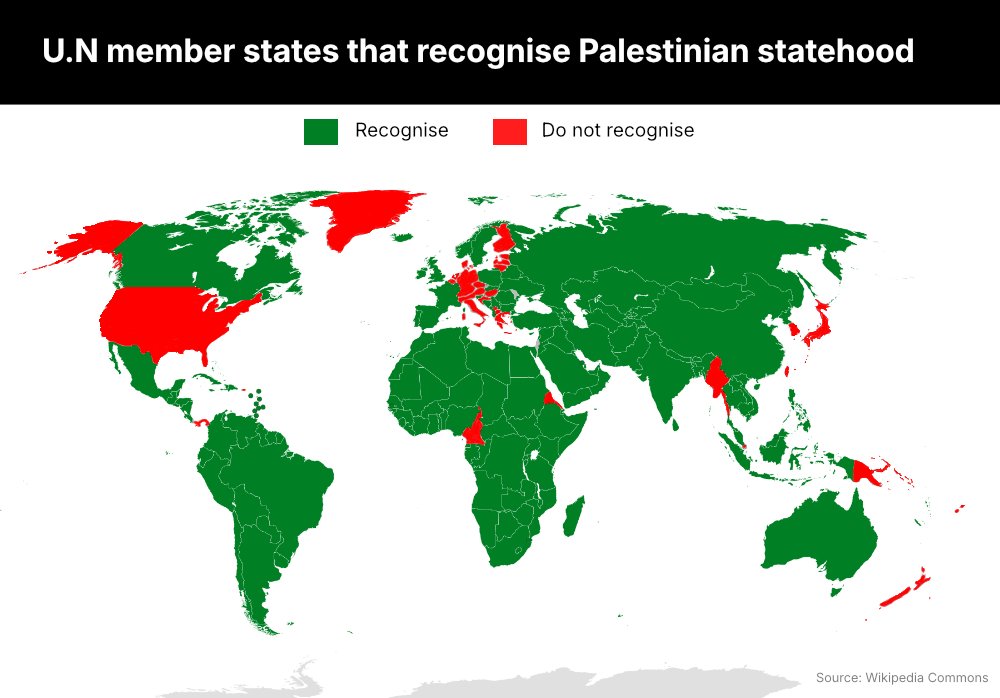

There appear to be more countries recognising the state of Palestine.

Today, more than 80 percent of the world’s countries - 157 out of 193 UN member states - recognise the state of Palestine. Some of the most recent additions to this growing list include Britain, France, Canada, and Australia.

The main holdouts are the United States, several European countries led by Germany, and a handful of Pacific nations. In Asia, recognition is nearly universal, with only a few major exceptions such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore.

Israel has long demanded that others recognise its right to exist. Yet it refuses to extend the same recognition to Palestine. Those states that still withhold recognition of Palestine often argue that it should come only as part of a negotiated peace deal.

But this logic is one‑sided: Israel’s right to exist is treated as non‑negotiable and absolute, while Palestine’s right to exist is treated as conditional.

The recent wave of recognition from major Western nations is significant, but for many Palestinians, it comes too late. A glance at the map of the West Bank shows why: more than 700,000 Israeli settlers now live there, and their numbers continue to grow. How can such a vast settler population realistically be removed?

Faced with this reality, some now argue that the only just solution may be a single, democratic, secular state across all of historic Palestine - one in which every citizen, regardless of religion or ethnicity, enjoys equal rights. This, in fact, was the vision Palestinians advocated for a century ago.

Israel refuses to recognise Palestine, so what does it really want?

What Israel seeks is “permanent security control without Palestinian statehood” in the occupied territories.

In practice, this means retaining the security benefits of full control while offloading the civilian administrative burden onto local or international bodies - all the while systematically denying Palestinians their core demand for self‑determination.

Even if one accepts that Israel’s security concerns are genuine, they are often invoked as a pretext to maintain territorial control and to block the creation of a viable Palestinian state, rather than as part of a sincere effort to achieve a lasting two‑state peace.

The underlying aim is to keep Palestinians subdued and dependent, in the hope that over time they will simply fade into political irrelevance.

The long history of peace agreements illustrates this imbalance. Most were brokered by the US - hardly a neutral mediator given its consistent support for Israel - and were skewed in Israel’s favour.

The most recent plan, advanced by US President Donald Trump, was no different. It sidelined an Egyptian‑led proposal: a technocratic Palestinian interim government, the restoration of a democratically elected Palestinian leadership, and a reconstruction of Gaza designed, led, and implemented by Palestinians themselves.

For some, particularly religious Zionists, the issue goes even deeper. They believe the land is divinely promised, and that relinquishing any part of it - especially the West Bank, which they call Judea and Samaria - would be a betrayal of religious principles.

For them, there can only be Israel, and no Palestine. In this vision, the logical outcome is not coexistence but ethnic cleansing - the expulsion of the Palestinian population.

But the pro-Israeli camp, too, has very compelling arguments

Yes. After all, Israel is backed by some of the richest and most powerful forces in the world, and its narratives have often been amplified by global media.

When even the New York Times - widely regarded as the gold standard of journalism - cannot bring itself to use the word “genocide” to describe what is happening in Gaza, it signals how constrained the discourse has become.

This is why groups like Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis are routinely labelled “proxies” by Western media while Israel is consistently described as a “strategic ally” - despite the fact that the US has provided Israel with a cumulative US$174 billion (RM733.3 billion) in aid, more than to any other country in the world.

Consider, too, how the media blindly reported that “40 babies were decapitated” by Hamas militants - a claim that was never substantiated and ultimately proven false.

In an age of rising anti‑Semitism and Islamophobia, false narratives will inevitably circulate on both sides of the divide, especially on social media. But when mainstream outlets give credence to such explosive misinformation, it reveals a deeper bias in the way stories are framed and consumed.

In our post‑truth era, where emotion and belief often outweigh evidence, fact‑checking is not optional. It is essential.

Even if one concedes some of the Zionist claims, the moral balance remains heavily weighted toward the Palestinians - a people whose fundamental human rights and right to self‑determination were violated during the establishment and expansion of Israel.

From this perspective, the Palestinian claim, rooted in the ongoing consequences of dispossession and occupation, carries far greater moral and legal weight.

At its core, the conflict is about a group of outsiders - predominantly European settlers - taking land that belonged to Palestinians, with the backing of powerful Western governments.

Any just solution must begin by acknowledging this history and the injustice it created. The question is no longer whether Palestinians deserve freedom. The real question is how long the world will continue to allow that freedom to be denied.

This KiniGuide was compiled by Steven Gan, co-founder of Malaysiakini. For a basic primer on the issue, see this piece published by Al Jazeera in the wake of the Oct 7, 2023, attack.

***

In the face of such gross injustice the Heavens must speak up and act

No comments:

Post a Comment