BOOK REVIEW | Glimpses of the judiciary - good and bad

R Nadeswaran

BOOK REVIEW | The judicial crisis of the mid-1980s started with the sacking of the then chief justice, Salleh Abas. This was followed by an exposé in 2000 by Malaysiakini editor-in-chief Steven Gan on another chief justice, Eusoff Chin and his family, who had been holidaying with lawyer VK Lingam.

This had sent shockwaves in the fraternity and even a royal commission of inquiry failed to restore the then much-needed confidence in the judiciary. Moreover, there were other claimed incidents of “interference” - which did not come into the public domain.

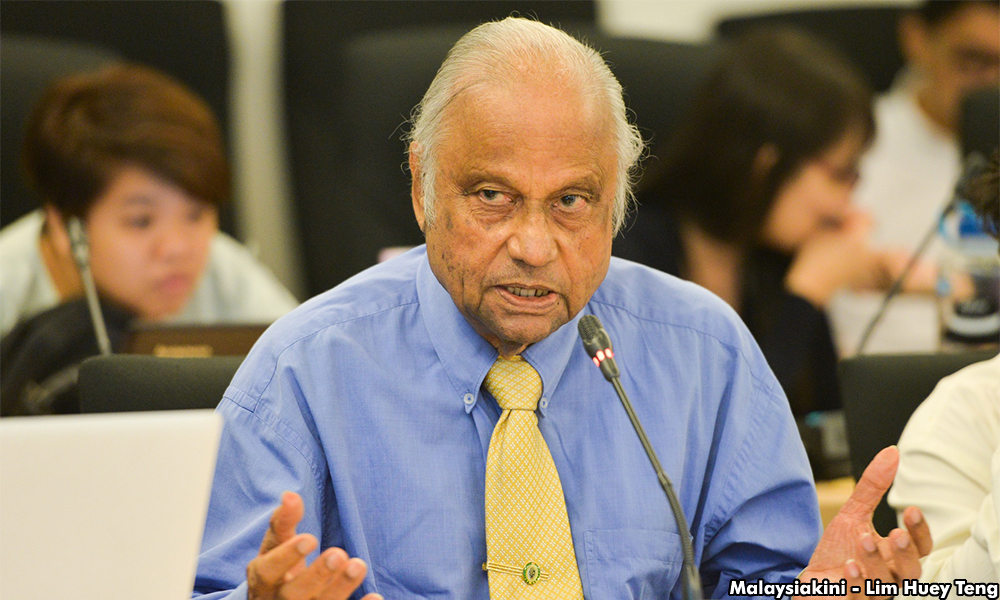

Mahadev Shankar, who was then a High Court judge based in Johor Bahru, was drawn unwittingly - not as a player but as a witness - to this shameful episode in the history of the judiciary by a strange turn of events.

BOOK REVIEW | The judicial crisis of the mid-1980s started with the sacking of the then chief justice, Salleh Abas. This was followed by an exposé in 2000 by Malaysiakini editor-in-chief Steven Gan on another chief justice, Eusoff Chin and his family, who had been holidaying with lawyer VK Lingam.

This had sent shockwaves in the fraternity and even a royal commission of inquiry failed to restore the then much-needed confidence in the judiciary. Moreover, there were other claimed incidents of “interference” - which did not come into the public domain.

Mahadev Shankar, who was then a High Court judge based in Johor Bahru, was drawn unwittingly - not as a player but as a witness - to this shameful episode in the history of the judiciary by a strange turn of events.

Former judge Mahadev Shankar

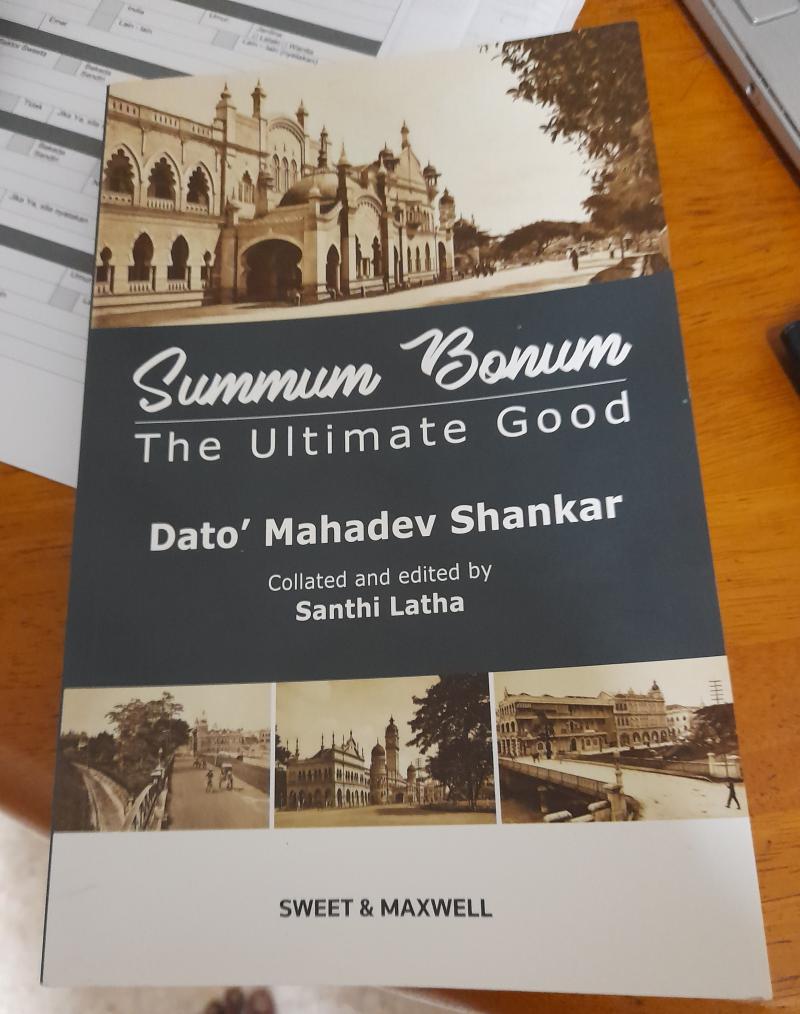

In his book, ‘Summum Bonum (The Ultimate Good)’, Shankar provides intricate details of how he and another Kuala High Court judge were summoned to the then chief justice Abdul Hamid Omar’s office in Kuala Lumpur.

“When the chief justice arrived, he told me, peremptorily, that I was to leave Johor the following week and take over Zakaria Yatim’s court the following Monday. No reason was given, and at such short notice was absolutely unusual. Something was amiss, but I had no idea then what it was,” he writes.

When the Court of Appeal was set up in 1994 as an intermediate court between the High Court and the Federal Court, both Shankar and Zakaria were in the pioneer batch of judges who were elevated.

Denial of bail

After the elevation, both the judges met and it was then that he discovered what caused Zakaria’s unusual and immediate transfer and why he was ordered to swap places with Shankar. Simply put, Zakaria refused to “play ball” with the powers-that-be.

Zakaria revealed that there had been a financial scandal in Hong Kong involving the owners of Kah Wah Bank. The managing director fled to Taiwan but his younger brother had come to Kuala Lumpur and had been arrested by the police and was facing extradition proceedings.

He had applied for bail and Zakaria was assigned to hear the case. Shankar writes: “He had received a coded message to give favourable consideration to the applicant – the message was very nuanced but the meaning was clear.”

He then quotes Zakaria verbatim: “In that dilemma, I chose to reject the bail application and facilitate the extradition. What happened after that was my immediate fall from grace. It did not occur to me then to take the path of least resistance, because I only realised subsequently that had I granted bail, nothing would have happened to me because I had judicial immunity and all they could do was to appeal from my order.” (emphasis is Shankar’s)

The book traces Shankar’s days in school, his sojourn in London to read law, practising as a lawyer thereafter, his subsequent elevation to the Bench and his retirement.

His astute observations are not restricted to just such episodes and he gives views on a range of subjects and personalities.

He writes extensively on the hijacking of the Malaysia Airlines (MAS) plane which crashed in Tanjung Kupang in Johor in 1979. Having been a member of the board, he was tasked with handling the legal issues related to the crash.

He admits that having spent time on the MAS board, he saw the virtue of trying to settle cases rather than litigate. In the course of litigation, he writes, he had made mortal enemies and on occasion, the hostility between lawyers was terrible.

Sometimes, he notes, the animosity in court spilled over and the lawyers did not have cordial relationships with each other until “we matured, many years later.”

“The more hard-fought the case. The greater the undercurrent of hostility,” he records.

Random tales

But Shankar also provides some delightful and lighter insides of the other side of the law.

In one chapter, which he has called “Random Tales”, Shankar relates some interesting incidents, both in and out of the courtroom. He has plenty to say about lawyers – friends and opponents in court – their skills and their idiosyncrasies.

The book provides the experiences and echoes with the era in which Shankar served both at the Bar and on the Bench. He relates his encounters in court as a litigation lawyer and provides insights into some cases in which he sat in judgment.

In his book, ‘Summum Bonum (The Ultimate Good)’, Shankar provides intricate details of how he and another Kuala High Court judge were summoned to the then chief justice Abdul Hamid Omar’s office in Kuala Lumpur.

“When the chief justice arrived, he told me, peremptorily, that I was to leave Johor the following week and take over Zakaria Yatim’s court the following Monday. No reason was given, and at such short notice was absolutely unusual. Something was amiss, but I had no idea then what it was,” he writes.

When the Court of Appeal was set up in 1994 as an intermediate court between the High Court and the Federal Court, both Shankar and Zakaria were in the pioneer batch of judges who were elevated.

Denial of bail

After the elevation, both the judges met and it was then that he discovered what caused Zakaria’s unusual and immediate transfer and why he was ordered to swap places with Shankar. Simply put, Zakaria refused to “play ball” with the powers-that-be.

Zakaria revealed that there had been a financial scandal in Hong Kong involving the owners of Kah Wah Bank. The managing director fled to Taiwan but his younger brother had come to Kuala Lumpur and had been arrested by the police and was facing extradition proceedings.

He had applied for bail and Zakaria was assigned to hear the case. Shankar writes: “He had received a coded message to give favourable consideration to the applicant – the message was very nuanced but the meaning was clear.”

He then quotes Zakaria verbatim: “In that dilemma, I chose to reject the bail application and facilitate the extradition. What happened after that was my immediate fall from grace. It did not occur to me then to take the path of least resistance, because I only realised subsequently that had I granted bail, nothing would have happened to me because I had judicial immunity and all they could do was to appeal from my order.” (emphasis is Shankar’s)

The book traces Shankar’s days in school, his sojourn in London to read law, practising as a lawyer thereafter, his subsequent elevation to the Bench and his retirement.

His astute observations are not restricted to just such episodes and he gives views on a range of subjects and personalities.

He writes extensively on the hijacking of the Malaysia Airlines (MAS) plane which crashed in Tanjung Kupang in Johor in 1979. Having been a member of the board, he was tasked with handling the legal issues related to the crash.

He admits that having spent time on the MAS board, he saw the virtue of trying to settle cases rather than litigate. In the course of litigation, he writes, he had made mortal enemies and on occasion, the hostility between lawyers was terrible.

Sometimes, he notes, the animosity in court spilled over and the lawyers did not have cordial relationships with each other until “we matured, many years later.”

“The more hard-fought the case. The greater the undercurrent of hostility,” he records.

Random tales

But Shankar also provides some delightful and lighter insides of the other side of the law.

In one chapter, which he has called “Random Tales”, Shankar relates some interesting incidents, both in and out of the courtroom. He has plenty to say about lawyers – friends and opponents in court – their skills and their idiosyncrasies.

The book provides the experiences and echoes with the era in which Shankar served both at the Bar and on the Bench. He relates his encounters in court as a litigation lawyer and provides insights into some cases in which he sat in judgment.

Santhi Latha (file picture)

Lawyer Santhi Latha, who collated and edited the book, spent thousands of hours from 2013 listening and putting Shankar’s thoughts and views on paper.

In her commentary, she says: “I have constantly been astounded by his memory but more, by how the hand of history has peppered his life with many people and circumstances I could have only learnt from history books.”

The book also provides perceptions of the law, its interpretations and above all, the key protagonists who made a name for themselves including some who made headlines for the wrong reasons.

The book will be launched by former Federal Court judge Zainun Ali on Saturday and is available at Kinokuniya KLCC, Cyrus Book Store and Crescent News.

R NADESWARAN is a veteran journalist. Comments: citizen.nades22@gmail.com

Lawyer Santhi Latha, who collated and edited the book, spent thousands of hours from 2013 listening and putting Shankar’s thoughts and views on paper.

In her commentary, she says: “I have constantly been astounded by his memory but more, by how the hand of history has peppered his life with many people and circumstances I could have only learnt from history books.”

The book also provides perceptions of the law, its interpretations and above all, the key protagonists who made a name for themselves including some who made headlines for the wrong reasons.

The book will be launched by former Federal Court judge Zainun Ali on Saturday and is available at Kinokuniya KLCC, Cyrus Book Store and Crescent News.

R NADESWARAN is a veteran journalist. Comments: citizen.nades22@gmail.com

Sounds like a book worth paying for.

ReplyDelete