Bahasa Melayu or Bahasa Malaysia? As Putrajaya tightens reins on national language, linguistic experts argue why it should be the former

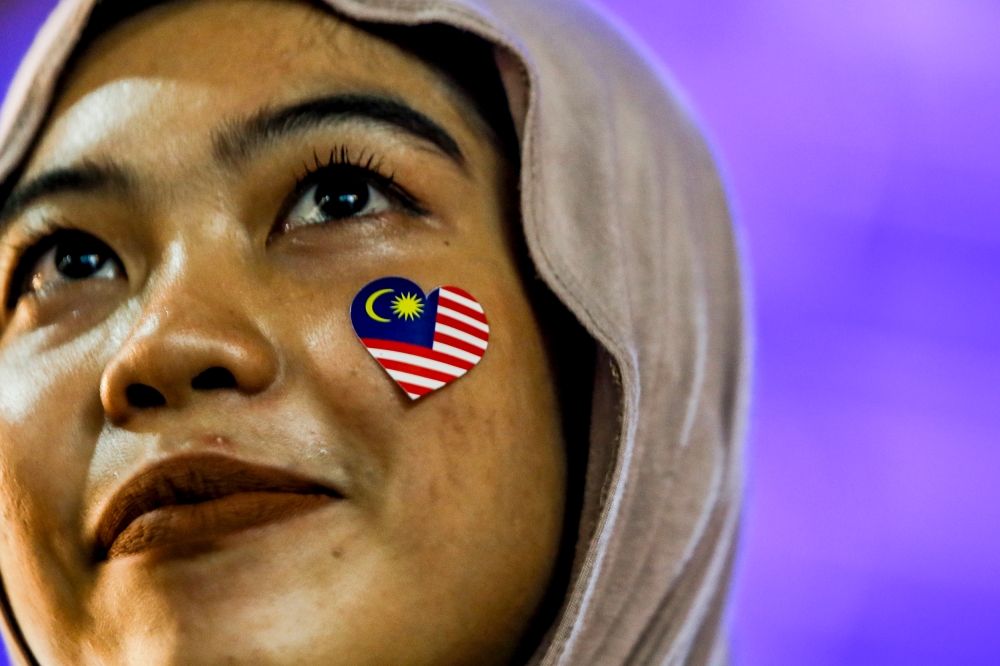

In Malaysia, all schools registered with the Ministry of Education are required to teach the Malay language as part of their curriculum, including vernacular, private and international schools. — Picture by Farhan Najib

Monday, 12 Feb 2024 7:00 AM MYT

KUALA LUMPUR, Feb 12 — Over the decades since the formation of Malaysia, its citizens have seen the name of its national language change several times between Bahasa Malaysia and Bahasa Melayu.

Amid discourse over the Anwar administration making its official use non-negotiable, several language experts polled by Malay Mail have said that it is time to call the language Bahasa Melayu once and for all — to cement its position and to ensure that the majority Malay community can preserve its heritage.

“The basis is that there is no such thing as Bahasa Malaysia, so Bahasa Melayu is the ‘rightful’ term,” said renowned Malay language academic Datuk Nik Safiah Karim.

“The problem is, in Malaysia, Malaysians have started to speak more English than Bahasa Melayu, this is one of the reasons why the language has become less popular and its identity weakened. Due to this, there is a huge lack of appreciation for the language today.”

The University of Malaya (UM) professor emeritus said that should the language be called Bahasa Melayu, it will help strengthen its position as it has now become “foreign” even among the Malays.

“Malays today speak Bahasa Melayu colloquially, but when it comes to the language proper, the standards have dropped. This is the reason why Malay students don’t do well in school examinations.

“But to improve this situation, the educators too need to be empowered. I know that on the ground, even some of the educators don’t have a strong grasp of Bahasa Melayu. So how then can they teach the language in schools effectively?” she asked.

Meanwhile, Malaysian Linguistic Society president Nor Hashimah Jalaluddin said linguistic academics across the world have always referred to it as Bahasa Melayu.

“My colleagues from all over the world will use Bahasa Melayu instead of Bahasa Malaysia because it has an astounding corpus and literature,” said the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia academic.

Mohamad Saleeh Rahamad, from UM’s Department of Media and Communication Studies, even went so far as warning that the Malay community will lose its heritage if they continue to be apologetic and accepting of citizens who do not use the language.

“If the Bahasa Melayu is lost, the Malay heritage is at risk of being forgotten as well. They will become foreign entities in the society of the future who have the current educational background.

“Each race should respectively defend the name [Bahasa Melayu] because this is proof of the nation’s existence, at the same time the nation’s values will erode rapidly if the language disappears,” Mohamad Saleeh said.

Under his new administration, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim had last year reminded all government departments not to entertain any letters written in a language other than the national language, while Home Minister Datuk Seri Saifuddin Nasution Ismail insisted that Malaysian passport holders should be proficient in the language.

Education Minister Fadhlina Sidek also announced that schools using Dual Language Programme (DLP) will be required to provide non-DLP classes in a bid to uphold the national language.

Monday, 12 Feb 2024 7:00 AM MYT

KUALA LUMPUR, Feb 12 — Over the decades since the formation of Malaysia, its citizens have seen the name of its national language change several times between Bahasa Malaysia and Bahasa Melayu.

Amid discourse over the Anwar administration making its official use non-negotiable, several language experts polled by Malay Mail have said that it is time to call the language Bahasa Melayu once and for all — to cement its position and to ensure that the majority Malay community can preserve its heritage.

“The basis is that there is no such thing as Bahasa Malaysia, so Bahasa Melayu is the ‘rightful’ term,” said renowned Malay language academic Datuk Nik Safiah Karim.

“The problem is, in Malaysia, Malaysians have started to speak more English than Bahasa Melayu, this is one of the reasons why the language has become less popular and its identity weakened. Due to this, there is a huge lack of appreciation for the language today.”

The University of Malaya (UM) professor emeritus said that should the language be called Bahasa Melayu, it will help strengthen its position as it has now become “foreign” even among the Malays.

“Malays today speak Bahasa Melayu colloquially, but when it comes to the language proper, the standards have dropped. This is the reason why Malay students don’t do well in school examinations.

“But to improve this situation, the educators too need to be empowered. I know that on the ground, even some of the educators don’t have a strong grasp of Bahasa Melayu. So how then can they teach the language in schools effectively?” she asked.

Meanwhile, Malaysian Linguistic Society president Nor Hashimah Jalaluddin said linguistic academics across the world have always referred to it as Bahasa Melayu.

“My colleagues from all over the world will use Bahasa Melayu instead of Bahasa Malaysia because it has an astounding corpus and literature,” said the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia academic.

Mohamad Saleeh Rahamad, from UM’s Department of Media and Communication Studies, even went so far as warning that the Malay community will lose its heritage if they continue to be apologetic and accepting of citizens who do not use the language.

“If the Bahasa Melayu is lost, the Malay heritage is at risk of being forgotten as well. They will become foreign entities in the society of the future who have the current educational background.

“Each race should respectively defend the name [Bahasa Melayu] because this is proof of the nation’s existence, at the same time the nation’s values will erode rapidly if the language disappears,” Mohamad Saleeh said.

Under his new administration, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim had last year reminded all government departments not to entertain any letters written in a language other than the national language, while Home Minister Datuk Seri Saifuddin Nasution Ismail insisted that Malaysian passport holders should be proficient in the language.

Education Minister Fadhlina Sidek also announced that schools using Dual Language Programme (DLP) will be required to provide non-DLP classes in a bid to uphold the national language.

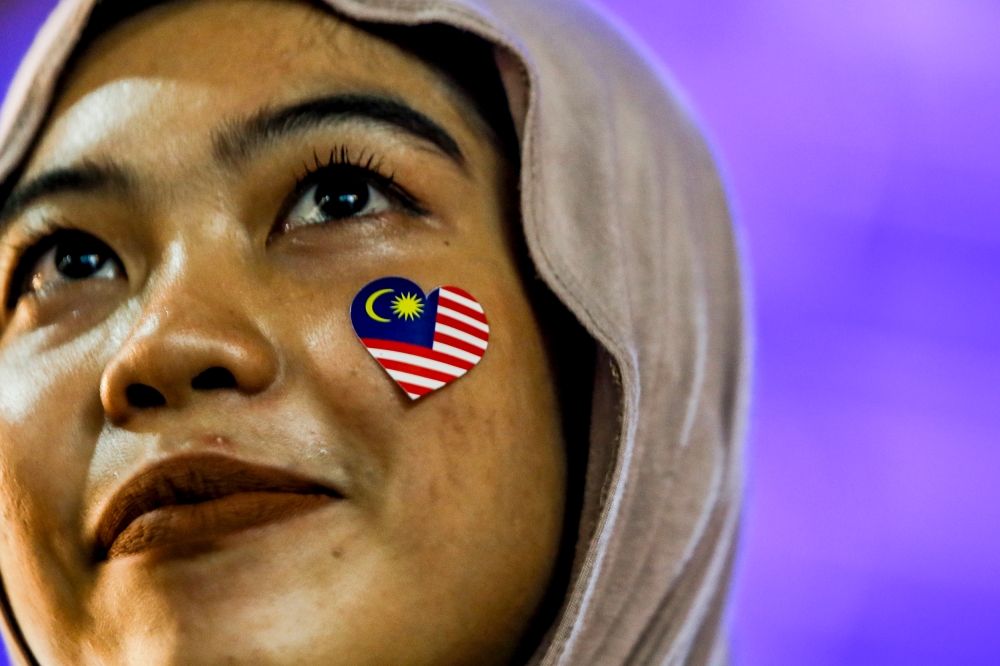

Mohamad Saleeh suggested that the flip-flop between Bahasa Melayu and Bahasa Malaysia was simply down to political reasons, as oftentimes the language was used as a political tool to suit the whims and fancy of politicians. — Picture by Hari Anggara

Why was it called Bahasa Malaysia?

In 2022, Malay linguistic expert Datuk Asmah Omar was reported justifying the use of the name “Bahasa Melayu” by citing the so-called Seven Wills of the Malay Rulers during Malaya’s independence, which among others declared that the national language is Bahasa Melayu.

Officially, Article 152(1) of the Federal Constitution calls the national language Bahasa Melayu. However, it was called Bahasa Malaysia after the formation of Malaysia in 1963 in a bid for national unity among the many ethnic groups that made up the country.

In 1986 under the Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad government, it was changed to be called Bahasa Melayu, but reverted to Bahasa Malaysia under Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi’s administration.

Hashimah called this “a wrong move”.

“We never call a language by the country but must name it according to the speakers. For example, we don’t have a British language but English, the Australians’ language is also English. It is not called ‘Indian language’ but Tamil, Hindi and so on.

“That’s why until today it never worked accordingly. From a linguistics point of view, the literature of a language is vital,” the professor said.

However, the secretary of the educationist group Parent Action Group for Education (Page), Tunku Munawirah Putra, said there was nothing wrong with using the two terms interchangeably as long as they are used in the right context.

“You must remember that before the Federal Constitution was drafted there was no Bahasa Melayu, so that’s why the term Bahasa Malaysia was used. It was only when the Federal Constitution was drafted that Bahasa Melayu was included in it.

“So as long as you use the terms accordingly, it should not cause any confusion or lead to any issues,” said Munawirah, who is the granddaughter of the country’s founding father Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra al-Haj.

She added that Bahasa Melayu should be known as ‘Bahasa Kebangsaan’ or the national language to ensure that the spirit of unity is kept intact.

Mohamad Saleeh suggested that the flip-flop between the two terms was simply down to political reasons, as oftentimes the language was used as a political tool to suit the whims and fancy of politicians.

“Hopefully now, the leaders of the country have the political will to uphold and protect the national language as it should have been done by previous leaders,” he said.

Why was it called Bahasa Malaysia?

In 2022, Malay linguistic expert Datuk Asmah Omar was reported justifying the use of the name “Bahasa Melayu” by citing the so-called Seven Wills of the Malay Rulers during Malaya’s independence, which among others declared that the national language is Bahasa Melayu.

Officially, Article 152(1) of the Federal Constitution calls the national language Bahasa Melayu. However, it was called Bahasa Malaysia after the formation of Malaysia in 1963 in a bid for national unity among the many ethnic groups that made up the country.

In 1986 under the Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad government, it was changed to be called Bahasa Melayu, but reverted to Bahasa Malaysia under Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi’s administration.

Hashimah called this “a wrong move”.

“We never call a language by the country but must name it according to the speakers. For example, we don’t have a British language but English, the Australians’ language is also English. It is not called ‘Indian language’ but Tamil, Hindi and so on.

“That’s why until today it never worked accordingly. From a linguistics point of view, the literature of a language is vital,” the professor said.

However, the secretary of the educationist group Parent Action Group for Education (Page), Tunku Munawirah Putra, said there was nothing wrong with using the two terms interchangeably as long as they are used in the right context.

“You must remember that before the Federal Constitution was drafted there was no Bahasa Melayu, so that’s why the term Bahasa Malaysia was used. It was only when the Federal Constitution was drafted that Bahasa Melayu was included in it.

“So as long as you use the terms accordingly, it should not cause any confusion or lead to any issues,” said Munawirah, who is the granddaughter of the country’s founding father Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra al-Haj.

She added that Bahasa Melayu should be known as ‘Bahasa Kebangsaan’ or the national language to ensure that the spirit of unity is kept intact.

Mohamad Saleeh suggested that the flip-flop between the two terms was simply down to political reasons, as oftentimes the language was used as a political tool to suit the whims and fancy of politicians.

“Hopefully now, the leaders of the country have the political will to uphold and protect the national language as it should have been done by previous leaders,” he said.

The secretary of the educationist group Parent Action Group for Education (Page) Tunku Munawirah Putra said that Bahasa Melayu should be known as ‘Bahasa Kebangsaan’ or the national language to ensure that the spirit of unity is kept intact. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

How will this issue impact non-Malays?

In justifying his call for the language to be called Bahasa Melayu, Mohamad Saleeh suggested that the forefathers’ aim to foster unity by calling it Bahasa Malaysia has failed.

“The term Bahasa Malaysia has all these times been used with hopes that everyone will be able to receive the language with utmost respect. However, that did not materialise.

“Bahasa Malaysia is still being ostracised, and it is not impossible that it will be sidelined even in the Malay heartland itself. This is where the country’s leaders play an important role to restore the term Bahasa Melayu,” he said.

Meanwhile, Nor Hashimah blamed the country’s attitude towards the language and its treatment of it.

“If we are a parallel school system with different languages, how can we expect the non-Malays to have an ample opportunity to appreciate Bahasa Melayu? Either Bahasa Melayu or Bahasa Malaysia, the perception remains the same. The exposure of non-Malays to Bahasa Melayu and the opportunities to use the language in respective schools is limited, not to mention outside the school premises.

“The pupils will stick to their friends and will never use Bahasa Melayu since they are comfortable with their own language. It’s not the name that matters to them, but the school with different languages that restrict them [from using the language],” she said.

In Malaysia, all schools registered with the Ministry of Education are required to teach the Malay language as part of their curriculum, including vernacular, private and international schools.

Educationist and Page founder Datin Noor Azimah Abdul Rahim also suggested that non-Malays would have little problem regardless of what the language is called.

“In terms of education, those who are teaching the language know that it is Bahasa Melayu, so there is no issues with that. I don’t think it would affect the non-Malays, as it was once known as Bahasa Melayu,” she said.

Malay language and literature activist Aminuddin Mansor — also known as Ami Masra — agreed with Noor Azimah.

“I don’t think this will change their perception of being a Malaysian, as they too have learned the language and know that it is the national language, as recorded in the Federal Constitution.

“So there is no huge ‘change’, as it was the country’s leaders who did not have a better understanding of Bahasa Malaysia, it does not exist. What exists is the country, Malaysia,” he told Malay Mail.

Nik Safiah also conceded that being in proficient Bahasa Melayu does not in any way mean that the non-Malays would have to forgo their mother tongue. She added that no Malaysian should limit the number of languages that they can speak.

“For me, you should speak as many languages as you can, but, because our national language is Bahasa Melayu, we should all [regardless of race] protect the national language and be proud to speak it fluently.

“I say this because it has come to a point whereby Malays are embarrassed to speak Bahasa Melayu as they associate it with being ‘less educated’ or of a lower social class. I have personally experienced this and it is a disappointing situation,” she said.

How will this issue impact non-Malays?

In justifying his call for the language to be called Bahasa Melayu, Mohamad Saleeh suggested that the forefathers’ aim to foster unity by calling it Bahasa Malaysia has failed.

“The term Bahasa Malaysia has all these times been used with hopes that everyone will be able to receive the language with utmost respect. However, that did not materialise.

“Bahasa Malaysia is still being ostracised, and it is not impossible that it will be sidelined even in the Malay heartland itself. This is where the country’s leaders play an important role to restore the term Bahasa Melayu,” he said.

Meanwhile, Nor Hashimah blamed the country’s attitude towards the language and its treatment of it.

“If we are a parallel school system with different languages, how can we expect the non-Malays to have an ample opportunity to appreciate Bahasa Melayu? Either Bahasa Melayu or Bahasa Malaysia, the perception remains the same. The exposure of non-Malays to Bahasa Melayu and the opportunities to use the language in respective schools is limited, not to mention outside the school premises.

“The pupils will stick to their friends and will never use Bahasa Melayu since they are comfortable with their own language. It’s not the name that matters to them, but the school with different languages that restrict them [from using the language],” she said.

In Malaysia, all schools registered with the Ministry of Education are required to teach the Malay language as part of their curriculum, including vernacular, private and international schools.

Educationist and Page founder Datin Noor Azimah Abdul Rahim also suggested that non-Malays would have little problem regardless of what the language is called.

“In terms of education, those who are teaching the language know that it is Bahasa Melayu, so there is no issues with that. I don’t think it would affect the non-Malays, as it was once known as Bahasa Melayu,” she said.

Malay language and literature activist Aminuddin Mansor — also known as Ami Masra — agreed with Noor Azimah.

“I don’t think this will change their perception of being a Malaysian, as they too have learned the language and know that it is the national language, as recorded in the Federal Constitution.

“So there is no huge ‘change’, as it was the country’s leaders who did not have a better understanding of Bahasa Malaysia, it does not exist. What exists is the country, Malaysia,” he told Malay Mail.

Nik Safiah also conceded that being in proficient Bahasa Melayu does not in any way mean that the non-Malays would have to forgo their mother tongue. She added that no Malaysian should limit the number of languages that they can speak.

“For me, you should speak as many languages as you can, but, because our national language is Bahasa Melayu, we should all [regardless of race] protect the national language and be proud to speak it fluently.

“I say this because it has come to a point whereby Malays are embarrassed to speak Bahasa Melayu as they associate it with being ‘less educated’ or of a lower social class. I have personally experienced this and it is a disappointing situation,” she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment