Ranjit Singh Malhi

HISTORY | Very little has been written about the substantial contributions of the Malaysian Tamil Muslims towards nation-building.

Originating from Tamil Nadu, India, and renowned as an entrepreneurial community with astute business acumen, the Tamil Muslims played a major role in promoting the nation’s early trade and commerce, pioneering Malay publications, establishing mosques, and bequeathing religious endowments.

Tamil Muslims who immigrated to what is currently Malaysia can be divided into three main groups: Marakkayar, a maritime trading community tracing their origins to Arab seafarers who married Indian women from the coastal regions of South India; Rowther, an originally landowning community famous for their cavalry and horse trade; and Lebbai, who were primarily engaged in religious scholarship.

Two other groups of Tamil Muslims came to Penang together with their families around the turn of the 20th century: Kadayanallur and Tenkasi Muslims, both being communities of handloom weavers, from the Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu.

Tracing back to the community’s earliest presence in the Malay Peninsula, there were Tamil Muslim traders in Kedah as early as the ninth century. These traders exchanged Indian textiles and rice for tin, pepper, and aromatic woods.

Subsequently, during the 15th century, Tamil Muslims rose to prominence in the Malacca Sultanate.

HISTORY | Very little has been written about the substantial contributions of the Malaysian Tamil Muslims towards nation-building.

Originating from Tamil Nadu, India, and renowned as an entrepreneurial community with astute business acumen, the Tamil Muslims played a major role in promoting the nation’s early trade and commerce, pioneering Malay publications, establishing mosques, and bequeathing religious endowments.

Tamil Muslims who immigrated to what is currently Malaysia can be divided into three main groups: Marakkayar, a maritime trading community tracing their origins to Arab seafarers who married Indian women from the coastal regions of South India; Rowther, an originally landowning community famous for their cavalry and horse trade; and Lebbai, who were primarily engaged in religious scholarship.

Two other groups of Tamil Muslims came to Penang together with their families around the turn of the 20th century: Kadayanallur and Tenkasi Muslims, both being communities of handloom weavers, from the Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu.

Tracing back to the community’s earliest presence in the Malay Peninsula, there were Tamil Muslim traders in Kedah as early as the ninth century. These traders exchanged Indian textiles and rice for tin, pepper, and aromatic woods.

Subsequently, during the 15th century, Tamil Muslims rose to prominence in the Malacca Sultanate.

Malacca sultanate display at Malacca museum.

As commented by Sinnappah Arasaratnam in his book, Indians in Malaysia and Singapore (1979), Tamil Muslims “occupied high positions in the court [Malacca Sultanate], inter-married with the royal family, and influenced political events.”

He adds further that they (together with other Indian Muslim merchants) “helped in its development and prosperity.”

For the record, the fourth and seventh bendaharas (prime ministers) of the Malacca Sultanate were Tamil Muslims: Sri Nara Diraja Tun Ali and Tun Mutahir (son of Tun Ali) respectively.

Other leading Tamil Muslims during the Malacca Sultanate were Tun Tahir and Tun Hassan, who both served as temenggung (chief of police).

Interestingly, Sultan Muhammad Syah of Malacca (1424‒44), the third ruler of the Malacca Sultanate, married a Tamil Muslim commoner, Tun Wati (Tun Ali’s sister) who bore him Sultan Muzaffar Syah (1446‒56). Similarly, Sultan Mansur Syah (1456–77), the sixth ruler of the Malacca Sultanate, married Tun Nur Pualam, Tun Ali’s daughter.

Moving on to the 17th century, most of the trade between India and the Malay Peninsula was dominated by the Tamil Muslims who were referred to, until the 19th century, as Chulias.

Chulias’ prominence

A little-known fact is that the Malay rulers of Kedah, Perak, Terengganu, and Johor appointed the Chulias as the king’s merchants or “saudagar raja” to manage their trading activities and to draft trade agreements with foreign traders.

This was due to the Chulias’ strong connection with a complex commercial and financing network, competence as sharp negotiators, and excellent accounting skills.

The Chulias’ shared religion with the Malays and their fluency in several languages were equally important factors for their prominence in the Malay courts and society.

Among the Chulias who became prominent “saudagar raja” were Sidi Lebbe and Tambi Kecil (given the title of Raja Mutabar Khan) in Perak; Syed Nina, Piro Mohamed, and Raja Jamal in Kedah; and Nasruddin Ali in Terengganu.

The Chulias also held important positions in the courts of Malay rulers. For example, Suraj Khan was reported to be the Syahbandar of Kedah in 1675. During the reign of Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin (1854–79), the government at Alor Setar was entrusted to a Chulia merchant, Bapu Kundor.

With the British occupation of Penang in 1786, most of the Chulias in Kedah relocated to Penang. Several of them subsequently became highly successful merchants, including Cauder Mohideen Merican (also known as Kader Mydin Merican), who was appointed as the first “Kapitan Kling” of Penang in 1801 by the British East India Company.

Cauder Mohideen’s brother, Mohamed Merican Noordin, became one of the most influential business figures in the 1830s through his transit barter trading in Indian textiles and pepper from Aceh.

Two other prominent Chulia merchants in 19th century Penang were Dalbadalsah Merican and Yahya Merican while Mohamed Ariff was a prosperous moneylender.

Based on the 1833 census, there were 7,886 Chulias in Penang and 510 in Province Wellesley. Subsequently, a large number of the Chulias (and other Indian Muslims) married local Malay women and assimilated into Malay society.

As commented by Sinnappah Arasaratnam in his book, Indians in Malaysia and Singapore (1979), Tamil Muslims “occupied high positions in the court [Malacca Sultanate], inter-married with the royal family, and influenced political events.”

He adds further that they (together with other Indian Muslim merchants) “helped in its development and prosperity.”

For the record, the fourth and seventh bendaharas (prime ministers) of the Malacca Sultanate were Tamil Muslims: Sri Nara Diraja Tun Ali and Tun Mutahir (son of Tun Ali) respectively.

Other leading Tamil Muslims during the Malacca Sultanate were Tun Tahir and Tun Hassan, who both served as temenggung (chief of police).

Interestingly, Sultan Muhammad Syah of Malacca (1424‒44), the third ruler of the Malacca Sultanate, married a Tamil Muslim commoner, Tun Wati (Tun Ali’s sister) who bore him Sultan Muzaffar Syah (1446‒56). Similarly, Sultan Mansur Syah (1456–77), the sixth ruler of the Malacca Sultanate, married Tun Nur Pualam, Tun Ali’s daughter.

Moving on to the 17th century, most of the trade between India and the Malay Peninsula was dominated by the Tamil Muslims who were referred to, until the 19th century, as Chulias.

Chulias’ prominence

A little-known fact is that the Malay rulers of Kedah, Perak, Terengganu, and Johor appointed the Chulias as the king’s merchants or “saudagar raja” to manage their trading activities and to draft trade agreements with foreign traders.

This was due to the Chulias’ strong connection with a complex commercial and financing network, competence as sharp negotiators, and excellent accounting skills.

The Chulias’ shared religion with the Malays and their fluency in several languages were equally important factors for their prominence in the Malay courts and society.

Among the Chulias who became prominent “saudagar raja” were Sidi Lebbe and Tambi Kecil (given the title of Raja Mutabar Khan) in Perak; Syed Nina, Piro Mohamed, and Raja Jamal in Kedah; and Nasruddin Ali in Terengganu.

The Chulias also held important positions in the courts of Malay rulers. For example, Suraj Khan was reported to be the Syahbandar of Kedah in 1675. During the reign of Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin (1854–79), the government at Alor Setar was entrusted to a Chulia merchant, Bapu Kundor.

With the British occupation of Penang in 1786, most of the Chulias in Kedah relocated to Penang. Several of them subsequently became highly successful merchants, including Cauder Mohideen Merican (also known as Kader Mydin Merican), who was appointed as the first “Kapitan Kling” of Penang in 1801 by the British East India Company.

Cauder Mohideen’s brother, Mohamed Merican Noordin, became one of the most influential business figures in the 1830s through his transit barter trading in Indian textiles and pepper from Aceh.

Two other prominent Chulia merchants in 19th century Penang were Dalbadalsah Merican and Yahya Merican while Mohamed Ariff was a prosperous moneylender.

Based on the 1833 census, there were 7,886 Chulias in Penang and 510 in Province Wellesley. Subsequently, a large number of the Chulias (and other Indian Muslims) married local Malay women and assimilated into Malay society.

A group of Tamil women in Province Wellesley (known as Seberang Perai today), Penang, 1907.

Their offspring were known as “Jawi Pekan” (“town Muslim”) or “Jawi Peranakan” (Indo-Malay community). The number of Jawi Peranakan in Penang increased from 3,491 in 1871 to 5,462 in 1881.

As stated by Helen Fujimoto in her book The South Indian Muslim Community and the Evolution of the Jawi Peranakan in Penang up to 1948 (1989), by the early years of the 20th century, the Jawi Peranakan increasingly identified themselves as Malays.

Indeed, the second and third generations of Jawi Peranakan received scholarships as Malays, entered into the civil service, and served with distinction.

The Jawi Peranakan established the Penang Malay Association in 1927 with the expressed aim of promoting the interests of the Malays vis-à-vis the British government. They also played a major role in establishing the Penang state branch of Umno in 1946 with SM Aidid as the founder president.

Business boom

The Tamil Muslims played a significant role in the economic development of Penang during the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century.

They virtually monopolised the shipping and stewarding industry of Penang by providing lighters or tongkangs to load and unload goods from ships to the port.

Many of them worked, ate, and slept in the tongkang, and hence were often referred to as “Mamak Tongkang” (Uncle Tongkang).

The Tamil Muslims also opened provision stores, textile shops, and eateries. Subsequently, they branched out as jewellers, money changers, book publishers and distributors, pharmacists, and bakers.

No historical narrative on our nation’s Tamil Muslim community can be complete without mentioning the iconic “mamak” restaurants that are ubiquitous in cities and towns all over Malaysia. These wildly popular restaurants have become an integral part of our culinary and cultural heritage.

Their offspring were known as “Jawi Pekan” (“town Muslim”) or “Jawi Peranakan” (Indo-Malay community). The number of Jawi Peranakan in Penang increased from 3,491 in 1871 to 5,462 in 1881.

As stated by Helen Fujimoto in her book The South Indian Muslim Community and the Evolution of the Jawi Peranakan in Penang up to 1948 (1989), by the early years of the 20th century, the Jawi Peranakan increasingly identified themselves as Malays.

Indeed, the second and third generations of Jawi Peranakan received scholarships as Malays, entered into the civil service, and served with distinction.

The Jawi Peranakan established the Penang Malay Association in 1927 with the expressed aim of promoting the interests of the Malays vis-à-vis the British government. They also played a major role in establishing the Penang state branch of Umno in 1946 with SM Aidid as the founder president.

Business boom

The Tamil Muslims played a significant role in the economic development of Penang during the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century.

They virtually monopolised the shipping and stewarding industry of Penang by providing lighters or tongkangs to load and unload goods from ships to the port.

Many of them worked, ate, and slept in the tongkang, and hence were often referred to as “Mamak Tongkang” (Uncle Tongkang).

The Tamil Muslims also opened provision stores, textile shops, and eateries. Subsequently, they branched out as jewellers, money changers, book publishers and distributors, pharmacists, and bakers.

No historical narrative on our nation’s Tamil Muslim community can be complete without mentioning the iconic “mamak” restaurants that are ubiquitous in cities and towns all over Malaysia. These wildly popular restaurants have become an integral part of our culinary and cultural heritage.

Totalling about 12,000 and often operating 24/7, “mamak” restaurants serve affordable, much-loved delicacies, including roti canai, mee goreng mamak, nasi kandar, murtabak, and teh tarik, which appeal to Malaysians from all ethnic origins and walks of life.

Among the prominent Tamil Muslim business companies in Malaysia today are the Barkath Group which focuses on food and beverages and is best known for its two famous products: Hacks sweets and Sunquick squash concentrate; Habib Jewels, one of the nation’s premier jewellers; and Dawood Restaurant, a well-known nasi kandar restaurant in George Town, Penang.

To safeguard their business interests, the Tamil Muslims established various trade organisations. The Penang Muslim Merchants Society, comprising merchants who originated from the ports of Nagore and Nagapattinam, was established on April 1, 1912 with S Amin Sahib as the founder president.

Subsequently, the Tamil Muslims originating from Ramnad district, Tamil Nadu, established the Muslim Mahajana Sabha around 1914. Of more recent origin (1993), is the Malaysian Muslim Restaurant Owners Association.

Establishing media organisations

As stated by William Roff in his book The Origins of Malay Nationalism (1967), “Malay journalism, like book publication in Malay, owes its origins very largely” to the Jawi Peranakan community.

The first Malay newspaper in Malaya was the Jawi Peranakkan (The Local Born Muslim) which started publication in 1876 in Singapore. Its first editor was Munsyi Mohd Said Dada Mohiddin, a Penang-born Jawi Peranakan.

Over the next 30 years, no less than 16 Malay-language newspapers were published: seven in Singapore, five in Penang, and four in Perak.

Out of the seven newspapers in Singapore, five were established by the Jawi Peranakan community: Jawi Peranakkan (1876‒95), Sekola Melayu (1888‒93), Nujumul-Fajar, Shamsul-Kamar, and Taman Pengetahuan (1904‒05).

In Penang, all five early newspapers were established by the Jawi Peranakan community: Tanjung Penegeri (1894‒95), Pemimpin Warta (1895‒97), Lengkongan Bulan (1900‒01), Bintang Timor (1900), and Chahaya Pulau Pinang (1900‒08).

Similarly, two of the early Malay newspapers in Perak were established by the Jawi Peranakan: Sri Perak (1893‒95) and Jajahan Melayu (1896‒97).

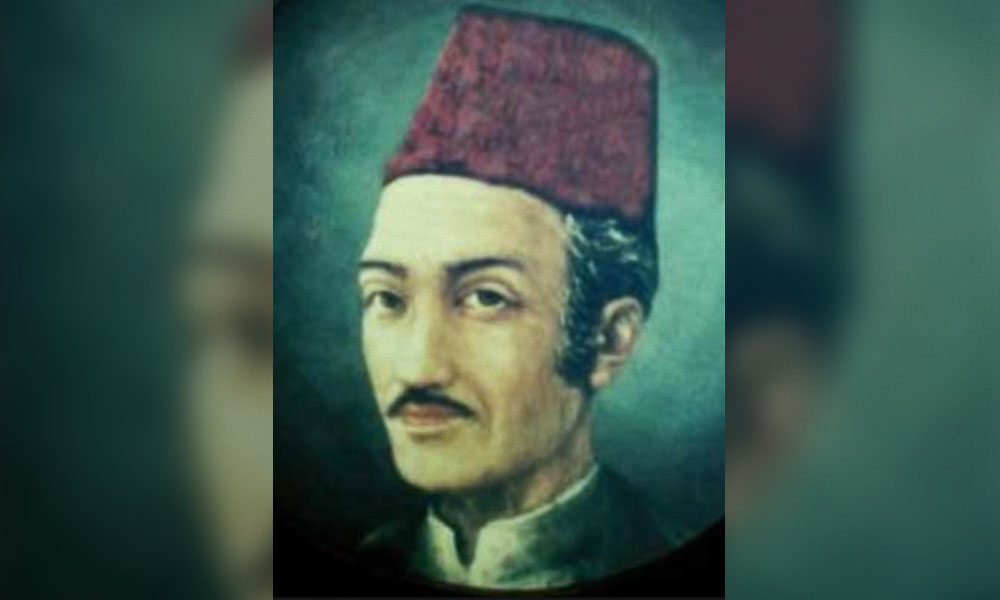

Special mention should be made of Abdullah Abdul Kadir, popularly known as Munshi Abdullah (1796–1854). Of Tamil and Arab (Yemeni) descent, he is widely regarded as the “father of modern Malay literature” and arguably the first Malayan journalist.

Munshi Abdullah

The significance of his main work, Hikayat Abdullah (published in 1849) is best summarised by Encyclopaedia Britannica: “In contrast to the largely court literature of the past, the Hikayat Abdullah provided a lively and colloquial descriptive account of events and people with a freshness and immediacy hitherto unknown.”

Raising mosques

The Tamil Muslims of Penang can also take pride in having established numerous mosques and bequeathing religious endowments.

Of the approximately 67 mosques in Penang (1903), 22 had been established by the Indian Muslims, mainly Tamil Muslims. Probably the mosque with the biggest wakaf property in Malaysia is the Masjid Kapitan Keling built by Cauder Mohideen Merican in 1803.

As stated by Khoo Salma Nasution in her book The Chulia in Penang: Patronage and Place-Making Around the Kapitan Kling Mosque 1786‒1957 (2014), the Tamil Muslims also established the first modern Arabic school in Penang: the Kapitan Kling Mosque’s Madrasah Haniah.

Icons of history

Among the prominent Malaysian Tamil Muslims who have served the nation admirably are Ali Abul Hassan Sulaiman and Hamid Sultan Abu Backer. The former is a well-known economist and the sixth governor of Bank Negara (1998‒2000) while the latter is a fearless and honest retired judge of the Court of Appeal who championed social justice and the rule of law at all times.

Additionally, over a span of 14 years on the bench, Hamid Sultan remarkably wrote more than one thousand judgments on various aspects of the law.

The significance of his main work, Hikayat Abdullah (published in 1849) is best summarised by Encyclopaedia Britannica: “In contrast to the largely court literature of the past, the Hikayat Abdullah provided a lively and colloquial descriptive account of events and people with a freshness and immediacy hitherto unknown.”

Raising mosques

The Tamil Muslims of Penang can also take pride in having established numerous mosques and bequeathing religious endowments.

Of the approximately 67 mosques in Penang (1903), 22 had been established by the Indian Muslims, mainly Tamil Muslims. Probably the mosque with the biggest wakaf property in Malaysia is the Masjid Kapitan Keling built by Cauder Mohideen Merican in 1803.

As stated by Khoo Salma Nasution in her book The Chulia in Penang: Patronage and Place-Making Around the Kapitan Kling Mosque 1786‒1957 (2014), the Tamil Muslims also established the first modern Arabic school in Penang: the Kapitan Kling Mosque’s Madrasah Haniah.

Icons of history

Among the prominent Malaysian Tamil Muslims who have served the nation admirably are Ali Abul Hassan Sulaiman and Hamid Sultan Abu Backer. The former is a well-known economist and the sixth governor of Bank Negara (1998‒2000) while the latter is a fearless and honest retired judge of the Court of Appeal who championed social justice and the rule of law at all times.

Additionally, over a span of 14 years on the bench, Hamid Sultan remarkably wrote more than one thousand judgments on various aspects of the law.

Hamid Sultan Abu Backer

In the field of politics, the late SOK Ubaidulla Kadir Basha played an active role in MIC. He served as the permanent chairperson of MIC and deputy president of the Senate besides being the founding president of the Associated Indian Chambers of Commerce, Malaya (1950‒51) and the Malaysian Islamic Welfare Organisation (1961‒65).

Another prominent Malaysian Tamil Muslim politician is Nor Mohamed Yakcop who served as minister of finance II (2004‒09), Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (2009‒13), and adviser to Bank Negara (1968‒94 and 1998‒2000).

Mention must also be made of SM Mohamed Idris, Malaysia’s pioneering and fearless consumer advocate, and a staunch champion of environmental protection and workers’ rights. He was the longtime president of the Consumers Association of Penang and Sahabat Alam Malaysia.

Summing up, Malaysian Tamil Muslims have made significant contributions towards nation-building since the 15th century when they played a major role in promoting Malacca’s trade.

Subsequently, during the 17th and 18th centuries, they lent their entrepreneurial spirit to develop trade between India and the Malay Peninsula. Of equal significance, the Tamil Muslims who married local Malay women (Jawi Peranakan) pioneered Malay publications.

Continuing to make a substantial impact in the post-independence period up to present times, the Tamil Muslim community has left its lasting imprint – and continues to make notable contributions – in diverse fields such as economic development and civil society activism.

Last but not least, through its unique cultural heritage, the Tamil Muslim community has helped enrich and shape our magnificent multicultural society.

In the field of politics, the late SOK Ubaidulla Kadir Basha played an active role in MIC. He served as the permanent chairperson of MIC and deputy president of the Senate besides being the founding president of the Associated Indian Chambers of Commerce, Malaya (1950‒51) and the Malaysian Islamic Welfare Organisation (1961‒65).

Another prominent Malaysian Tamil Muslim politician is Nor Mohamed Yakcop who served as minister of finance II (2004‒09), Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (2009‒13), and adviser to Bank Negara (1968‒94 and 1998‒2000).

Mention must also be made of SM Mohamed Idris, Malaysia’s pioneering and fearless consumer advocate, and a staunch champion of environmental protection and workers’ rights. He was the longtime president of the Consumers Association of Penang and Sahabat Alam Malaysia.

Summing up, Malaysian Tamil Muslims have made significant contributions towards nation-building since the 15th century when they played a major role in promoting Malacca’s trade.

Subsequently, during the 17th and 18th centuries, they lent their entrepreneurial spirit to develop trade between India and the Malay Peninsula. Of equal significance, the Tamil Muslims who married local Malay women (Jawi Peranakan) pioneered Malay publications.

Continuing to make a substantial impact in the post-independence period up to present times, the Tamil Muslim community has left its lasting imprint – and continues to make notable contributions – in diverse fields such as economic development and civil society activism.

Last but not least, through its unique cultural heritage, the Tamil Muslim community has helped enrich and shape our magnificent multicultural society.

RANJIT SINGH MALHI is an independent historian who has written 19 books on Malaysian, Asian and world history. He is highly committed to writing an inclusive and truthful history of Malaysia based upon authoritative sources.

Significant contributions of M'sian Tamil Muslims.

ReplyDeleteThe biggest contribution was Malaysia's 4th Prime Minister.

Years ago, I knew a doctor, the late Doctor Selva as I called him, who was Mahathir's hostel room-mate when they were studying medicine at King Edward V College of Medicine at the University of Singapore.

Mahathir was Very Indian in those days, culturally and ethnically, with your typical Indian way of speaking and mannerisms, wakakaka....the University of Singapore authorities had categorised him as an Indian, that's how he had been assigned to the same hostel room as Selva.

Only much later, Mahathir became a raging Malay Ethno Supremacist.

He's not a Tamil, not good enough, wakakaka

DeleteIf only the Tamil non-Muslims could emulate these first rate immigrants...

ReplyDeleteFollowing yr mfering steps of palsu-ness!

Delete