Thanks 'MF' - good post:

MF commented on "Netanyahu tells U.S. that Israel will strike Iranian military, not nuclear or oil, targets, officials say"

Take away the carefully cast illusion that Israel is the ancient, Biblically protected state and you are left with nothing but a purposely hyper-militarized surveillance state committing genocidal atrocities.

I’ve written this many times, but it bears reminding as we continue to see Israel commit countless totally ruthless war crimes; the religious Jews are not the same as the Zionists.

There are two Israels. One is the home of religious Jews, the other is the tyrannical Zionist machine hidden behind them.

From its inception, the State of Israel has been a very carefully groomed psyop. If you’re yelling at me right now then you’ve taken the bait and accepted the story you’ve been told.

The spell is being broken so that people can clearly see the reality of the Zionist faction that runs Israel.

They give nothing to the world but subterfuge, chaos, debt and destruction.

The High Table of the Cabal is in Tel Aviv, and the religious Jews there are no less victim than anyone else.

It is not hating Jews to point to those who call themselves Jews to hide criminality. In fact, it is just the opposite. Rooting out the cancer in Israel will provide the religious Jews a chance to actually have a place to call home that is not constantly at odds with its neighbors, and currently, most of the world.

If you believe that the Jews are a covenant people, loved and protected by God, you cannot at the same time want their country to be run by creeps who invite the world to destroy them, daily.

For the religious state to survive, the criminal state must go. Is it really any different than loving America but wanting the criminal element in America’s government removed?

It is the criminals that need to go, no matter what they call themselves.

Israel’s Religiously Divided Society

Deep gulfs among Jews, as well as between Jews and Arabs, over political values and religion’s role in public life

Nearly 70 years after the establishment of the modern State of Israel, its Jewish population remains united behind the idea that Israel is a homeland for the Jewish people and a necessary refuge from rising anti-Semitism around the globe. But alongside these sources of unity, a major new survey by Pew Research Center also finds deep divisions in Israeli society – not only between Israeli Jews and the country’s Arab minority, but also among the religious subgroups that make up Israeli Jewry.

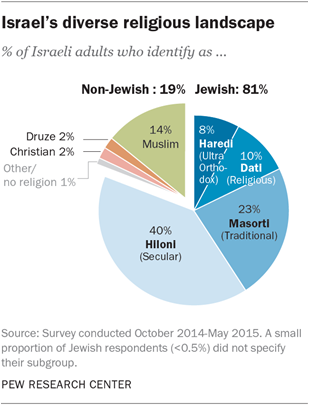

Nearly all Israeli Jews identify with one of four categories: Haredi (commonly translated as “ultra-Orthodox”), Dati (“religious”), Masorti (“traditional”) or Hiloni (“secular”).

Although they live in the same small country and share many traditions, highly religious and secular Jews inhabit largely separate social worlds, with relatively few close friends and little intermarriage outside their own groups. In fact, the survey finds that secular Jews in Israel are more uncomfortable with the notion that a child of theirs might someday marry an ultra-Orthodox Jew than they are with the prospect of their child marrying a Christian. (See Chapter 11 for more information.)

Moreover, these divisions are reflected in starkly contrasting positions on many public policy questions, including marriage, divorce, religious conversion, military conscription, gender segregation and public transportation. Overwhelmingly, Haredi and Dati Jews (both generally considered Orthodox) express the view that Israel’s government should promote religious beliefs and values, while secular Jews strongly favor separation of religion from government policy.

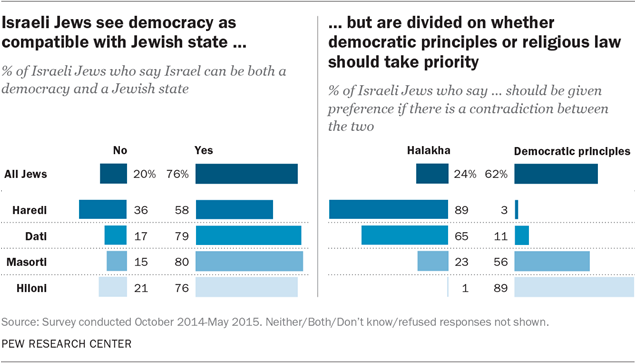

Most Jews across the religious spectrum agree in principle that Israel can be both a democracy and a Jewish state. But they are at odds about what should happen, in practice, if democratic decision-making collides with Jewish law (halakha). The vast majority of secular Jews say democratic principles should take precedence over religious law, while a similarly large share of ultra-Orthodox Jews say religious law should take priority.

Even more fundamentally, these groups disagree on what Jewish identity is mainly about: Most of the ultra-Orthodox say “being Jewish” is mainly a matter of religion, while secular Jews tend to say it is mainly a matter of ancestry and/or culture.

To be sure, Jewish identity in Israel is complex, spanning notions of religion, ethnicity, nationality and family. When asked, “What is your present religion, if any?” virtually all Israeli Jews say they are Jewish – and almost none say they have no religion – even though roughly half describe themselves as secular and one-in-five do not believe in God. For some, Jewish identity also is bound up with Israeli national pride. Most secular Jews in Israel say they see themselves as Israeli first and Jewish second, while most Orthodox Jews (Haredim and Datiim) say they see themselves as Jewish first and then Israeli.

The survey also looks at differences among Israeli Jews based on age, gender, education, ethnicity (Ashkenazi or Sephardi/Mizrahi) and other demographic factors. For example, Sephardim/Mizrahim are generally more religiously observant than Ashkenazim, and men are somewhat more likely than women to say halakha should take precedence over democratic principles. But in many respects, these demographic differences are dwarfed by the major gulfs seen among the four religious subgroups that make up Israeli Jewry.

While most Israelis are Jewish, a growing share (currently about one-in-five adults) belong to other groups. Most non-Jewish residents of Israel are ethnically Arab and identify, religiously, as Muslims, Christians or Druze.1

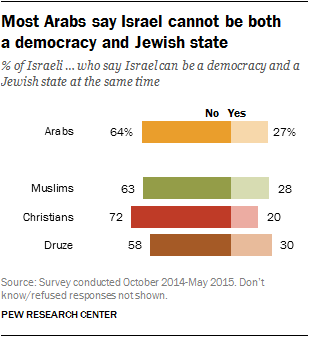

The survey shows that Israeli Arabs generally do not think Israel can be a Jewish state and a democracy at the same time. This view is expressed by majorities of Muslims, Christians and Druze. And overwhelmingly, all three of these groups say that if there is a conflict between Jewish law and democracy, democracy should take precedence.

But this does not mean most Arabs in Israel are committed secularists. In fact, many Muslims and Christians support the application of their own religious law to their communities. Fully 58% of Muslims favor enshrining sharia as official law for Muslims in Israel, and 55% of Christians favor making the Bible the law of the land for Christians.

Roughly eight-in-ten Israeli Arabs (79%) say there is a lot of discrimination in Israeli society against Muslims, who are by far the biggest of the religious minorities. On this issue, Jews take the opposite view; the vast majority (74%) say they do not see much discrimination against Muslims in Israel.

At the same time, Jewish public opinion is divided on whether Israel can serve as a homeland for Jews while also accommodating the country’s Arab minority. Nearly half of Israeli Jews say Arabs should be expelled or transferred from Israel, including roughly one-in-five Jewish adults who strongly agree with this position.

The divisions between Jews and Arabs are also reflected in their views on the peace process. In recent years, Arabs in Israel have become increasingly doubtful that a way can be found for Israel and an independent Palestinian state to coexist peacefully. As recently as 2013, roughly three-quarters of Israeli Arabs (74%) said a peaceful two-state solution was possible. As of early 2015, 50% say such an outcome is possible.

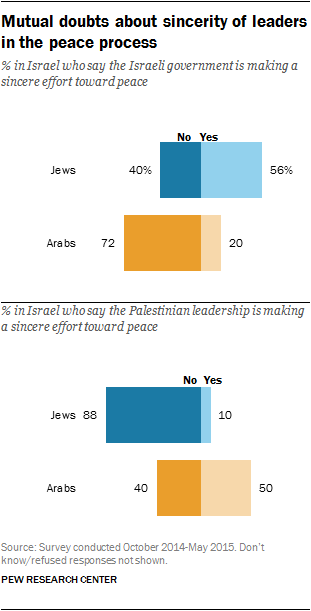

Israeli Arabs are highly skeptical about the sincerity of the Israeli government in seeking a peace agreement, while Israeli Jews are equally skeptical about the sincerity of Palestinian leaders. But there is plenty of distrust to go around: Fully 40% of Israeli Jews say their own government is not making a sincere effort toward peace, and an equal share of Israeli Arabs say the same about Palestinian leaders.

Israel’s major religious groups also are isolated from one another socially. The vast majority of Jews (98%), Muslims (85%), Christians (86%) and Druze (83%) say all or most of their close friends belong to their own religious community.

Jews are more likely than Arabs to say all their friends belong to their religious group. To some extent, this may reflect the fact that the majority of Israel’s population is Jewish. Two-thirds of Israeli Jews (67%) say all of their friends are Jewish. By comparison, 38% of Muslims, 21% of Christians and 22% of Druze say all their friends share their religion.

These are some of the key findings of Pew Research Center’s comprehensive survey of religion in Israel, which was conducted through face-to-face interviews in Hebrew, Arabic and Russian among 5,601 Israeli adults (ages 18 and older) from October 2014 through May 2015. The survey uses the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics’ definition of the Israeli population, which includes Jews living in the West Bank as well as Arab residents of East Jerusalem.

No comments:

Post a Comment