Ooi Kok Hin

Published: Oct 16, 2024 12:20 PM

COMMENT | Ann Teo started her involvement in Sarawak civil society approximately 20 years ago. Whether as a para-counsellor for women in crisis or a legal practitioner, she helped Sarawakians uphold their basic rights and civil liberties.

She taught rural Sarawakians, Penan women and girls, how to deal with harassment and exploitation. During the Bersih rallies in Kuching, she was the chief lawyer defending their rights to peaceful assembly.

In 2016, she and her friends drove 800km from Miri to Kuching mobilising Sarawakians to participate in the Bersih 5 convoy and stand up for electoral and systemic change.

One morning in 2024, however, she found herself in an unusual situation: She was accused of not being “Sarawakian” enough.

It began with some fellow activists and a prominent academic accusing her and the voter education organisation she co-founded (Rose Sarawak) of being “manipulated” by “Malayan NGOs.”

Within days, their rhetoric escalated. Popular media pundit and academic James Chin even tweeted, “These people should move to Malaya!” This insult to a Sarawakian carries the same derogation as “Balik tongsan/Balik India” (Go back to China/Go back to India) to a non-Malay.

Although they did not mention Teo or Rose by name, they were the only individual or organisations that fit the bill given the context of Rose’s work in voter enfranchisement and redelineation.

Why is this happening?

35pct seat demand

At the surface level, it is about Sarawak and Sabah’s demand for 35 percent of seats in Parliament. Proponents have argued that 35 percent representation in Dewan Rakyat is necessary because it guarantees Borneo a veto power to block constitutional amendments that the peninsula could unilaterally pass.

At a deeper level, it is about Sarawak and Sabah’s place in the Federation of Malaysia. After decades of marginalisation, the ground is strong enough to capitalise on Sarawak and Sabah’s newly founded leverage – no longer a fixed deposit, but a kingmaker.

Published: Oct 16, 2024 12:20 PM

COMMENT | Ann Teo started her involvement in Sarawak civil society approximately 20 years ago. Whether as a para-counsellor for women in crisis or a legal practitioner, she helped Sarawakians uphold their basic rights and civil liberties.

She taught rural Sarawakians, Penan women and girls, how to deal with harassment and exploitation. During the Bersih rallies in Kuching, she was the chief lawyer defending their rights to peaceful assembly.

In 2016, she and her friends drove 800km from Miri to Kuching mobilising Sarawakians to participate in the Bersih 5 convoy and stand up for electoral and systemic change.

One morning in 2024, however, she found herself in an unusual situation: She was accused of not being “Sarawakian” enough.

It began with some fellow activists and a prominent academic accusing her and the voter education organisation she co-founded (Rose Sarawak) of being “manipulated” by “Malayan NGOs.”

Within days, their rhetoric escalated. Popular media pundit and academic James Chin even tweeted, “These people should move to Malaya!” This insult to a Sarawakian carries the same derogation as “Balik tongsan/Balik India” (Go back to China/Go back to India) to a non-Malay.

Although they did not mention Teo or Rose by name, they were the only individual or organisations that fit the bill given the context of Rose’s work in voter enfranchisement and redelineation.

Why is this happening?

35pct seat demand

At the surface level, it is about Sarawak and Sabah’s demand for 35 percent of seats in Parliament. Proponents have argued that 35 percent representation in Dewan Rakyat is necessary because it guarantees Borneo a veto power to block constitutional amendments that the peninsula could unilaterally pass.

At a deeper level, it is about Sarawak and Sabah’s place in the Federation of Malaysia. After decades of marginalisation, the ground is strong enough to capitalise on Sarawak and Sabah’s newly founded leverage – no longer a fixed deposit, but a kingmaker.

Teo and Rose made a principled (and brave) objection: the “one-third representation” was never promised in the Malaysia Agreement 1963 (MA63) or the earlier Inter-Governmental Committee (IGC) report.

Borneo only has 17 percent of the electorate but possesses 25 percent of seats in Dewan Rakyat. And now the political parties and some advocates want 35 percent?

This is not right. This is an unbalanced representation (malapportionment). So Teo and Rose joined Bersih, Tindak Malaysia, and Engage to issue a joint statement opposing the 35 percent demand and offering an alternative in the form of 35 percent representation in the Senate.

Then, the name-calling and labelling started.

Intense but civil debate

Last week, I was part of a successful roadshow conducted by Bersih in Kuching that reached over 150 Sarawakian youths and activists. I watched as Teo and the others held court and debated the issue, intense but civil.

Below is a question–and–answer-style exploration of what I observed to be a very important issue, but may not receive the national attention it deserves.

If Borneo’s 35 percent representation demand is not handled well, it could lead to growing ethnoreligious sentiments, the conflict between “Malaya” and Borneo, and even secessionist discourse regarding Borneo’s place in Malaysia.

Why are some in Sarawak and Sabah demanding one-third representation in Parliament?

The demand for one-third of parliamentary seats in the Dewan Rakyat for Sarawak and Sabah is rooted in the belief that such representation would serve as a protective measure for the interests of these Borneo states.

Proponents have argued that having one-third of the seats would effectively give Sarawak and Sabah veto power over national legislation, safeguarding their autonomy.

However, this demand is not based on any explicit provision in the MA63 or the IGC report, which laid the foundation for the formation of Malaysia.

Once confronted with the absence of such a guarantee in the documents, the proponents have now shifted the basis of their argument to the “Spirit of MA63,” which is ambiguous and, well, how do you prove or disprove the existence of a spirit?

Is this demand fair or democratic?

No, the demand for one-third representation in the Dewan Rakyat is undemocratic. Why? Sarawak and Sabah make up roughly 17 percent of Malaysia’s total number of voters.

Granting these states one-third of the parliamentary seats would disproportionately inflate their political power compared to highly populated states in Peninsular Malaysia, such as Selangor and Johor.

This would create an imbalance where a voter in Sarawak or Sabah has significantly more influence than a voter in Peninsular Malaysia.

Thomas Fann, chairperson of Engage, an NGO specialising in delineation research, estimates that if the 35 percent representation is realised, the result is one Sarawak voter has four times the political power of one Selangor voter.

Also, the smallest parliamentary constituency in Malaysia is not Putrajaya but Igan in Sarawak, which has just about 30,000 voters. In comparison, Bangi has over 300,000 voters. Both Igan and Bangi have one seat each, but one MP serves 30,000 constituents and the other MP serves 10 times the population with the same number of resources.

On which planet is this fair and democratic?

But isn’t it true that when Singapore left, the 15 seats held by Singapore were “given” to Malaya? The demand for one-third is to fix this “historical error”.

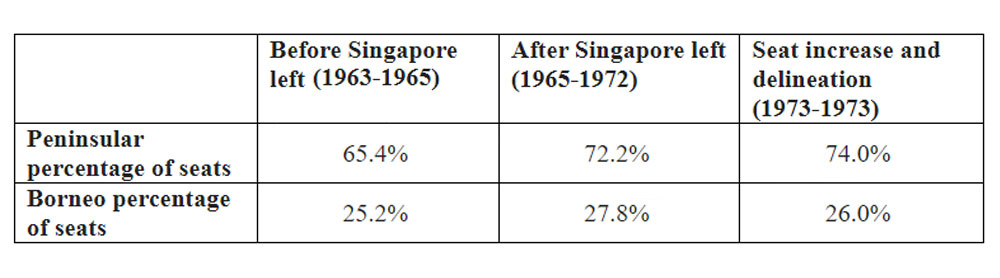

False. When Singapore left, the 15 seats were not “given” to Malaya. The seats simply disappeared with their exit.

Here’s an explanation by Danesh Prakash Chacko, director of Tindak Malaysia, an electoral advocacy group:

Thomas Fann

“When Singapore was expelled in 1965, Dewan Rakyat’s seat count fell to 144. References to 15 seats for Singapore were removed from the constitution. No mention of seats being added to the states of Malaya.

“In 1967/68, the redelineation of the states of Malaya took place and no new seats were added throughout this period.” My addition: if the Singapore seats were indeed given to Malaya, it would have been done in the 1967/68 delineation. It didn’t!”

Danesh continues, “In 1973, constitutional amendments increased Dewan Rakyat’s size to 154. All 10 new seats were found in Peninsular Malaysia. No concurrent increase for Sabah and Sarawak.”

So 10 new seats were created in 1973 delineation and all of them were found in Malaya. Why did Sabahan and Sarawakian MPs pass this constitutional amendment? Why weren’t they outraged?

The answer is simple: after Singapore left, Sarawak and Sabah’s proportion of seats in the federation actually increased from 25.2 percent to 27.8 percent. The 1973 delineation which added 10 seats to Peninsular Malaysia reduced Borneo’s percentage to 26 percent, which is still higher than their pre-1965 share.

“When Singapore was expelled in 1965, Dewan Rakyat’s seat count fell to 144. References to 15 seats for Singapore were removed from the constitution. No mention of seats being added to the states of Malaya.

“In 1967/68, the redelineation of the states of Malaya took place and no new seats were added throughout this period.” My addition: if the Singapore seats were indeed given to Malaya, it would have been done in the 1967/68 delineation. It didn’t!”

Danesh continues, “In 1973, constitutional amendments increased Dewan Rakyat’s size to 154. All 10 new seats were found in Peninsular Malaysia. No concurrent increase for Sabah and Sarawak.”

So 10 new seats were created in 1973 delineation and all of them were found in Malaya. Why did Sabahan and Sarawakian MPs pass this constitutional amendment? Why weren’t they outraged?

The answer is simple: after Singapore left, Sarawak and Sabah’s proportion of seats in the federation actually increased from 25.2 percent to 27.8 percent. The 1973 delineation which added 10 seats to Peninsular Malaysia reduced Borneo’s percentage to 26 percent, which is still higher than their pre-1965 share.

Nothing was taken from Sarawak and Sabah. Borneo’s share of parliamentary seats remains remarkably consistent: 25.2 percent in 1963, and also 25.2 percent in 2024.

And nothing was written in the IGC report that if Singapore (or any entity) were to leave, their share must be redistributed among Sarawak and Sabah. The demand for 35 percent representation is not a restoration to the historical past, but a departure from it.

Borneo leaders did not demand more seats in the 1973 exercise because they were satisfied with holding the line, not extending their gains. The IGC report merely stated that Borneo seats could not be reduced within seven years, so they were satisfied that their seats weren’t reduced in the 1973 delineation.

The view that “15 Singapore seats must be redistributed to Sarawak and Sabah” is a modern interpretation retrospectively applied to a historical event, not a historical error as claimed by some.

If not, why did Ling Beng Siew of Sarawak and Mustapha Harun of Sabah vote yes for the 1966 amendment, and Jugah Barieng of Sarawak vote yes for the 1973 amendment - all of whom are the signatories of the MA63 representing Sabah and Sarawak? (thanks to researcher Wo Chang Xi for discovering this fact)

If the myth of “15 Singapore seats” is indeed a historical error, why did the signees of MA63 not only not feel a sense of injustice, but participated in passing the above constitutional amendment?

No way that any of this is true. Isn’t one-third of representation explicitly written in MA63 and the IGC?

Find the documents, judge for yourself, and claim your prize! During a public forum by Bersih on Aug 30, 2024, political scientist Wong Chin Huat offered RM10,000 for anyone who could find proof to support the 35 percent inheritance claim in MA63.

But Chin argued that malapportionment is just a Malay-Chinese issue in Peninsular Malaysia. Don’t bring your “Malayan” problems into Borneo!

Is this James Chin, or Abdul Hadi Awang? Nine out of the 20 largest parliamentary constituencies have either a Malay majority or plurality.

This does not stop far-right conservatives from framing malapportionment as an ethnic or even religious issue that could “erode Malay power.” For them, urban voters and Chinese voters are interchangeable.

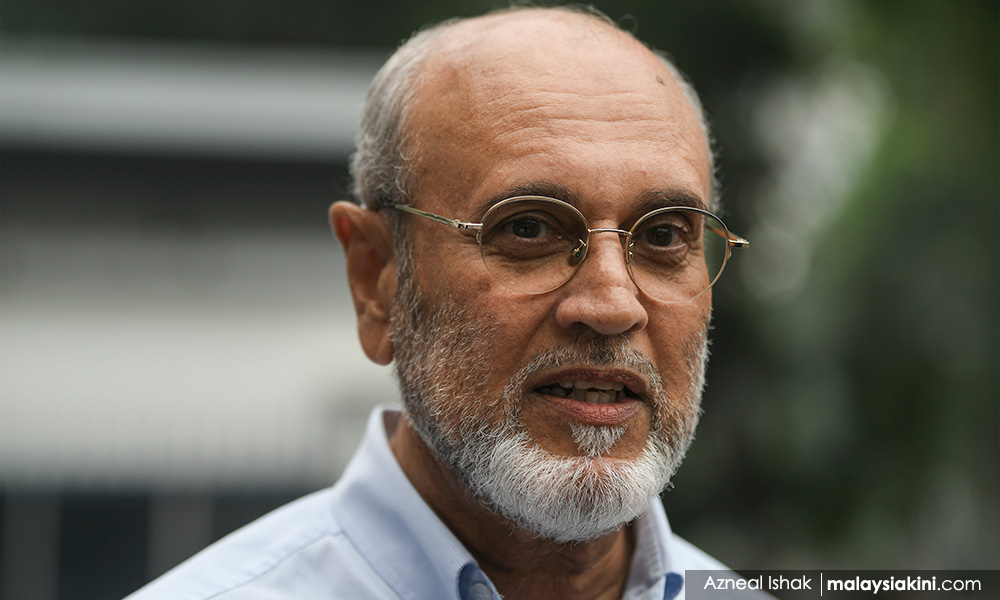

James Chin

But this is increasingly untrue due to rapid urbanisation and low birth date of the non-Malays. Many under-represented urban areas are now Malay-majority seats, with urban Malays being victims of malapportionment too. We should avoid amplifying the “Malay vs non-Malay” ethnic framing of this issue.

While malapportionment is a more pronounced issue in Peninsular Malaysia, where rural constituencies often have far fewer voters than urban ones, this problem exists in Sarawak and Sabah too.

The idea that malapportionment is a “Malayan problem” reflects a misunderstanding of the issue. Electoral imbalances affect the whole federation, including Sarawak where Miri has over 140,000 voters while Igan has 30,000 voters.

As Wong said, “Malapportionment is excessive even within inland Sarawak. Baram - of a similar size to Perak - had 60,107 voters, more than twice of 28,501 voters in Igan, which is less than half of Negeri Sembilan in landmass.”

Is malapportionment still a “Malayan” issue?

Malapportionment is not a race issue or a Malayan issue. With urbanisation and the Undi18 constitutional amendment, it is a national issue that affects all, especially youth voters.

Young voters who work or study in urban areas are massively under-represented. The framing of malapportionment in ethno-religious terms is not only divisive but also distracts from the real issue of fair and democratic representation.

Bersih chairperson Muhammad Faisal Abdul Aziz said it most effectively: “Will we support 35 percent representation for Borneo if there is no interstate and intrastate malapportionment? Yes. Can we still support 35 percent representation for Borneo given pre-existing malapportionment? No.”

But this is increasingly untrue due to rapid urbanisation and low birth date of the non-Malays. Many under-represented urban areas are now Malay-majority seats, with urban Malays being victims of malapportionment too. We should avoid amplifying the “Malay vs non-Malay” ethnic framing of this issue.

While malapportionment is a more pronounced issue in Peninsular Malaysia, where rural constituencies often have far fewer voters than urban ones, this problem exists in Sarawak and Sabah too.

The idea that malapportionment is a “Malayan problem” reflects a misunderstanding of the issue. Electoral imbalances affect the whole federation, including Sarawak where Miri has over 140,000 voters while Igan has 30,000 voters.

As Wong said, “Malapportionment is excessive even within inland Sarawak. Baram - of a similar size to Perak - had 60,107 voters, more than twice of 28,501 voters in Igan, which is less than half of Negeri Sembilan in landmass.”

Is malapportionment still a “Malayan” issue?

Malapportionment is not a race issue or a Malayan issue. With urbanisation and the Undi18 constitutional amendment, it is a national issue that affects all, especially youth voters.

Young voters who work or study in urban areas are massively under-represented. The framing of malapportionment in ethno-religious terms is not only divisive but also distracts from the real issue of fair and democratic representation.

Bersih chairperson Muhammad Faisal Abdul Aziz said it most effectively: “Will we support 35 percent representation for Borneo if there is no interstate and intrastate malapportionment? Yes. Can we still support 35 percent representation for Borneo given pre-existing malapportionment? No.”

Muhammad Faisal Abdul Aziz

What could possibly be the worst outcome if Borneo is given 35 percent representation in Dewan Rakyat? It can’t be that bad.

Imagine this: Umno-BN lost in the 14th general election, but Najib Abdul Razak remains the prime minister. Rosmah’s boxes of jewellery and handbags were never photographed. Najib was never held accountable or jailed for the 1MDB scandal.

None of that ever happened because if Borneo had 35 percent of parliamentary seats and if Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu Sarawak, Sabah Umno, and their allies had full control of the enlarged 60-80 seats, they would have come to Najib’s rescue then.

Under an enlarged Dewan Rakyat with 35 percent Borneo representation, Wong calculated that a federal government could be formed with only 35 percent MPs from Borneo, plus a mere 16 percent MPs from Peninsular Malaysia. Popular votes be damned.

Is this a “Borneo vs Malaya” issue?

There is a concerted effort to drive us towards a path of conflict between Borneo and peninsula states. Chin even wrote to Malaysiakini stating that “Malayan NGOs” are acting like colonial masters.

But we should resist this dichotomy. Not all residents of Sarawak and Sabah support these ideas and not all residents of “Malaya” oppose this idea.

What is happening is simply intolerance. Non-Bornean critics are not permitted to criticise their plan for 35 percent representation because we are not regarded as one of them, while Bornean critics are dismissed as “being manipulated” or "traitors.” Does that remind you of a far-right cult?

As representation in Parliament is a matter of national importance, all citizens of Malaysia are stakeholders in this issue and have the locus standi to support or criticise this proposal.

How about the argument that the 35 percent Borneo representation can act as a veto against Islamisation policies?

Some non-Malay Malayans are inclined to support the 35 percent representation because they believe that the Borneo bloc can act as a veto power against Islamisation.

What could possibly be the worst outcome if Borneo is given 35 percent representation in Dewan Rakyat? It can’t be that bad.

Imagine this: Umno-BN lost in the 14th general election, but Najib Abdul Razak remains the prime minister. Rosmah’s boxes of jewellery and handbags were never photographed. Najib was never held accountable or jailed for the 1MDB scandal.

None of that ever happened because if Borneo had 35 percent of parliamentary seats and if Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu Sarawak, Sabah Umno, and their allies had full control of the enlarged 60-80 seats, they would have come to Najib’s rescue then.

Under an enlarged Dewan Rakyat with 35 percent Borneo representation, Wong calculated that a federal government could be formed with only 35 percent MPs from Borneo, plus a mere 16 percent MPs from Peninsular Malaysia. Popular votes be damned.

Is this a “Borneo vs Malaya” issue?

There is a concerted effort to drive us towards a path of conflict between Borneo and peninsula states. Chin even wrote to Malaysiakini stating that “Malayan NGOs” are acting like colonial masters.

But we should resist this dichotomy. Not all residents of Sarawak and Sabah support these ideas and not all residents of “Malaya” oppose this idea.

What is happening is simply intolerance. Non-Bornean critics are not permitted to criticise their plan for 35 percent representation because we are not regarded as one of them, while Bornean critics are dismissed as “being manipulated” or "traitors.” Does that remind you of a far-right cult?

As representation in Parliament is a matter of national importance, all citizens of Malaysia are stakeholders in this issue and have the locus standi to support or criticise this proposal.

How about the argument that the 35 percent Borneo representation can act as a veto against Islamisation policies?

Some non-Malay Malayans are inclined to support the 35 percent representation because they believe that the Borneo bloc can act as a veto power against Islamisation.

Dennis Ignatius

This view was shared by the respected former Malaysian ambassador Dennis Ignatius. Dennis wrote:

“Ensuring that the Borneo states have veto power over constitutional amendments that may go against the spirit of MA63 is now the last hope we have of maintaining what’s left of the secular democratic nation that came into being in 1963.”

I have sympathies for this argument, but there is no evidence that Sarawak and Sabah leaders ever exercised their leverage to deter, reduce, or pre-empt Islamisation. At most, Gabungan Parti

Sarawak leaders have said, “We will not allow hudud in Sarawak.” They are content with containing Islamisation within Peninsular Malaysia, not confronting or undoing it.

Did Johari or Sabah Chief Minister Hajiji Noor ever say they would direct their MPs to oppose the hudud bill or the mufti bill? The proof is in the pudding…

I hope I am wrong, but some of Borneo’s leaders cite Islamisation not so much as an excuse to save the federation from Islamisation, but to break it apart.

In a recent joint statement released by a group of east Malaysian NGOs, citing the erosion of the secular system, as well as the denial of 35 percent of seats in the Dewan Rakyat, the group outright called for secession.

This view was shared by the respected former Malaysian ambassador Dennis Ignatius. Dennis wrote:

“Ensuring that the Borneo states have veto power over constitutional amendments that may go against the spirit of MA63 is now the last hope we have of maintaining what’s left of the secular democratic nation that came into being in 1963.”

I have sympathies for this argument, but there is no evidence that Sarawak and Sabah leaders ever exercised their leverage to deter, reduce, or pre-empt Islamisation. At most, Gabungan Parti

Sarawak leaders have said, “We will not allow hudud in Sarawak.” They are content with containing Islamisation within Peninsular Malaysia, not confronting or undoing it.

Did Johari or Sabah Chief Minister Hajiji Noor ever say they would direct their MPs to oppose the hudud bill or the mufti bill? The proof is in the pudding…

I hope I am wrong, but some of Borneo’s leaders cite Islamisation not so much as an excuse to save the federation from Islamisation, but to break it apart.

In a recent joint statement released by a group of east Malaysian NGOs, citing the erosion of the secular system, as well as the denial of 35 percent of seats in the Dewan Rakyat, the group outright called for secession.

Signed by prominent activists such as Borneo’s Plight in Malaysia Foundation president Daniel John Jambun, Sabah Sarawak Rights Australia New Zealand president Robert Pei, Saya Anak Sarawak founder Peter John Jaban, Republic Sabah North Borneo president Mosses Paul Anap Ampang, Parti Bumi Kenyalang president Voon Lee Shan, and Gabungan Orang Asal Sabah Sarawak Dayak cultural ambassador Themothy Jagak, the statement read:

“We are no longer bound by the terms of MA63. We demand that the Sabah and Sarawak governments immediately defend our rights and pursue our rightful exit from this failed federation without delay.”

But don’t Sarawak or Sabah have the right to self-determination?

While I personally do not support the idea of these states seceding, I defend the right of Malaysian citizens to advocate for or against it peacefully and democratically. Nation-states are not a Catholic marriage! People should have the right to determine whether to join, stay, or leave a political union.

However, this secessionist discourse mustn’t be conflated with the demand for 35 percent representation.

They are two separate questions, but I can see now why some individuals viciously attack any alternative proposal that offers a balanced pathway that enhances the autonomy of Sarawak and Sabah while keeping them within the federation of Malaysia.

It gets in the way of their plan to stir up the Borneo versus Malaya conflict, and a constructive dialogue with sensible, middle-of-the-road solutions undermines their deep-seated desire to take Sarawak and Sabah out of Malaysia.

Is there an alternative to the one-third representation proposal?

Yes, one compelling alternative is to allocate 35 percent representation for Borneo in the Senate, not the Dewan Rakyat. It is not uncommon for countries like the US to allocate more state-based representation in the upper house and let the lower house be based on population size.

If the proponents truly want veto power, 35 percent representation in the Senate can achieve that because constitutional amendments must pass through both the Dewan Rakyat and Dewan Negara.

Parliament building

This proposal of 35 percent Borneo representation in Dewan Negara put forth by Projek Sama is more realistic, less contentious politically, and can be achieved before GE16.

Critics have pointed out that the Senate, as it exists today, is largely a “paper tiger” because it can only delay a bill’s passage by a maximum of a year before it is sent for royal assent.

The next logical steps are clear then: first, give 35 percent representation to Sarawak and Sabah in the Senate; second, introduce elections for senators in the Dewan Negara so that they have the people’s mandate to introduce or block bills.

Another veto mechanism was brought by Jordan Soo, lawyer and founder of Amali Research, a think tank that specialises in analysing Sarawak government policy.

Soo argued that Article 161(E) can be amended such that any constitutional amendments affecting Sarawak and Sabah must also receive a two-thirds majority in their respective state legislatures.

Surely this should be a welcome proposal by all who seek to enable Borneo’s ability to block unilateral “bulldozing” by Putrajaya.

What are the risks of polarisation and misinformation if we cannot discuss and debate this issue civilly and rigorously?

The risk of polarisation is real. The path forward lies in finding ways to engage in rigorous, even intense, civil discourse.

Drop the name-calling and labelling, and engage in substantive debates to provide roadmaps that empower Borneo and at the same time preserve the federation.

This proposal of 35 percent Borneo representation in Dewan Negara put forth by Projek Sama is more realistic, less contentious politically, and can be achieved before GE16.

Critics have pointed out that the Senate, as it exists today, is largely a “paper tiger” because it can only delay a bill’s passage by a maximum of a year before it is sent for royal assent.

The next logical steps are clear then: first, give 35 percent representation to Sarawak and Sabah in the Senate; second, introduce elections for senators in the Dewan Negara so that they have the people’s mandate to introduce or block bills.

Another veto mechanism was brought by Jordan Soo, lawyer and founder of Amali Research, a think tank that specialises in analysing Sarawak government policy.

Soo argued that Article 161(E) can be amended such that any constitutional amendments affecting Sarawak and Sabah must also receive a two-thirds majority in their respective state legislatures.

Surely this should be a welcome proposal by all who seek to enable Borneo’s ability to block unilateral “bulldozing” by Putrajaya.

What are the risks of polarisation and misinformation if we cannot discuss and debate this issue civilly and rigorously?

The risk of polarisation is real. The path forward lies in finding ways to engage in rigorous, even intense, civil discourse.

Drop the name-calling and labelling, and engage in substantive debates to provide roadmaps that empower Borneo and at the same time preserve the federation.

Allocating greater representation to Borneo, strengthening the Senate, addressing malapportionment, decentralising powers, and fostering dialogue that is free of divisive rhetoric are key steps in this direction.

Where can we start? Should we have a public debate on this issue of 35 percent representation for Borneo and the broader existential questions about the federation of Malaysia?

Yes, this is a topic worth our time. Bersih completed a very well-attended public forum in Kuching on the issue and people are clearly wanting more.

Subsequently, Bersih called for a public debate between two academics who have been providing intellectual arguments for and against the representation: Wong and Chin.

The debate should be put together by a neutral organisation or host to be jointly agreed upon by the two speakers.

Thus, the issue of sincerity does not arise. It’s a simple question to the debate: yes or no? I call on the two intellectuals to take up the debate call and present their views to the public. Sila debat, jangan lari (please debate, don’t run).

What happened to Teo and Rose now?

Teo will persevere, as she always has, despite detractors. Let’s hope more sensible voices like Teo’s will emerge and not be cowed by a culture of fear and intolerance.

If you would like to support Teo and Rose (now spearheaded by a new generation of leadership in Geoffrey Tang), follow and support their work on the Sarawak Rose Facebook page.

OOI KOK HIN is a political sociologist who dabbles in civil society.

No comments:

Post a Comment