COMMENT | What’s wrong with Pakatan Harapan? This is one question that can beg dozens of answers, some complementary while others contradictory. Here is mine, for your consideration alongside those that put heavy emphasis on personalities and communalism.

As this is not answering “what’s right with Harapan”, I will not list its achievements. Don’t misconstrue that Harapan has achieved nothing or complain that this does not do it justice.

In hindsight, nearly four years after GE14, Harapan’s fundamental failure is its inability to understand, steer, and adapt to political transformation.

This failure contributed to its fall in the Sheraton Move but more damagingly, disables it from making a comeback after Sheraton.

Handicaps as a product of history

Many are disappointed with Harapan’s performance in its brief 22 months in power but such disappointment, while legitimate, must be examined against this question: how likely can any first non-Umno government do better?

Could Harapan appoint a better cabinet with more experienced and competent ministers? Difficult. A parliamentary system requires most ministers to be appointed from among MPs and party hierarchy matters.

Unless our Parliament had many parliamentary committees for opposition MPs (and for that matter, backbenchers) and the opposition had a shadow cabinet for its senior MPs to develop policy expertise, how do you expect most first-time ministers to perform excellently?

(The same applies to some incompetent first-term ministers under ex-premier Muhyiddin Yassin and current premier Ismail Sabri Yaakob.)

Could Harapan avoid over-promising in its manifesto? Difficult. Without actual experience in the federal government and shadow ministers to think through policy solutions, how could the opposition produce a manifesto that is both exciting and realistic?

(This defence however cannot be used by Harapan in GE15.)

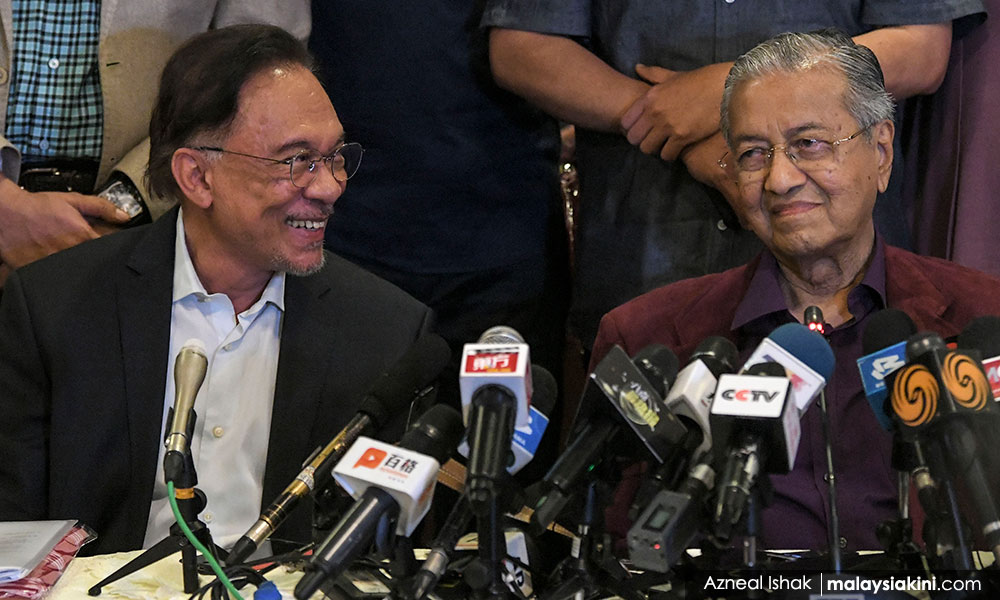

PKR president Anwar Ibrahim (left) and former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad

Could Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Anwar Ibrahim, and Azmin Ali not engage in a power struggle? Yes but only if they were angels or saints.

Could Harapan not pick Mahathir as its prime minister candidate to avoid the subsequent fallout? Yes, but then it might not have won enough Malay votes to oust Umno. Just look at how Harapan lost in Malacca and Johor to grasp this point.

Could Harapan handle ethno-religious relations better, with more tact, humility, and caution? Yes. Would that be enough to stop Umno and PAS from playing up Malay anxiety? No.

Asking the above questions is important because we need to separate what might be inevitable for any first non-Umno government from what Harapan could have done better.

Harapan is a product of history with its handicaps and limitations. To demand perfection is to say BN-Umno’s excesses should be tolerated no matter what. But this is not a blank cheque to excuse Harapan’s mistakes both in and out of power.

Mistake 1: Nasty opposition could be broken up and eliminated

In GE14, Harapan-Warisan won only 48 percent of votes, as the remaining 51 percent largely split between BN (33 percent) and PAS (17 percent).

The victory was made possible by two factors, the Umno-PAS split of Malay votes and the record-high Chinese turnout. As both might not repeat in GE15, many Harapan politicians feared that they would be only a “one-term government”.

What were the their options to this danger?

The first was to break up and eliminate the nasty opposition. Since BN had built up excessive incumbent advantages – in constituency allocation, parliamentary business, selective prosecution/impunity – against the opposition, use them on the new opposition to weaken their base and induce their collapse.

The second would be the exact opposite – levelling the playing field through parliamentary reform, equal constituency allocation, decentralisation, electoral system reform, and reform of the Attorney-General’s Chambers and MACC.

These reforms – some were later implemented under the MOU - would allow the opposition to survive and compete healthily on bread-and-butter issues and integrity, without necessarily playing up ethno-religious issues.

By reducing incumbent advantages, the second option was at least insurance. If Harapan loses Putrajaya in GE15, it may still retain many states and Umno cannot rebuild a corrupt one-party state.

Of course, the second option was not pursued, perhaps never seriously contemplated. Many Harapan leaders and supporters simply saw BN-Umno and PAS as corrupt and racist.

For many self-acclaimed realists, politics must be winner-takes-all. Incentivising the opposition to behave benignly is simply naïve and stupid.

What’s the outcome of Option 1? Harapan increased its parliamentary seats from 121 to 139 (despite losing the Tanjung Piai seat in a by-election), just nine seats short of a two-thirds parliamentary majority.

Harapan gained a total of 15 MPs from BN, 13 of them Umno defectors who ended up in Bersatu. In addition, BN also lost Sarawak BN (now GPS) and PBS which went independent with 19 and one seat respectively.

However, without the constraint of East Malaysians, Umno’s natural response was to team up with PAS in Muafakat Nasional, which constantly accused Harapan as the enemy and traitor of Malays.

Could Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Anwar Ibrahim, and Azmin Ali not engage in a power struggle? Yes but only if they were angels or saints.

Could Harapan not pick Mahathir as its prime minister candidate to avoid the subsequent fallout? Yes, but then it might not have won enough Malay votes to oust Umno. Just look at how Harapan lost in Malacca and Johor to grasp this point.

Could Harapan handle ethno-religious relations better, with more tact, humility, and caution? Yes. Would that be enough to stop Umno and PAS from playing up Malay anxiety? No.

Asking the above questions is important because we need to separate what might be inevitable for any first non-Umno government from what Harapan could have done better.

Harapan is a product of history with its handicaps and limitations. To demand perfection is to say BN-Umno’s excesses should be tolerated no matter what. But this is not a blank cheque to excuse Harapan’s mistakes both in and out of power.

Mistake 1: Nasty opposition could be broken up and eliminated

In GE14, Harapan-Warisan won only 48 percent of votes, as the remaining 51 percent largely split between BN (33 percent) and PAS (17 percent).

The victory was made possible by two factors, the Umno-PAS split of Malay votes and the record-high Chinese turnout. As both might not repeat in GE15, many Harapan politicians feared that they would be only a “one-term government”.

What were the their options to this danger?

The first was to break up and eliminate the nasty opposition. Since BN had built up excessive incumbent advantages – in constituency allocation, parliamentary business, selective prosecution/impunity – against the opposition, use them on the new opposition to weaken their base and induce their collapse.

The second would be the exact opposite – levelling the playing field through parliamentary reform, equal constituency allocation, decentralisation, electoral system reform, and reform of the Attorney-General’s Chambers and MACC.

These reforms – some were later implemented under the MOU - would allow the opposition to survive and compete healthily on bread-and-butter issues and integrity, without necessarily playing up ethno-religious issues.

By reducing incumbent advantages, the second option was at least insurance. If Harapan loses Putrajaya in GE15, it may still retain many states and Umno cannot rebuild a corrupt one-party state.

Of course, the second option was not pursued, perhaps never seriously contemplated. Many Harapan leaders and supporters simply saw BN-Umno and PAS as corrupt and racist.

For many self-acclaimed realists, politics must be winner-takes-all. Incentivising the opposition to behave benignly is simply naïve and stupid.

What’s the outcome of Option 1? Harapan increased its parliamentary seats from 121 to 139 (despite losing the Tanjung Piai seat in a by-election), just nine seats short of a two-thirds parliamentary majority.

Harapan gained a total of 15 MPs from BN, 13 of them Umno defectors who ended up in Bersatu. In addition, BN also lost Sarawak BN (now GPS) and PBS which went independent with 19 and one seat respectively.

However, without the constraint of East Malaysians, Umno’s natural response was to team up with PAS in Muafakat Nasional, which constantly accused Harapan as the enemy and traitor of Malays.

This, and the bourgeoning relationship between Bersatu with Umno defectors that exacerbated the Mahathir-Anwar conflict, ended Harapan.

As executive dominance, centralisation, and patronage politics remained intact, Harapan subsequently lost six state governments through defection.

Mistake 2: ‘Counter-coups’ by defection could be possible

The fear of facing GE15 without incumbent advantages led Harapan to obsessively chase after any chance of regaining power by a ‘counter-coup’ with government MP defections.

While Anwar’s “strong, formidable, and convincing” majority has become a defining joke of his desperation, the obsession was shared throughout all Harapan-plus parties.

In fact, many blamed Anwar, not for pursuing ‘counter-coups’, but for failing to deliver.

Realistically, how could the “counter-coups” be successful and sustainable? Why would Umno parliamentarians topple a non-Umno PM from Bersatu to install a non-Umno PM from Harapan, as they would bound to be punished by Umno grassroots in GE15?

In Warisan president Mohd Shafie Apdal’s case, why would GPS install a prime minister from Sabah and miss their own chance?

And if a Harapan 2.0 government counts on the support of Umno’s court cluster, would it not be punished by its own base, who are more reformist and independent-minded?

What kind of “realists” would fantasise that Umno would hand over Malacca instead of going to the polls?

Haunted by the fear of losing GE15 and possessed by an addiction to incumbent advantages, Harapan wasted every day post-Sheraton.

It refused to focus on governance and form a shadow cabinet to ‘mark’ (as in football) ministers. Most tellingly, they could not table a shadow budget in 2020 after losing power, which it successfully did for seven years before winning power in 2018.

In a crisis is danger and opportunity, but a directionless Harapan failed to turn the government’s crises into its own opportunities.

When the Muhyiddin government failed on the pandemic, no one saw a successful alternative in Harapan. When Ismail Sabri’s federal government failed on the floods, no one said Harapan’s Selangor state government was a success.

Mistake 3: Voters can still be mobilised by anger

Harapan’s failure to offer superior and workable alternatives is caused by its addiction to both incumbent advantages and anger mobilisation.

The “Anything but Umno” (ABU) anger – the term coined around 2008 but the sentiment existed the latest since 1990 – was simply resurrected as a rejection of “backdoor governments” after Sheraton.

The latest resurfaced label is “big tent”, the strategy that brought Harapan and Mahathir together for GE14.

What Harapan failed to realise is that for many voters, anger has simply been disabled by fatigue. They may remain angry and distrustful of BN and Perikatan Nasional (PN), but they have joined the largest party in town – Parti Aku Tak Undi (Patu).

Increasingly, voters will not respond to anger mobilisation for three reasons.

First, it makes them feel stupid when leaders realign rapidly. In Malacca, Harapan simply had no qualms taking Umno frogs after claiming victim to party-hopping.

Second, after Harapan’s 22 months, voters get realistic on what a new government can offer. Third, more than venting their anger on parties and politicians, voters want solutions when crises hit them.

Don’t recycle the pre-2018 playbook

Malaysia’s elections are now in transition into a multi-bloc competition, which may be stable or chaotic. Umno wants to restore the pre-2018 past.

To stop BN, Harapan must recognise the new realities and resist the temptation of recycling the pre-2018 playbook.

WONG CHIN HUAT is an Essex-trained political scientist working on political institutions and group conflicts. Mindful of humans' self-interest motivation while pursuing a better world, he is a principled opportunist.

No comments:

Post a Comment