Murray Hunter

Malaysia’s Two-Speed Economy: Capitalism in the Streets, Scandinavia in the Mind

Samirul Ariff Othman

Jun 24, 2025

Here’s the thing about Malaysia: it runs a free-market economy on paper but manages it like a welfare state in practice. That might have worked in the ‘90s, when oil was abundant, China was just opening up, and the region was still figuring out the rules of globalization. But in today’s world—where capital is faster than policy, and investors have more choices than ever—this contradiction is catching up with us. Fast.

Malaysia likes to pitch itself as an open, investor-friendly, export-driven economy. And in many ways, it is. The country boasts a liberal trade regime, active participation in global value chains, and an economic blueprint—through initiatives like the National Investment Aspirations (NIA)—that speaks the language of innovation, high-value manufacturing, and digital transformation. In fact, if you judged Malaysia solely by its pitch decks and policy documents, you’d think it was ready to compete with Singapore and South Korea.

But scratch beneath the surface, and another reality emerges. It’s a country where the average citizen expects heavily subsidized fuel, free healthcare, near-universal student loans, and affordable toll roads. It’s a system where price controls are routine, affirmative action is permanent, and any attempt to remove subsidies sparks political panic. It’s capitalism in design—but with Scandinavian expectations on a middle-income budget.

This is Malaysia’s real competitiveness conundrum. We want the growth rates of Vietnam and the stability of Singapore, but without giving up the comfort of legacy entitlements. We want to attract the world’s top investors—but with a labour market that’s distorted by outdated quotas, low skills, and a civil service still seen as the ultimate employment safety net. And in a world where investors are voting with their feet, that duality is becoming a liability.

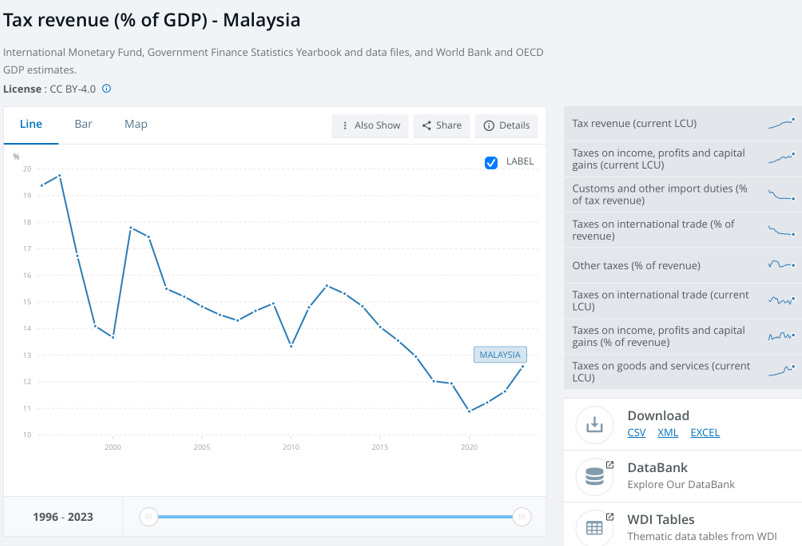

The cost of this split personality is growing. Malaysia’s tax base remains dangerously low—around 11–12% of GDP—yet public expectations for social spending keep climbing. The government is stuck playing fiscal Whac-A-Mole: plugging holes with subsidies, bailouts, and short-term relief schemes, while strategic investments in education, digital infrastructure, and healthcare struggle to get the funding they need. Meanwhile, the middle class—once the quiet engine of Malaysia’s rise—is being squeezed. Wages are stagnating, housing is unaffordable, and upward mobility feels more like a memory than a promise.

This tension has led to reform paralysis. Every government promises structural change. Few survive long enough to deliver it. Any move to rationalize subsidies or shift affirmative action towards needs-based targeting is met with resistance—not just from entrenched interests, but from a public that’s been conditioned to see the state as provider-of-last-resort. We’ve created a political economy that punishes long-term thinking and rewards short-term cushioning.

But here’s the real kicker: Malaysia can’t afford this model anymore. Not with an ageing population. Not with declining oil revenues. Not with Vietnam, Indonesia, and even the Philippines pulling ahead in investor rankings. The global economy isn’t slowing down to wait for us. It’s moving to where the rules are clear, the talent is agile, and the institutions don’t get reshuffled every 18 months.

So what’s the path forward?

Malaysia needs a reality check—and a reset. We need to decide, as a country, whether we’re serious about being a competitive, innovation-led economy—or whether we’ll remain trapped in a halfway house between entitlement and enterprise. That means shifting from blanket subsidies to targeted protection. It means reforming taxation, upgrading education, and aligning our labour policies with the needs of a 21st-century economy. And most of all, it means leveling with the public: you can’t have Swedish services on a Malaysian budget without paying for them.

The truth is, Malaysia didn’t fall behind because others cheated. It fell behind because it refused to choose. And in a world that increasingly rewards clarity, discipline, and courage, indecision is the most expensive policy of all.

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GC.TAX.TOTL.GD.ZS?locations=MY

Economist Samirul Ariff Othman is an adjunct lecturer at Universiti Teknologi Petronas, international relations analyst and a senior consultant with Global Asia Consulting. The views in this OpEd piece are entirely his own.

MalaySIAL will be Economically, financially, socially CURSED because it CURSE Isreal..... Nothing good come from Hamas Lover Anwar PMX and its Allies in DAP - the Dhimmi, Delusion, deceiving .... AUTA Party...wa ka ka. Lets Hope when Oil Drops below USD$60 a barrel, Malaysia in DEEP DEFICIT SH*T Come GE16 like $2.3 Trillion....INFLATION Hamas Lover Anwar Finance Minister Barang TERUK Naik Unity SH*T Government gets Kicked out and PAS Takes Power....Sh*t Hole Nation Double down in the making.... MALAYSIAL WILL GET THE WORST OF WORST AS LONG AS THE FACIST SUPREMACIST HAMAS BROTHERHOOD OF ISLAM CONTINUE THEIR FAKE FRAUD DEVELOPMENT SH*T....WHEN YOU DEVELOP SH*T Economy.... You Get SH*T Outcome...simple economy VALUE ADDING for A CURSED NATION...... Don't bother comparing to Singapore....... Beter start comparing to Bangladesh, Pakistan, Turkey, Yemen, Afganistan, Myanmar.....those SH*T hole Nation... The challenge is for HAMAS HATERS IN MALAYSIA to INVEST/PROFIT WITHOUT LETTING THE HAMAS LOVER KNOW YOUR SECRET!!

ReplyDelete