Murray Hunter

18 Feb 2025, 15:57 (9 hours ago)

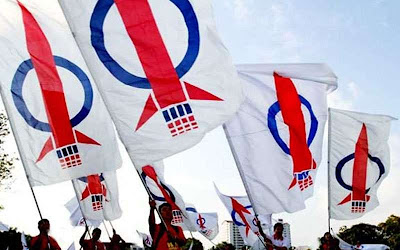

Factionalism and power struggles within the DAP: A generational and ideological divide

P Ramasamy

Some veteran DAP leaders are raising concerns about the existence of a “deep state” operating within the party, allegedly led by younger party members aiming to unseat key senior leaders.

Comparisons have been drawn to the 1990s “Kick Out Kit Siang” (KOKS) campaign that sought to remove Lim Kit Siang, one of the party’s most prominent figures.

While current discussions of a “deep state” center around efforts to unseat senior leaders, no attention is being paid to how senior leaders themselves have marginalized younger and competent leaders in the past.

The survival of many senior leaders has often depended on a series of political purges over the years.

For instance, in the last general election, a senior Indian leader was purged from contesting a parliamentary seat, replaced by a compliant candidate.

Similarly, prior to the 2003 state elections, several outspoken Indian leaders were removed from contention.

Could these past actions be considered the work of the “deep state”?

If senior leaders were responsible for these purges, were they themselves part of this so-called phenomenon?

This raises an important question: Is the concept of a “deep state” being arbitrarily invoked to describe opposition to senior leaders?

Historically, no one used such terminology when senior leaders marginalized others.

The DAP, like other political parties in the country, is no stranger to generational conflicts and power struggles.

Is it acceptable for senior leaders to have employed undemocratic measures to sideline opponents in the past?

Opposition to family-based factions within the party has simmered for years but is now a more prominent source of internal conflict.

Nepotism and cronyism among senior party leaders cannot be defended, and these grievances may be fueling frustrations among the younger generations of leaders.

The current factional conflicts may also be influenced by differing attitudes toward Malay hegemony.

Senior leaders are often seen as more aggressive on such issues, while some younger leaders appear more willing to adapt to Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s style of politics.

There are also accusations that younger leaders have abandoned the DAP’s long-standing vision of a “Malaysian Malaysia.”

As party elections approach in March, these simmering tensions have escalated into a “do or die” struggle between generations.

Whether the conflict is ideological or generational, one thing is clear: the DAP today is not the party it once was.

Many now argue that the DAP, once an aggressive champion for non-Malay rights, has begun to resemble the MCA—a Chinese-majority party with token representation from Malays and Indians for the sake of multiracial optics.

As these internal conflicts continue, the future direction of the DAP remains uncertain.

Some veteran DAP leaders are raising concerns about the existence of a “deep state” operating within the party, allegedly led by younger party members aiming to unseat key senior leaders.

Comparisons have been drawn to the 1990s “Kick Out Kit Siang” (KOKS) campaign that sought to remove Lim Kit Siang, one of the party’s most prominent figures.

While current discussions of a “deep state” center around efforts to unseat senior leaders, no attention is being paid to how senior leaders themselves have marginalized younger and competent leaders in the past.

The survival of many senior leaders has often depended on a series of political purges over the years.

For instance, in the last general election, a senior Indian leader was purged from contesting a parliamentary seat, replaced by a compliant candidate.

Similarly, prior to the 2003 state elections, several outspoken Indian leaders were removed from contention.

Could these past actions be considered the work of the “deep state”?

If senior leaders were responsible for these purges, were they themselves part of this so-called phenomenon?

This raises an important question: Is the concept of a “deep state” being arbitrarily invoked to describe opposition to senior leaders?

Historically, no one used such terminology when senior leaders marginalized others.

The DAP, like other political parties in the country, is no stranger to generational conflicts and power struggles.

Is it acceptable for senior leaders to have employed undemocratic measures to sideline opponents in the past?

Opposition to family-based factions within the party has simmered for years but is now a more prominent source of internal conflict.

Nepotism and cronyism among senior party leaders cannot be defended, and these grievances may be fueling frustrations among the younger generations of leaders.

The current factional conflicts may also be influenced by differing attitudes toward Malay hegemony.

Senior leaders are often seen as more aggressive on such issues, while some younger leaders appear more willing to adapt to Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s style of politics.

There are also accusations that younger leaders have abandoned the DAP’s long-standing vision of a “Malaysian Malaysia.”

As party elections approach in March, these simmering tensions have escalated into a “do or die” struggle between generations.

Whether the conflict is ideological or generational, one thing is clear: the DAP today is not the party it once was.

Many now argue that the DAP, once an aggressive champion for non-Malay rights, has begun to resemble the MCA—a Chinese-majority party with token representation from Malays and Indians for the sake of multiracial optics.

As these internal conflicts continue, the future direction of the DAP remains uncertain.

P. Ramasamy

Former professor of political economy at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) and former deputy chief minister of Penang.

No comments:

Post a Comment