Asean nations caught in a quandary

By M. VEERA PANDIYAN

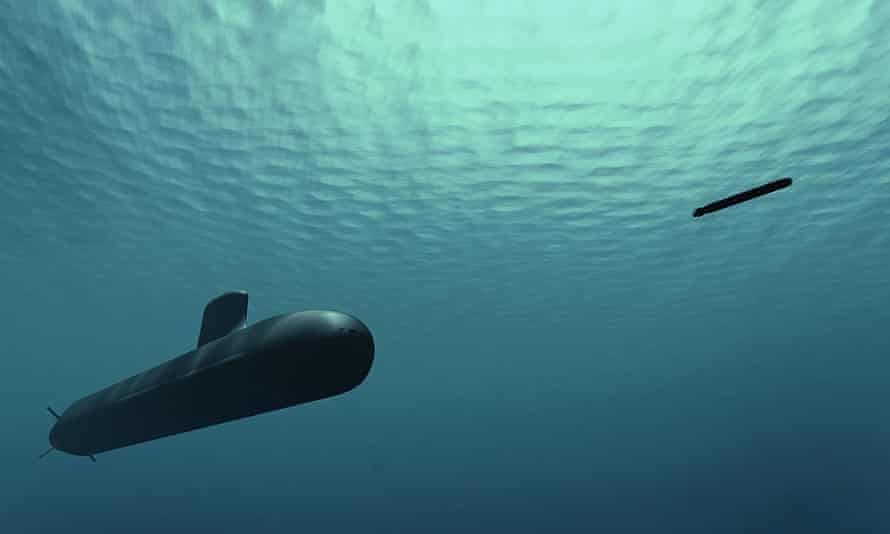

The agreement, under which the US and the UK would provide Australia the technology to build nuclear-powered submarines for the first time, was declared in a joint virtual press conference by US President Joe Biden, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Australian PM Scott Morrison on Sept 15.The three Anglo Saxon nations declared that the new deal is meant to protect and defend shared interests in the Indo-Pacific amid “regional security concerns which had grown significantly”.

The epithet “deputy sheriff of the US” first gained infamy 22 years ago when then Australian PM John Howard used it in an interview to describe the country’s projected role in regional peacekeeping.

He also said Australia had a responsibility within its region to do things “above and beyond”, bringing into play its unique characteristics as a Western country in Asia.

The remarks led to both ridicule at home and diplomatic backlash from regional leaders who rebuked Australia for taking orders from the United States while being geographically closer to Asia. History repeats itself often, and Australia’s partnership in Aukus has brought the focus back on that lackey image.

Based on the reactions over the past few days, two camps have emerged. Malaysia and Indonesia are clearly opposed to it on the grounds that it would unsettle the region. Thailand, a traditional US ally which has a close economic relationship with China, is also of the view that the security pact would undermine stability.

On the opposite side, the Philippines has taken a totally contrary stand. It has declared support, with its foreign minister Teodoro Locsin arguing that Aukus would address the imbalance in the forces available to the Asean member states and that the enhancement of Australia’s military capacity would be beneficial in the long term.

Vietnam, which recently hosted US vice-president Kamala Harris, has not commented on the pact although its spokesperson Le Thi Thu Hang offered this ambiguous response: “All countries strive for the same goal.”

Meanwhile, Singapore Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan has stated that the city state is “not unduly anxious” about the new strategic alliance because of its longstanding relationship with the three countries.

The four other countries in the grouping have been largely silent on the issue.

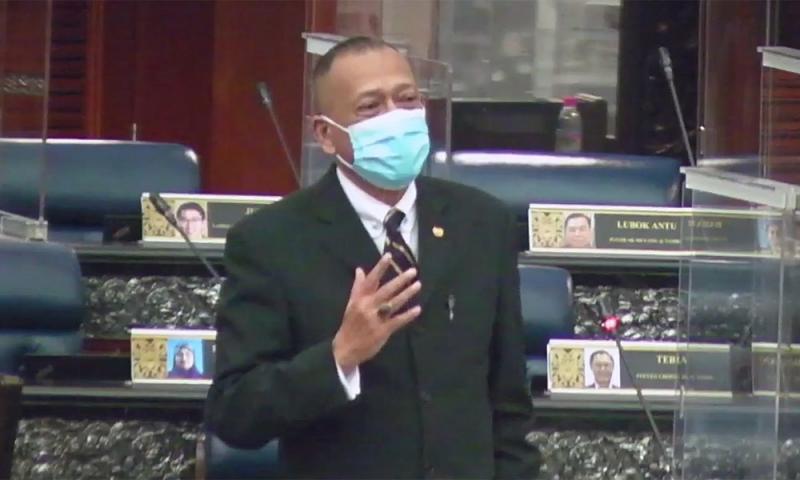

Malaysia was swift and forthright in making its position clear. Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob warned that Aukus would spark a nuclear arms race and provoke other powers to act more aggressively in the region, especially in the South China Sea.

In his phone call to Morrison, he also raised the importance of abiding by existing positions on nuclear-powered submarines operating in Malaysia’s waters, including rules under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (UNCLOS) and the Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty (SEANWFZ).

The questions being asked now are: How will China react to Aukus? Will it intensify the arms technology race in the region by increasing military expenditure for its navy or create more missile launch facilities, also known as underground missile silos, for the storage and launching of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs)?

That is what is being predicted by the hawks in the US military establishment, who have been consistently exaggerating China’s supposed military threat.

Among the talk is that China would boost the number of missile silos to 100 over the next two decades. For the record, the US already has at least 450 such facilities.

It is no secret that China has been building up its navy although it is still a long way from matching the marine power of the United States or the United Kingdom with just two aircraft carriers and a third still under construction. In comparison, the United States has 11 aircraft carriers and the United Kingdom two, but only one has been commissioned.

The US has 72 submarines – all nuclear-powered – compared with China’s 56, out of which only six are nuclear-powered.

With the entry of this newfangled military pact, Asean nations are now caught in a quandary. The quest for a Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality in South-East Asia (Zopfan) declared on Nov 27, 1971, when the world was in the midst of a Cold War between the US and its Western allies and the USSR, looks like a distant dream today.

Zopfan was mainly aimed at preventing the world’s big powers from competing for influence and military prowess in the region.

The concept was inspired by the UN’s principles of respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states, abstention from threat or use of force, peaceful settlement of international disputes, equal rights and self-determination, and non-interference in the affairs of member states.

But as Dr Laura Southgate, a specialist in South-East Asian regional security and international relations, highlighted in a recent article in The Diplomat, Aukus has clearly exposed Asean’s lack of cohesion.

As she put it, driven by different threat perceptions and geo-strategic interests, it had become very difficult for Asean member nations to speak with one voice, although many states hope to maintain a balance between China and the US and its allies.

Media consultant M. Veera Pandiyan likes this observation by Niccolò Machiavelli: “Wars begin when you will, but they do not end when you please.” The views expressed here are the writer’s own