Murray Hunter

The Chola incursion into Southeast Asia: Maritime rivalry, not imperialism

P Ramasamy

Apr 25, 2025

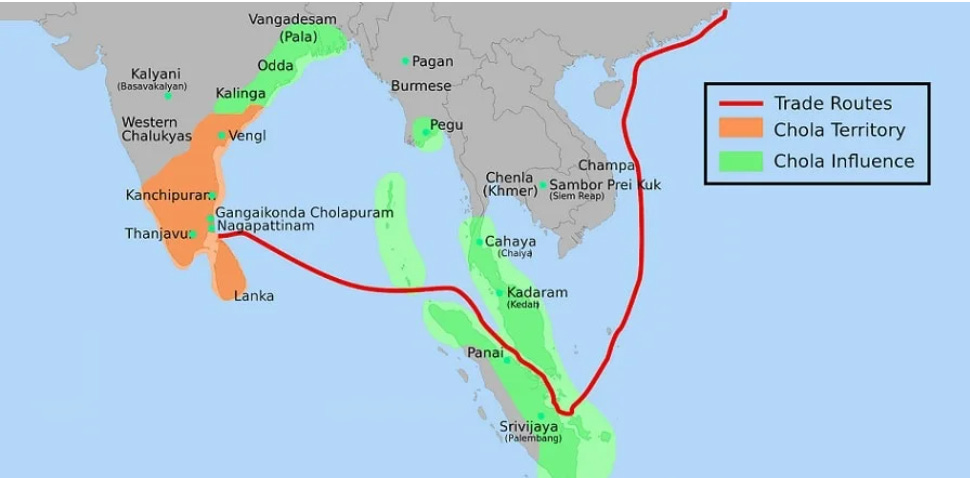

The Chola Empire, based in South India, represents one of the most remarkable maritime powers in early medieval Asia.

At the height of their influence in the 11th century, the Cholas extended their reach beyond the Indian subcontinent, projecting their naval might deep into Southeast Asia.

Their most notable intervention came in the form of a military expedition against the Srivijayan Kingdom, which dominated the maritime trade routes of the region.

Contrary to the pattern of later European colonial powers, the Chola expansion was not driven by an imperial ambition to control overseas territories. While their campaigns extended far beyond their immediate borders, including incursions into present-day Sri Lanka and parts of Southeast Asia, the underlying motivations were largely economic and strategic rather than territorial.

The 11th-century expedition to the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, particularly the invasion of Kedaram (present-day Kedah), was precipitated by rising maritime tensions.

The Cholas, who were active players in the booming Indian Ocean trade, found themselves disadvantaged by the heavy maritime taxes imposed by the Srivijayan Kingdom—a powerful thalassocracy centered in Sumatra that controlled key maritime chokepoints, particularly the Straits of Malacca.

At the time, Srivijaya enjoyed “most favoured nation” status with the Chinese empire, a status that enabled it to dominate trade in the region. The Cholas, likely perceiving both economic marginalization and strategic encirclement, responded with a decisive naval assault. Rajendra Chola I launched an expedition around 1025 CE that targeted Srivijayan settlements along the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, including Kedaram. The campaign was swift and brutal, effectively crippling Srivijaya’s regional authority.

Importantly, the Chola intervention did not result in a long-term colonial presence. While Chola influence lingered in the region for about 66 years, they eventually restored Kedaram to a Srivijayan prince, signaling a lack of imperial intent. Their primary objective had been to assert maritime dominance and secure favorable trade conditions, not to rule distant territories.

My personal engagement with this subject stems from my two-year academic affiliation with the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), Singapore, during which I organized a major international conference titled Early Indian Influence in Southeast Asia, with a particular focus on the Chola maritime expeditions.

The conference brought together renowned scholars and experts in the field to shed light on this fascinating period of intercultural contact and maritime rivalry.

Following the conference, I embarked on a research expedition to the Merbok Valley in Kedah alongside an Indian naval officer. Our mission was to explore potential Chola landing sites and assess the navigational significance of the nine Hindu temples on Gunung Jerai. We speculated that these temples could have served as maritime beacons guiding Chola ships into the Merbok River. Our research also took us to the Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum, where we searched for tangible evidence of the Chola presence in the region.

The results of our scholarly and field efforts culminated in the publication of two edited volumes by ISEAS—one on early Indian influence in Southeast Asia, and another specifically on the Chola voyages.

In retrospect, the Chola intervention in Southeast Asia should be understood not through the lens of imperial conquest, but as a calculated assertion of maritime rights in a competitive and vibrant trade environment. The campaign against Srivijaya was a strategic maneuver rooted in economic rivalry, not a prelude to colonization.

Apr 25, 2025

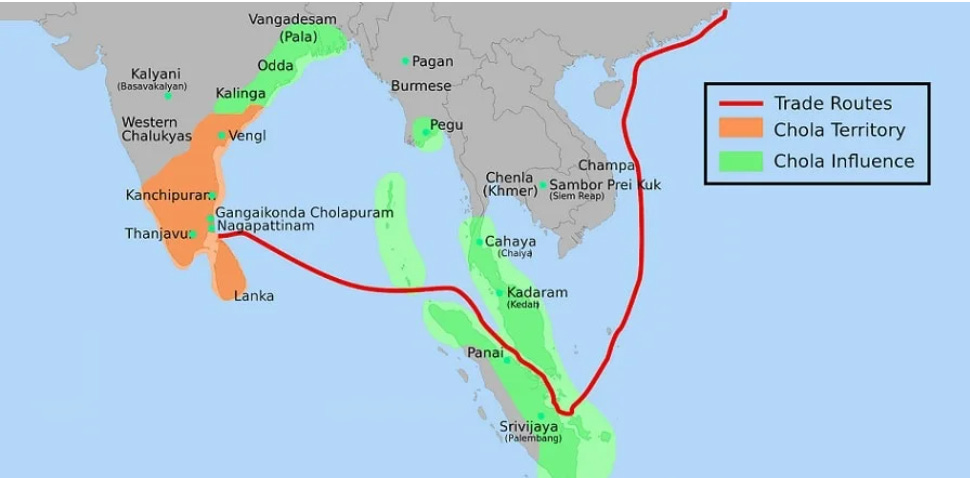

The Chola Empire, based in South India, represents one of the most remarkable maritime powers in early medieval Asia.

At the height of their influence in the 11th century, the Cholas extended their reach beyond the Indian subcontinent, projecting their naval might deep into Southeast Asia.

Their most notable intervention came in the form of a military expedition against the Srivijayan Kingdom, which dominated the maritime trade routes of the region.

Contrary to the pattern of later European colonial powers, the Chola expansion was not driven by an imperial ambition to control overseas territories. While their campaigns extended far beyond their immediate borders, including incursions into present-day Sri Lanka and parts of Southeast Asia, the underlying motivations were largely economic and strategic rather than territorial.

The 11th-century expedition to the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, particularly the invasion of Kedaram (present-day Kedah), was precipitated by rising maritime tensions.

The Cholas, who were active players in the booming Indian Ocean trade, found themselves disadvantaged by the heavy maritime taxes imposed by the Srivijayan Kingdom—a powerful thalassocracy centered in Sumatra that controlled key maritime chokepoints, particularly the Straits of Malacca.

At the time, Srivijaya enjoyed “most favoured nation” status with the Chinese empire, a status that enabled it to dominate trade in the region. The Cholas, likely perceiving both economic marginalization and strategic encirclement, responded with a decisive naval assault. Rajendra Chola I launched an expedition around 1025 CE that targeted Srivijayan settlements along the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, including Kedaram. The campaign was swift and brutal, effectively crippling Srivijaya’s regional authority.

Importantly, the Chola intervention did not result in a long-term colonial presence. While Chola influence lingered in the region for about 66 years, they eventually restored Kedaram to a Srivijayan prince, signaling a lack of imperial intent. Their primary objective had been to assert maritime dominance and secure favorable trade conditions, not to rule distant territories.

My personal engagement with this subject stems from my two-year academic affiliation with the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), Singapore, during which I organized a major international conference titled Early Indian Influence in Southeast Asia, with a particular focus on the Chola maritime expeditions.

The conference brought together renowned scholars and experts in the field to shed light on this fascinating period of intercultural contact and maritime rivalry.

Following the conference, I embarked on a research expedition to the Merbok Valley in Kedah alongside an Indian naval officer. Our mission was to explore potential Chola landing sites and assess the navigational significance of the nine Hindu temples on Gunung Jerai. We speculated that these temples could have served as maritime beacons guiding Chola ships into the Merbok River. Our research also took us to the Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum, where we searched for tangible evidence of the Chola presence in the region.

The results of our scholarly and field efforts culminated in the publication of two edited volumes by ISEAS—one on early Indian influence in Southeast Asia, and another specifically on the Chola voyages.

In retrospect, the Chola intervention in Southeast Asia should be understood not through the lens of imperial conquest, but as a calculated assertion of maritime rights in a competitive and vibrant trade environment. The campaign against Srivijaya was a strategic maneuver rooted in economic rivalry, not a prelude to colonization.

P. Ramasamy, Chairman, Urimai

No comments:

Post a Comment