Bridget Welsh

Published: Nov 23, 2024 3:35 PM

COMMENT | Today marks the two-year anniversary of the Anwar Ibrahim Madani government. His supporters will laud his achievements in securing political stability, economic growth, and foreign investment, while his critics will point to the lack of democratic reforms and embrace of conservative Islamisation.

These issues have been covered in-depth in assessments, including in my earlier columns and the recent Bersih report card on reforms.

This piece highlights four other aspects of the Madani government that have taken root in the last year.

Modest Madani electoral swing

Among the public, the prime minister’s support remains polarised across different communities in Malaysia. Despite the Madani government winning three of the four by-elections this year (all at the state level), and securing a change in electoral fortunes in Nenggiri, the gaps in public support persist, especially among Malay and younger voters.

If there has been any movement in voting over the last year, it has been to Umno rather than any of the other component parties in the government. Umno’s gains are also more modest than might be assumed as they have come at the expense of Bersatu rather than PAS, yet the party has gained from being in government as it did for a short period after the 2020 Sheraton Move.

Published: Nov 23, 2024 3:35 PM

COMMENT | Today marks the two-year anniversary of the Anwar Ibrahim Madani government. His supporters will laud his achievements in securing political stability, economic growth, and foreign investment, while his critics will point to the lack of democratic reforms and embrace of conservative Islamisation.

These issues have been covered in-depth in assessments, including in my earlier columns and the recent Bersih report card on reforms.

This piece highlights four other aspects of the Madani government that have taken root in the last year.

Modest Madani electoral swing

Among the public, the prime minister’s support remains polarised across different communities in Malaysia. Despite the Madani government winning three of the four by-elections this year (all at the state level), and securing a change in electoral fortunes in Nenggiri, the gaps in public support persist, especially among Malay and younger voters.

If there has been any movement in voting over the last year, it has been to Umno rather than any of the other component parties in the government. Umno’s gains are also more modest than might be assumed as they have come at the expense of Bersatu rather than PAS, yet the party has gained from being in government as it did for a short period after the 2020 Sheraton Move.

BN winning the Nenggiri by-election in Kelantan on Aug 17

For Pakatan Harapan, its second year in office has increased the coalition’s electoral vulnerability as more non-Malays and wealthier voters become disenchanted with being taken for granted and choosing not to vote.

Tethered alliances

In year two at the helm, Anwar has moved away from a “save-the-government” focus on the political survival of the elites and is engaging in governance. Now two budgets, hundreds of speeches, multiple blueprints and plans later, it is clear that attention has moved more outward than inward.

Yet the relationships between Anwar and different parties have changed. Umno remains the dominant party in the Madani government, with appeasement of the demands of its leaders evident. Umno has been allowed to be Umno through patronage and ethnicised rhetoric.

Relations with Borneo on the surface have appeared cordial, with increased funds for both Sabah and Sarawak, but year two has seen an intensification of demands and pressures, laden with quiet dissatisfaction. Resentments simmer under the surface, with a noticeable backlash in Peninsular Malaysia to the rising demands from Borneo. Sarawak’s GPS remains a dominant player in national politics and uses its political clout well to position itself for greater autonomy.

While DAP contributes the most seats to the government, it has been more silent over the last year, at least compared to its past. DAP no longer has the same opposition orientation and is wrestling with tensions between principles and power. As with the Madani government’s response to non-Malay voters, the DAP appears less valued in the government compared to the other two big guns - UMNO and GPS; its political support for Anwar is similarly taken for granted.

For Pakatan Harapan, its second year in office has increased the coalition’s electoral vulnerability as more non-Malays and wealthier voters become disenchanted with being taken for granted and choosing not to vote.

Tethered alliances

In year two at the helm, Anwar has moved away from a “save-the-government” focus on the political survival of the elites and is engaging in governance. Now two budgets, hundreds of speeches, multiple blueprints and plans later, it is clear that attention has moved more outward than inward.

Yet the relationships between Anwar and different parties have changed. Umno remains the dominant party in the Madani government, with appeasement of the demands of its leaders evident. Umno has been allowed to be Umno through patronage and ethnicised rhetoric.

Relations with Borneo on the surface have appeared cordial, with increased funds for both Sabah and Sarawak, but year two has seen an intensification of demands and pressures, laden with quiet dissatisfaction. Resentments simmer under the surface, with a noticeable backlash in Peninsular Malaysia to the rising demands from Borneo. Sarawak’s GPS remains a dominant player in national politics and uses its political clout well to position itself for greater autonomy.

While DAP contributes the most seats to the government, it has been more silent over the last year, at least compared to its past. DAP no longer has the same opposition orientation and is wrestling with tensions between principles and power. As with the Madani government’s response to non-Malay voters, the DAP appears less valued in the government compared to the other two big guns - UMNO and GPS; its political support for Anwar is similarly taken for granted.

DAP supporters

These three dynamics - appeasement, accommodation, and acquiescence - reflect the respective evolving relationships among core members of the Madani government. They speak to Anwar’s strong capacity to manage relationships among the elites. At the same time, they showcase the persistent vulnerability of Anwar politically, as he is tethered to political alliances.

Despite co-existence, the inward issues of the Madani government remain salient. It is clear, however, that drivers to stay put in the Madani government are dominant - at least for now.

Forging of a political Madani cartel

In fact, year two has seen a modest strengthening of cooperation among the different Madani parties, at least among older and appointed-to-government elites. The grassroots are far from this, notably youth divisions.

Yet the idea of the “Madani cartel” is taking shape, where electoral cooperation is seen as needed to limit the opposition’s gains. Anwar’s idea of a unity, broad coalition, is being reinforced, with proponents pushing openly for more consolidation to maintain access to power and its spoils.

Inevitably, two years of working together will increase familiarity. Rather than breeding contempt, it has bred greater acceptance among parties in government. In fact, it has arguably encouraged ambitions, with the cartel seen by some as the means to a second term.

Personalised power

The man holding the political cartel together is the prime minister. Year two has also showcased his dominance in the government. Gone is the idea of equality among partners, as governance has been centred on Anwar’s leadership.

These three dynamics - appeasement, accommodation, and acquiescence - reflect the respective evolving relationships among core members of the Madani government. They speak to Anwar’s strong capacity to manage relationships among the elites. At the same time, they showcase the persistent vulnerability of Anwar politically, as he is tethered to political alliances.

Despite co-existence, the inward issues of the Madani government remain salient. It is clear, however, that drivers to stay put in the Madani government are dominant - at least for now.

Forging of a political Madani cartel

In fact, year two has seen a modest strengthening of cooperation among the different Madani parties, at least among older and appointed-to-government elites. The grassroots are far from this, notably youth divisions.

Yet the idea of the “Madani cartel” is taking shape, where electoral cooperation is seen as needed to limit the opposition’s gains. Anwar’s idea of a unity, broad coalition, is being reinforced, with proponents pushing openly for more consolidation to maintain access to power and its spoils.

Inevitably, two years of working together will increase familiarity. Rather than breeding contempt, it has bred greater acceptance among parties in government. In fact, it has arguably encouraged ambitions, with the cartel seen by some as the means to a second term.

Personalised power

The man holding the political cartel together is the prime minister. Year two has also showcased his dominance in the government. Gone is the idea of equality among partners, as governance has been centred on Anwar’s leadership.

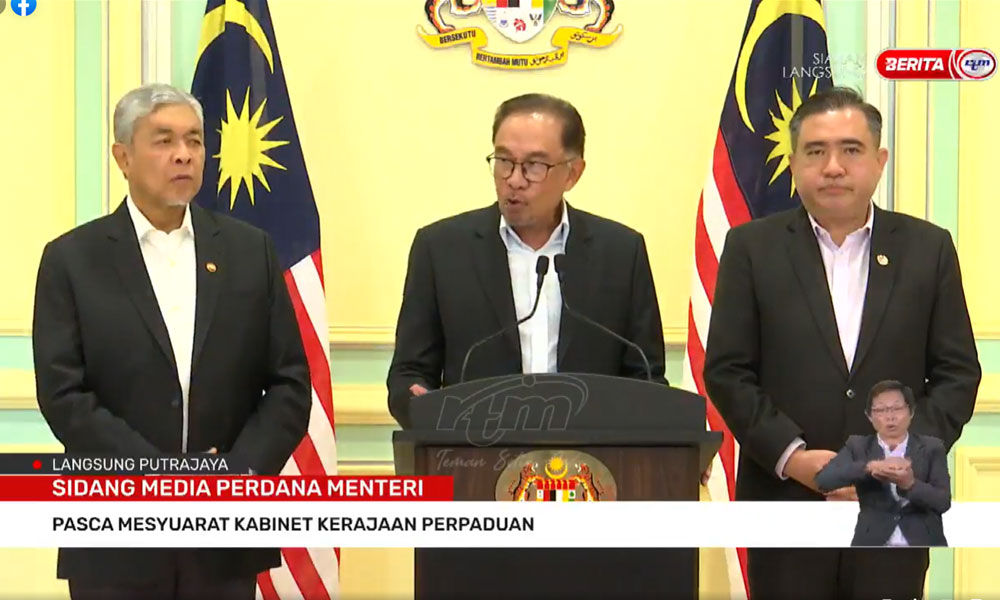

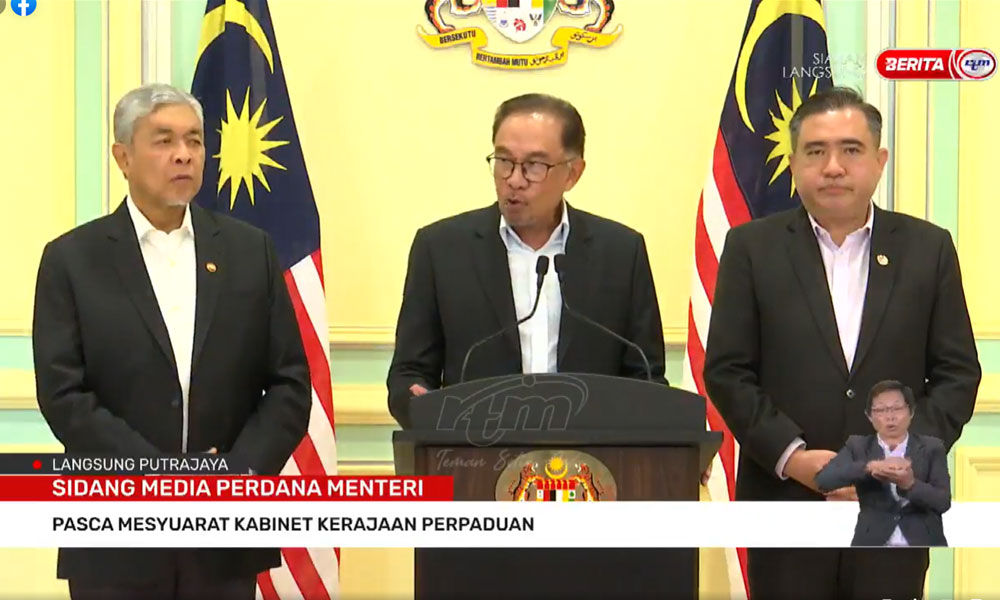

(L-R) Deputy Prime Minister and Umno chief Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, Prime Minister and Pakatan Harapan chairperson Anwar Ibrahim, and DAP secretary-general Anthony Loke

This too is inevitable given the leader-centred focus of Malaysian politics, centralised decision-making in political institutions, and feudal political culture.

Yet, under Madani, this is a different configuration - one where the prime minister is weaker, without his own electoral mandate to be prime minister, while simultaneously working to appear stronger. Over the past year, the government’s public projection has been overwhelmingly about Anwar. Other ministers get mentioned but rarely overshadow the Madani star.

Year two of the Madani government has seen a return to greater personalisation of power around the prime minister. This has not been the case to the same extent since Mahathir left office in 2004 - the branding, the regular public commentary on a wide range of issues, and the projection of the nation’s future around one man.

The effects of this are likely to evolve as Anwar’s tenure at the helm continues. In the past, it led to even more centralisation of power, less acceptance of alternative views, and limited space for younger leaders to strengthen their own political base.

The burden on Anwar to perform has gained more traction, as he - and he alone - is tied to electoral performance, alliance ties, and the future of the Madani political cartel. Personalisation of power brings both rewards and risks.

This is a hard burden to bear at a time of global uncertainty and greater demands from citizens for better governance. It will make year three even more challenging.

This too is inevitable given the leader-centred focus of Malaysian politics, centralised decision-making in political institutions, and feudal political culture.

Yet, under Madani, this is a different configuration - one where the prime minister is weaker, without his own electoral mandate to be prime minister, while simultaneously working to appear stronger. Over the past year, the government’s public projection has been overwhelmingly about Anwar. Other ministers get mentioned but rarely overshadow the Madani star.

Year two of the Madani government has seen a return to greater personalisation of power around the prime minister. This has not been the case to the same extent since Mahathir left office in 2004 - the branding, the regular public commentary on a wide range of issues, and the projection of the nation’s future around one man.

The effects of this are likely to evolve as Anwar’s tenure at the helm continues. In the past, it led to even more centralisation of power, less acceptance of alternative views, and limited space for younger leaders to strengthen their own political base.

The burden on Anwar to perform has gained more traction, as he - and he alone - is tied to electoral performance, alliance ties, and the future of the Madani political cartel. Personalisation of power brings both rewards and risks.

This is a hard burden to bear at a time of global uncertainty and greater demands from citizens for better governance. It will make year three even more challenging.

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute, a senior research associate at Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com

A former colleague from India was in the run. He shared a picture of the run together with his wife and children. Happy for him.

ReplyDelete~~~~~

https://x.com/HSajwanization/status/1860568743249658039?s=19

Today morning, Dubai and the arab world’s busiest and the most important road, Sheikh Zayed Road E11 turned into the world’s biggest running track.

Dubai Run 🏃🏻 🇦🇪