Dr M unable to stop probe into BMF scandal

Kee Thuan Chye

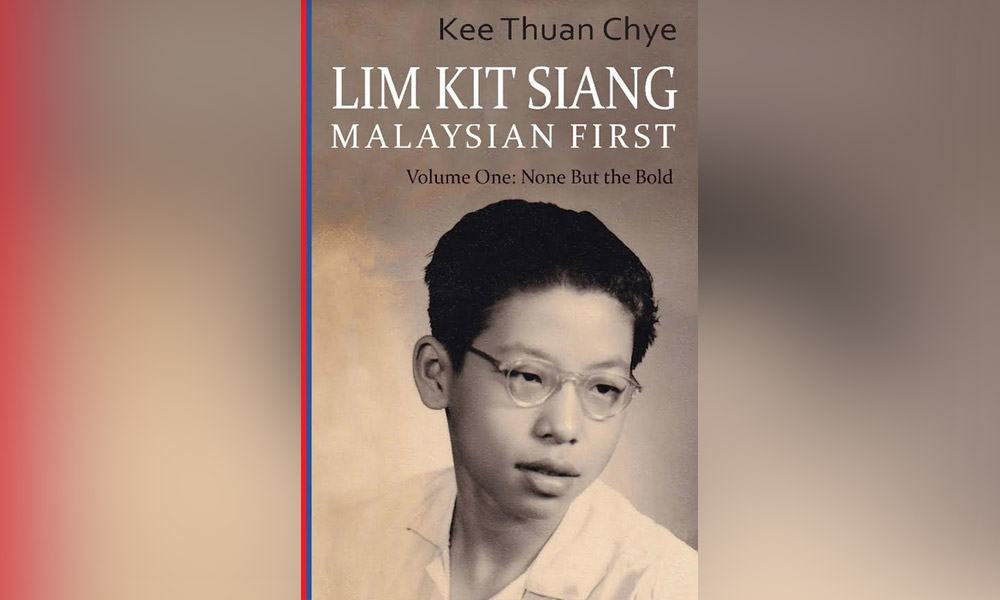

The following is an exclusive excerpt from Chapter 30 of ‘Lim Kit Siang: Malaysian First, Volume One: None But the Bold’, a new biography by Kee Thuan Chye.

In January 1984, Dr Mahathir Mohamad finally conceded to public pressure and set up a three-man committee of inquiry into the BMF scandal. It was, however, not the royal commission of inquiry that Lim Kit Siang had repeatedly asked for.

The committee would be headed by the government’s auditor-general, Ahmad Noordin Zakaria, described by Kit as a man “famous for his impeccable integrity”, and assisted by lawyer Chooi Mun Sou and accountant Ramli Ibrahim. Mahathir told the media that they had been selected “on the basis of their neutral standing in the affair”.

All the same, few Malaysians expected the committee to get far in its investigations given the complexity of the case, the political pitfalls that it would probably face, and the narrowness of its terms of reference since it was briefed to probe only the Carrian link with BMF, excluding the bank’s relationships with Kevin Hsu and the Eda Group.

Kit expressed his party’s disappointment with the arrangement. He said “nobody believes that a handful of BMF officials” could commit loans to the tune of RM2.5 billion “without the highest political approval being granted”, and therefore only a high-powered inquiry like an RCI could get to the bottom of the scandal.

The following is an exclusive excerpt from Chapter 30 of ‘Lim Kit Siang: Malaysian First, Volume One: None But the Bold’, a new biography by Kee Thuan Chye.

In January 1984, Dr Mahathir Mohamad finally conceded to public pressure and set up a three-man committee of inquiry into the BMF scandal. It was, however, not the royal commission of inquiry that Lim Kit Siang had repeatedly asked for.

The committee would be headed by the government’s auditor-general, Ahmad Noordin Zakaria, described by Kit as a man “famous for his impeccable integrity”, and assisted by lawyer Chooi Mun Sou and accountant Ramli Ibrahim. Mahathir told the media that they had been selected “on the basis of their neutral standing in the affair”.

All the same, few Malaysians expected the committee to get far in its investigations given the complexity of the case, the political pitfalls that it would probably face, and the narrowness of its terms of reference since it was briefed to probe only the Carrian link with BMF, excluding the bank’s relationships with Kevin Hsu and the Eda Group.

Kit expressed his party’s disappointment with the arrangement. He said “nobody believes that a handful of BMF officials” could commit loans to the tune of RM2.5 billion “without the highest political approval being granted”, and therefore only a high-powered inquiry like an RCI could get to the bottom of the scandal.

... time before KHAT took the road to Thiruvananthapuram

In September, Ahmad Noordin himself supported the RCI proposal. He told the national news agency Bernama that only an RCI, headed by a judge, would have the power to establish if anyone was criminally liable as it could summon witnesses to testify under oath.

By then, Ahmad Noordin and his committee had already submitted their first interim report to Bank Bumiputera on Aug 17, after seven months of hard work. But the government was reluctant to release it.

The public was therefore moved to intensify its pressure on the government to do the right thing. The DAP, too, was unrelenting in its provocation.

In response, Mahathir accused those who demanded an open inquiry into the scandal of wanting to topple the Malay leaders and destroy Bank Bumiputera, thus turning it into a racial issue when it clearly wasn’t one.

To this, Kit astutely and rightly replied, “If there is anyone who is trying to oust the Malay political leadership and destroy Bank Bumiputera, it is those who are responsible for the ‘heinous crime’ of the BMF loans scandal.”

He also complained that after two months of receiving the report, the cabinet had yet to study it because Mahathir said it hadn’t had the time to do so. “I find this most shocking,” Kit said. “What then has the cabinet time for?”

Meanwhile, former prime minister Hussein Onn joined the fray by echoing the call for an RCI to investigate the scandal and also for the inquiry committee’s report to be published. This could have given a boost to the public pressure, because on Jan 2, 1985, the interim report was finally released.

‘Appalled and disturbed’

On Jan 8, Reuters reported positively on the committee’s work. It said the committee had “surprised its critics by the doggedness” with which it had pursued the investigation. Not only did it establish the extent of the bad loans committed by BMF, it also exposed six BMF executives and their relatives for having received payments from George Tan and his Carrian Group.

They were the three original BMF board members – Lorrain [Esme Osman], Hashim [Shamsuddin] and Rais [Saniman] – and three former senior BMF officials – Ibrahim [Jaafar], Henry Chin and Eric Chow. And they were liable to be charged with corruption.

The committee also found that BMF continued to lend to Carrian after the group had announced in October 1982 that it could not pay its debts. This was a new and stunning revelation.

Reuters wrote that this continued lending in 1983 had “embarrassed” Bank Bumiputera’s former executive chairman, Nawawi Mat Awin, who had resigned a week earlier. It had also embarrassed “the man who appointed him in 1982, Prime Minister Mahathir”.

The report was well-received by the public. Hussein Onn was appalled and disturbed by what it divulged. He commented that the scandal was “the worst blow in the history of Malay management, especially in banking and finance”.

By then, Ahmad Noordin and his committee had already submitted their first interim report to Bank Bumiputera on Aug 17, after seven months of hard work. But the government was reluctant to release it.

The public was therefore moved to intensify its pressure on the government to do the right thing. The DAP, too, was unrelenting in its provocation.

In response, Mahathir accused those who demanded an open inquiry into the scandal of wanting to topple the Malay leaders and destroy Bank Bumiputera, thus turning it into a racial issue when it clearly wasn’t one.

To this, Kit astutely and rightly replied, “If there is anyone who is trying to oust the Malay political leadership and destroy Bank Bumiputera, it is those who are responsible for the ‘heinous crime’ of the BMF loans scandal.”

He also complained that after two months of receiving the report, the cabinet had yet to study it because Mahathir said it hadn’t had the time to do so. “I find this most shocking,” Kit said. “What then has the cabinet time for?”

Meanwhile, former prime minister Hussein Onn joined the fray by echoing the call for an RCI to investigate the scandal and also for the inquiry committee’s report to be published. This could have given a boost to the public pressure, because on Jan 2, 1985, the interim report was finally released.

‘Appalled and disturbed’

On Jan 8, Reuters reported positively on the committee’s work. It said the committee had “surprised its critics by the doggedness” with which it had pursued the investigation. Not only did it establish the extent of the bad loans committed by BMF, it also exposed six BMF executives and their relatives for having received payments from George Tan and his Carrian Group.

They were the three original BMF board members – Lorrain [Esme Osman], Hashim [Shamsuddin] and Rais [Saniman] – and three former senior BMF officials – Ibrahim [Jaafar], Henry Chin and Eric Chow. And they were liable to be charged with corruption.

The committee also found that BMF continued to lend to Carrian after the group had announced in October 1982 that it could not pay its debts. This was a new and stunning revelation.

Reuters wrote that this continued lending in 1983 had “embarrassed” Bank Bumiputera’s former executive chairman, Nawawi Mat Awin, who had resigned a week earlier. It had also embarrassed “the man who appointed him in 1982, Prime Minister Mahathir”.

The report was well-received by the public. Hussein Onn was appalled and disturbed by what it divulged. He commented that the scandal was “the worst blow in the history of Malay management, especially in banking and finance”.

Former prime minister Hussein Onn

“We had been growing and learning, but now we have gone back I don’t know how many years. This is the sad part,” he said. “I offer no apology. As a Malay, I cannot take it. It is a slap to us. The Malays must be critical and ask how it happened. The people have a right to know what is the real story.”

Ahmad Noordin, Mun Sou and Ramli were celebrated as folk heroes. In February, The Star paid tribute to them by naming the committee ‘Malaysian of the Year 1984’. In its citation, the newspaper said the committee had done its job despite “endless obstacles”. The newspaper lauded them for having “named names and called a spade a spade”.

Hussein Onn continued to add pressure by urging the government not to drag its feet and to take the necessary legislative action to enable the culprits to be prosecuted in the country.

But in July, the attorney-general, Abu Talib Othman, dropped a bombshell. He said the government had no jurisdiction to try the former BMF officials because the offences were committed outside the country.

“We had been growing and learning, but now we have gone back I don’t know how many years. This is the sad part,” he said. “I offer no apology. As a Malay, I cannot take it. It is a slap to us. The Malays must be critical and ask how it happened. The people have a right to know what is the real story.”

Ahmad Noordin, Mun Sou and Ramli were celebrated as folk heroes. In February, The Star paid tribute to them by naming the committee ‘Malaysian of the Year 1984’. In its citation, the newspaper said the committee had done its job despite “endless obstacles”. The newspaper lauded them for having “named names and called a spade a spade”.

Hussein Onn continued to add pressure by urging the government not to drag its feet and to take the necessary legislative action to enable the culprits to be prosecuted in the country.

But in July, the attorney-general, Abu Talib Othman, dropped a bombshell. He said the government had no jurisdiction to try the former BMF officials because the offences were committed outside the country.

When the dirty old man is involved, you can be sure nothing good will result.

ReplyDeleteTurning the probe into a racial issue is typical Mahathir. And disavowing responsibility is also his trademark ala Operasi Lalang.

The difference with Najib is that he was able to stop any meaningful investigation IN MALAYSIA of the 1MDB scandal.

ReplyDeleteAided and abetted by his AG Apandi who said "No evidence 1MDB money misappropriated",

When asked in 2017 whether Malaysia would claim from the US DOJ Kleptocracy Funds Recovery initiative, Najib famously replied Malaysia has nothing to recover because no money was missing from 1MDB.

It took a change of government on May 8 2018 for any real investigation into 1MDB to move ahead.