Bridget Welsh

Published: Apr 15, 2025 11:15 AM

Updated: 1:21 PM

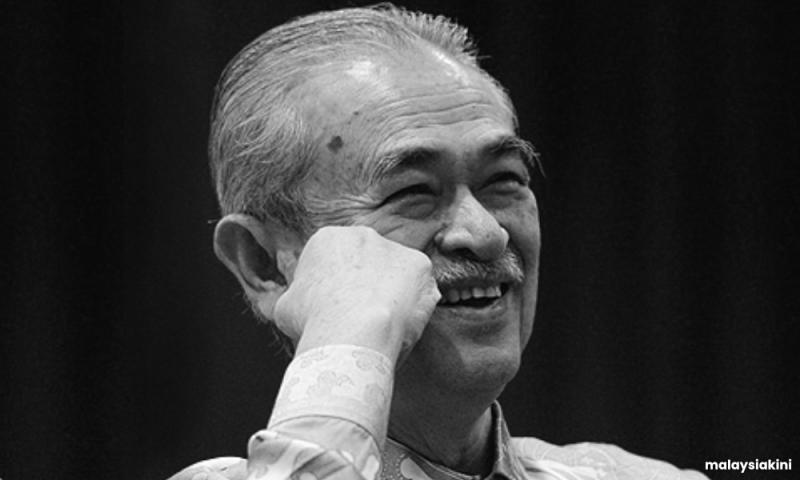

COMMENT | The passing of Malaysia’s fifth prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi marks a moment to recognise his contributions to making Malaysia a stronger, more resilient country.

In the book “Awakening: The Abdullah Badawi Years in Malaysia” which I co-edited with James Chin and included over 31 contributors in 2013, one of the main themes of the collection was that Abdullah left Malaysia transformed for the better; he facilitated conditions that empowered Malaysians and decentralised power.

It was a necessary and welcomed change after 22 years of strongman leadership of Dr Mahathir Mohamad, yet one in which Abdullah’s main challenge was dealing with the legacy issues of his predecessor and an unwillingness of his predecessor to let go of power.

Abdullah’s time in office was one in which he left an indelible legacy, changing views of leadership, reconfiguring power and bringing difficult national problems to the surface.

He was arguably Malaysia’s modern democrat, a man some argue was before his time and others bemoaned his timing. His years in office transitioned Malaysia from strongman rule to a more vibrant democracy, stewarded with decency and dignity and marking his role in the nation’s history.

Abdullah’s humanity

That he was known affectionately as “Pak Lah” speaks to his character. He was an approachable, caring person.

Published: Apr 15, 2025 11:15 AM

Updated: 1:21 PM

COMMENT | The passing of Malaysia’s fifth prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi marks a moment to recognise his contributions to making Malaysia a stronger, more resilient country.

In the book “Awakening: The Abdullah Badawi Years in Malaysia” which I co-edited with James Chin and included over 31 contributors in 2013, one of the main themes of the collection was that Abdullah left Malaysia transformed for the better; he facilitated conditions that empowered Malaysians and decentralised power.

It was a necessary and welcomed change after 22 years of strongman leadership of Dr Mahathir Mohamad, yet one in which Abdullah’s main challenge was dealing with the legacy issues of his predecessor and an unwillingness of his predecessor to let go of power.

Abdullah’s time in office was one in which he left an indelible legacy, changing views of leadership, reconfiguring power and bringing difficult national problems to the surface.

He was arguably Malaysia’s modern democrat, a man some argue was before his time and others bemoaned his timing. His years in office transitioned Malaysia from strongman rule to a more vibrant democracy, stewarded with decency and dignity and marking his role in the nation’s history.

Abdullah’s humanity

That he was known affectionately as “Pak Lah” speaks to his character. He was an approachable, caring person.

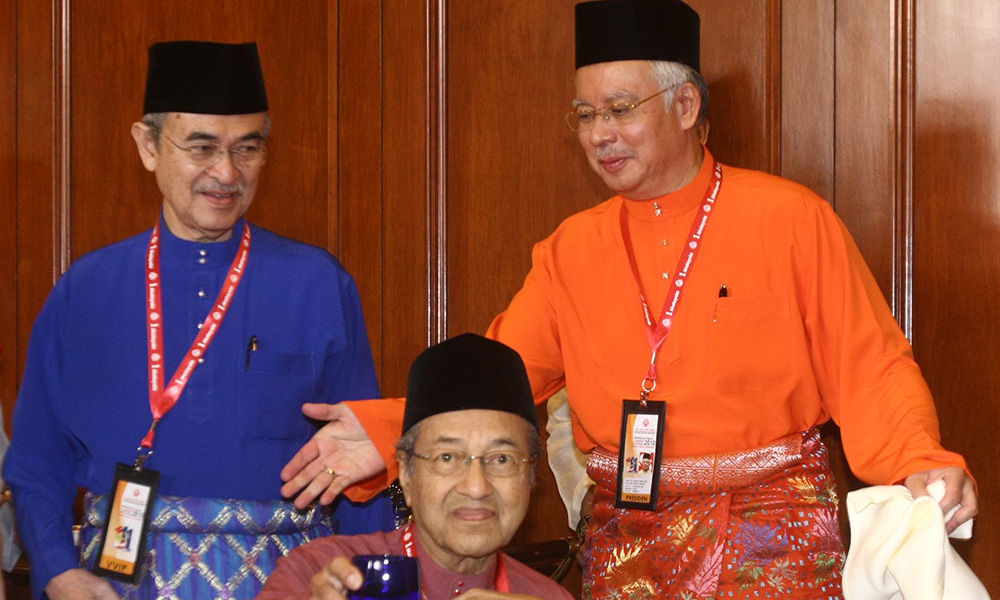

Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (left) with his predecessor Dr Mahathir Mohamad (front) and successor Najib Abdul Razak

Two important political acts stand out:

First, when he was asked about Mahathir (for a lengthy interview published in the Awakening collection), Abdullah chose the high road. He responded:

“Mahathir is very set in his ways. And he believes that his way is the only way. When I tried to do things differently, he believed that I was doing things wrongly. But that is Mahathir.”

When pressed, this was all he would say. Not a single negative word. Not a single attack.

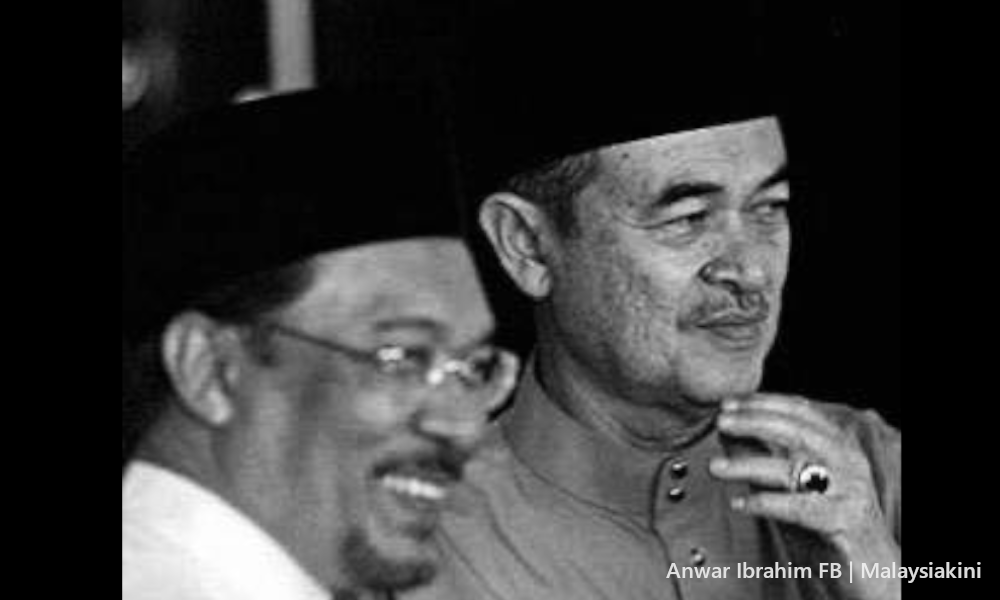

Second, he released Anwar Ibrahim from prison in September 2004, less than a year after assuming office. Abdullah understood the wrong that had been carried out and the impact of being politically targeted.

The years that Abdullah was in the political wilderness in the 1980s after the split in Umno had left a mark on him and his family.

His decision set the country on its future leadership path while showcasing compassion.

Abdullah personified a different type of leader, a man who ignored the lampooning of him as a “sleeping PM” (he had the condition of sleep apnoea), apologised when he arrived often late to meetings, and greeted everyone (including strangers) with openness and a smile.

Two important political acts stand out:

First, when he was asked about Mahathir (for a lengthy interview published in the Awakening collection), Abdullah chose the high road. He responded:

“Mahathir is very set in his ways. And he believes that his way is the only way. When I tried to do things differently, he believed that I was doing things wrongly. But that is Mahathir.”

When pressed, this was all he would say. Not a single negative word. Not a single attack.

Second, he released Anwar Ibrahim from prison in September 2004, less than a year after assuming office. Abdullah understood the wrong that had been carried out and the impact of being politically targeted.

The years that Abdullah was in the political wilderness in the 1980s after the split in Umno had left a mark on him and his family.

His decision set the country on its future leadership path while showcasing compassion.

Abdullah personified a different type of leader, a man who ignored the lampooning of him as a “sleeping PM” (he had the condition of sleep apnoea), apologised when he arrived often late to meetings, and greeted everyone (including strangers) with openness and a smile.

Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (right) and Anwar Ibrahim

He accepted people for who they were, not looking at what they could do for him, aggrandising personal wealth and without the insecurities and biases of other leaders toward other communities.

As Abdullah was comfortable with himself, he was comfortable with others. His genuineness was always evident.

Malaysians then used to portraying a leader without failings, saw a good man wrestling with the demands of a difficult office. In Abdullah they were able to connect, as leaders were not always those above, but a reflection of who they could be as individuals.

Building democracy

Abdullah will be remembered beyond who he was as a person. His actions revived democracy in contemporary Malaysia.

In the 2004 election when he won the highest share of seats for his party Umno and BN for being the “non-Mahathir” and promised change, he used this time to make important reforms.

The judiciary, police, Parliament and bureaucracy were strengthened through new commissions, practices, committees and an emphasis on service respectively. The MACC was created as his administration put in place a blueprint for integrity.

A spiritual man, he introduced the pluralist framework of Islam Hadhari. This was his landmark initiative that to this day remains unclear and was largely ineffective. The consequences were to strengthen political Islam rather than provide a clear path to how to navigate differences over faith.

Here there was a disconnect between Abdullah’s pluralist ideals and a society still traumatised from the wounds of decades of ethnic political mobilisation.

Democrat nevertheless Abdullah pushed further. He harnessed the potential of Malaysians by dispersing power, letting go of control and allowing plural voices to emerge. His years in office were one in which political fear dissipated, and public advocacy expanded.

He actively decentralised power through the creation of corridors for different regions. He recognised the differences of Borneo, which was able to win more recognition and power after the 2008 election.

As Abdullah was comfortable with himself, he was comfortable with others. His genuineness was always evident.

Malaysians then used to portraying a leader without failings, saw a good man wrestling with the demands of a difficult office. In Abdullah they were able to connect, as leaders were not always those above, but a reflection of who they could be as individuals.

Building democracy

Abdullah will be remembered beyond who he was as a person. His actions revived democracy in contemporary Malaysia.

In the 2004 election when he won the highest share of seats for his party Umno and BN for being the “non-Mahathir” and promised change, he used this time to make important reforms.

The judiciary, police, Parliament and bureaucracy were strengthened through new commissions, practices, committees and an emphasis on service respectively. The MACC was created as his administration put in place a blueprint for integrity.

A spiritual man, he introduced the pluralist framework of Islam Hadhari. This was his landmark initiative that to this day remains unclear and was largely ineffective. The consequences were to strengthen political Islam rather than provide a clear path to how to navigate differences over faith.

Here there was a disconnect between Abdullah’s pluralist ideals and a society still traumatised from the wounds of decades of ethnic political mobilisation.

Democrat nevertheless Abdullah pushed further. He harnessed the potential of Malaysians by dispersing power, letting go of control and allowing plural voices to emerge. His years in office were one in which political fear dissipated, and public advocacy expanded.

He actively decentralised power through the creation of corridors for different regions. He recognised the differences of Borneo, which was able to win more recognition and power after the 2008 election.

These changes happened while the economy continued to grow and his administration introduced new ideas for development in areas such as agriculture and investment in human capital.

Inevitably, greater political space led to criticisms as expectations were high. Abdullah’s strength was allowing dialogue and discussion of Malaysia’s problems, as holistic solutions remained largely elusive.

While practising tolerance at the leadership level, groups in society were less so and unwilling to accommodate greater inclusion. Racial politics proved too difficult to manage, leading to the loss of the two-thirds majority in the 2008 election.

Abdullah accepted the results with dignity, setting an important example for democracy. He was later punished for the loss and pushed out of office. His actions served to reaffirm confidence in the electoral process, helping rebuild democracy after decades when it suffered and maintaining political stability at a time of political uncertainty.

A man of his time

Abdullah came into office in 2003 at a moment of tremendous promise for Malaysia and left office less than six years later in 2009, pushed out by those in his own party who were unhappy with his less controlling, more tolerant leadership.

He was a man of his time, a man that showcased a softer, nicer side of Malaysia. He allowed Malaysians to breathe, to find their own footing, to harness their own energy and to set their own agency. Ironically, his weaknesses were his strengths.

Like all of the prime ministers after him, Abdullah grappled with the problems of a rapidly changing, complex society, and often fell short of expectations. He was far from perfect, as was his governance. Yet, it was in the imperfections that made his leadership shine, giving Malaysia space for renewal

What he accomplished was much more important than the gaps – he allowed Malaysians to see themselves, and what they could be.

BRIDGET WELSH is an honorary research associate of the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute, a senior research associate at Hu Fu Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com

The most important decision by Pak Lah was to cancel the crooked bridge with Spore. Toonsie must be secretly glad. Publicly of course he hentam Pak Lah.

ReplyDelete