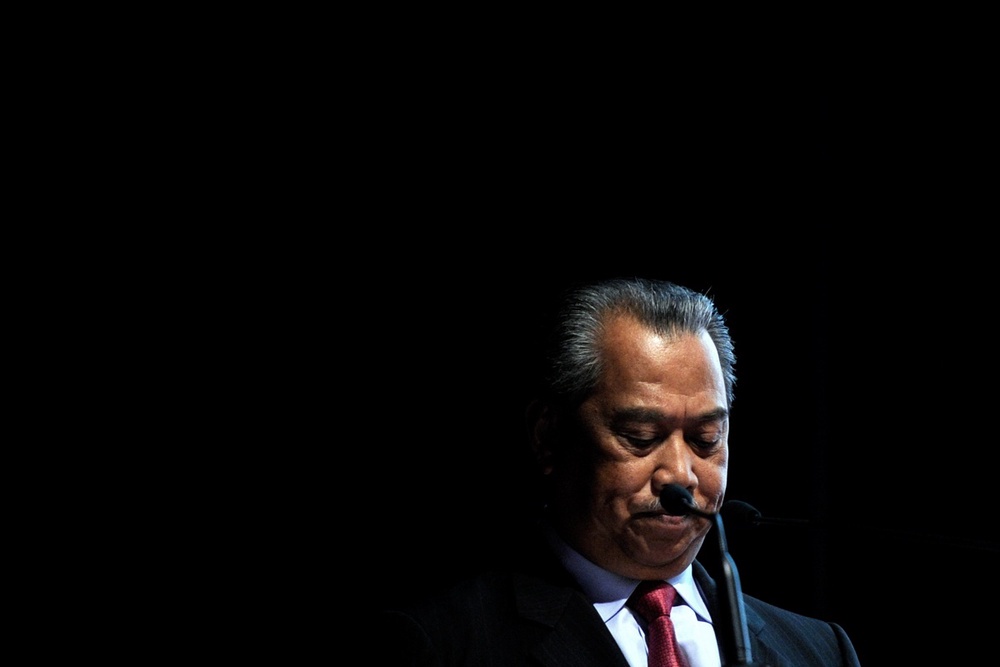

OPINION | Why Muhyiddin’s Fall Was Inevitable — and Necessary

31 Dec 2025 • 10:30 AM MYT

TheRealNehruism

An award-winning Newswav creator, Bebas News columnist & ex-FMT columnist

Image credit : Focus Malaysia

Muhyiddin Yassin’s removal as opposition leader did not begin with the Perlis crisis, nor with internal maneuvering within Perikatan Nasional. It began much earlier—with a fundamental misunderstanding of what leadership demands when one is losing.

When Muhyiddin appeared listless and detached at the Turun Anwar rally in Kuala Lumpur in July, it merely confirmed what had long been evident: he was a man profoundly ill-suited for the role he occupied. The Turun Anwar Rally was supposed to Muhyiddin's event. If Anwar was to turun, as the rally demanded, it was Muhyiddin that would have replaced him. Despite that, Muhyiddin was far from being the man of the rally. Even 100 years old Mahathir, who was not even a part of the opposition camp, outshined Muhyiddin in the rally.

From that moment on, the writing on the wall was that it was only a matter of time before Muhyiddin was to fall .

In truth, the writing on the wall had already been appeared years before that.

Muhyiddin is not without ability. He is competent leader, but he is just not a competent leader in the circumstances that the opposition is in at the present moment. Muhyiddin is best described as a coordinator, caretaker, a manager, a man who can preserve order when conditions are favourable. He is effective at smoothing tensions, balancing factions, and maintaining internal peace—but only when the coalition he leads has already ascended to the top.

To a coalition that is only trying to ascend to the top however, his leadership can only be described as pointless, clueless and lethargic.

That is precisely why his leadership failed.

The Wrong Man for the Wrong Moment

The Malaysian opposition today is not in a position of strength. It is not consolidating power; it is struggling to survive. It faces a government that is in a position of advantage that has increasingly strengthened itself over the past 3 years.

In facing such an opponent from a position of disadvantage, what an opposition requires is not tranquility, but agitation. Not balance, but confrontation. Not administration, but mobilisation. Not a gentleman, but a conqueror.

A losing coalition must be restless. It must feel urgency in its bones. It must be driven by anger, impatience, and a sense that time is running out. Above all, it needs a leader capable of converting frustration into motion.

Muhyiddin could do none of this.

Instead of sharpening the opposition’s edge, he dulled it. Instead of heightening urgency, he imposed calm. Instead of provoking action, he enforced order. What he mistook for stability was, in reality, paralysis.

Harmony as Decay

There is something deeply unnatural about peace in a time of defeat.

Under Muhyiddin, the opposition became oddly serene while steadily losing ground. This serenity did not reassure its members; it alienated them. Rank-and-file leaders could sense decline, yet saw no fightback. Over time, harmony ceased to feel virtuous and began to feel suffocating.

When a leader refuses to channel frustration, that frustration does not disappear. It mutates.

It turns into defiance.

And so, resistance began to emerge—not openly at first, but quietly, locally, and then unmistakably.

Perlis and the Collapse of Authority

The events in Perlis were not an aberration. They were the logical culmination of a leadership vacuum.

When Bersatu leaders in Perlis moved to unseat a PAS chief minister—despite PAS being a principal ally—it was not simply a tactical gamble. It was an act of open insubordination. A declaration that central authority no longer mattered.

What followed exposed the truth Muhyiddin could no longer conceal.

PAS acted decisively, expelling its own representatives without hesitation. Muhyiddin, however, could not bring himself to discipline the Bersatu figures who instigated the revolt.

At that moment, power revealed itself.

Muhyiddin still held titles, but he no longer commanded obedience. He could speak, but his words carried no weight. He could instruct, but his instructions could be ignored with impunity.

A leader who cannot discipline his own party is not a leader at all.

PAS understood this immediately.

The Unnatural Order of Perikatan Nasional

Politics, like nature, has its own hierarchy. Strength gravitates upward. Authority flows from power.

Within Perikatan Nasional, PAS is the dominant force. Bersatu is not. By the natural order of things, PAS should lead.

Yet Malaysian politics exists in a fragile equilibrium where the strongest party often cannot assume leadership without destabilising the nation. This is why DAP, despite being Pakatan Harapan’s most powerful component, ceded leadership to Anwar Ibrahim.

But such arrangements can only survive if the chosen leader possesses sufficient gravitas to naturalise the imbalance.

Anwar succeeded because he brought with him history, charisma, struggle, and authority. He made an unnatural hierarchy feel organic.

Muhyiddin did the opposite.

His weakness did not conceal the imbalance within PN—it magnified it. Every indecision, every failure to act, every compromise made the unnatural order more visible, more intolerable, and more unstable.

Under his leadership, PN drifted into confusion, lethargy, and self-doubt.

Why His Fall Was Inevitable

PAS may have tolerated Muhyiddin at the beginning, hoping he would grow into the role. But patience erodes when defeat becomes habitual—especially when those defeats feel self-inflicted.

Repeatedly, opportunities slipped away. Momentum dissipated. Victories were transformed into losses not through force, but through hesitation.

Eventually, PAS was forced to confront a simple, brutal question:

Why should we respect the authority of a man whose own party no longer does?

There was no answer—because none existed.

And so Muhyiddin’s removal was not a coup, nor a betrayal. It was a correction. A reversion to political reality, an inevitable naturalization of an unnatural order.

A Necessary End

Muhyiddin’s downfall was not tragic. It was instructive.

It demonstrates a timeless truth: leadership is contextual. The skills that preserve peace are not the skills that win battles. A man suited to maintaining order cannot always be the man who overturns it.

By clinging to a role he could not fulfil, Muhyiddin delayed the inevitable—and deepened the dysfunction.

His removal, painful as it may be for Bersatu, is the only way to restore coherence to the opposition. It is the only way to realign leadership with power, authority with strength, and form with function.

In that sense, his fall is not only inevitable.

It is necessary.

The problem PN now faces is they have no leader candidate of sufficient stature to replace Moo.

ReplyDeleteHadi is one foot from meeting Allah, other PAS leaders have their own issues, Hamzah would play 2nd fiddle to PAS.