Malaysia and Singapore have been disputing over the sovereignty of Pulau Batu Puteh as well as islets Middle Rocks and South Ledge, for decades. Recently, Malaysia has announced a Royal Commission of Inquiry into how these maritime features were managed. – Social media pic, January 27, 2024

How Malaysia let Pulau Batu Puteh go

Despite RCI establishment, its findings would not have any impact on world court’s ruling as 10-year timeframe to apply for judgment revision has long passed

How Malaysia let Pulau Batu Puteh go

Despite RCI establishment, its findings would not have any impact on world court’s ruling as 10-year timeframe to apply for judgment revision has long passed

KUALA LUMPUR – Malaysia and Singapore’s dispute over the sovereignty of Pulau Batu Puteh – also known as Pedra Branca – as well as islets Middle Rocks and South Ledge, had lasted decades between Malaysia and Singapore.

With Putrajaya’s recent announcement of a Royal Commission of Inquiry (RCI) into how these maritime features were managed, including Malaysia’s withdrawal of its appeal against a world court’s decision granting sovereignty of only Middle Rocks, Scoop takes a look back on how the issue started, and what led to the RCI.

How it began

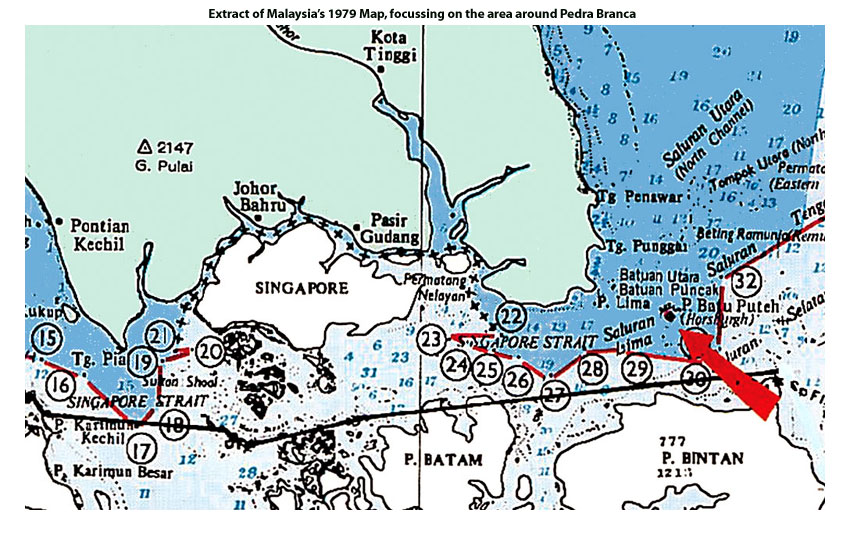

In 1979, Malaysia’s Director of National Mapping published an official map titled “Territorial Waters and Continental Shelf Boundaries of Malaysia’ showing the three features within its territorial waters.

With Putrajaya’s recent announcement of a Royal Commission of Inquiry (RCI) into how these maritime features were managed, including Malaysia’s withdrawal of its appeal against a world court’s decision granting sovereignty of only Middle Rocks, Scoop takes a look back on how the issue started, and what led to the RCI.

How it began

In 1979, Malaysia’s Director of National Mapping published an official map titled “Territorial Waters and Continental Shelf Boundaries of Malaysia’ showing the three features within its territorial waters.

An official map focusing on areas around Batu Puteh published by Malaysia.

The following year, Singapore urged for the map’s correction over Batu Puteh. In years to come, the republic would also dispute the sovereignty of the other islets as well.

The court case between Malaysia and Singapore

In 1989, Singapore suggested referring the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, Netherlands. Malaysia agreed to pursue the case in the world court, in 1994.

A hearing was held in November 2007 for three weeks, and ICJ issued its decision a year later.

Singapore’s argument centred on the following points:

1. Pedra Branca was No man’s land

The republic argued that the island was “terra nulls” or “belonging to no one”, as it was never the subject of a claim by any sovereign entity.

Thus, it rejected Malaysia’s claim that the island was under Johor’s jurisdiction, citing no evidence the Johor Sultanate had exercised authority over the island from 1512 (the Malaccan Empire’s fall) until 1824.

2. The Horsburgh lighthouse was a symbol of S’pore’s lawful ownership

Singapore argued that the lighthouse, which was constructed between 1847 and 1851, meant it possessed the island with the title of a sovereign.

It said the British Crown had obtained the title with legal principles governing the acquisition. After the colonial power left, Singapore said it should continue to maintain the title.

3. Malaysia accepted Singapore’s sovereignty over Batu Puteh

Singapore argued that Malaysia had not challenged Singapore’s activities on Pulau Batu Puteh since 1873, equivalent to over 130 years, indicating that its northern neighbour never regarded the island as part of its territory.

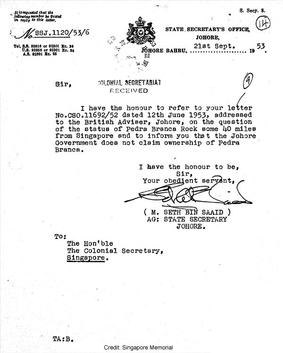

Singapore relied on a letter by Acting State Secretary of Johor to the Colonial Secretary of Singapore dated September 21, 1953, which stated “the Johore Government does not claim ownership of Pedra Branca”.

Based on this, Singapore contended its sovereignty over the island was confirmed and Johor had no title to it.

The following year, Singapore urged for the map’s correction over Batu Puteh. In years to come, the republic would also dispute the sovereignty of the other islets as well.

The court case between Malaysia and Singapore

In 1989, Singapore suggested referring the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, Netherlands. Malaysia agreed to pursue the case in the world court, in 1994.

A hearing was held in November 2007 for three weeks, and ICJ issued its decision a year later.

Singapore’s argument centred on the following points:

1. Pedra Branca was No man’s land

The republic argued that the island was “terra nulls” or “belonging to no one”, as it was never the subject of a claim by any sovereign entity.

Thus, it rejected Malaysia’s claim that the island was under Johor’s jurisdiction, citing no evidence the Johor Sultanate had exercised authority over the island from 1512 (the Malaccan Empire’s fall) until 1824.

2. The Horsburgh lighthouse was a symbol of S’pore’s lawful ownership

Singapore argued that the lighthouse, which was constructed between 1847 and 1851, meant it possessed the island with the title of a sovereign.

It said the British Crown had obtained the title with legal principles governing the acquisition. After the colonial power left, Singapore said it should continue to maintain the title.

3. Malaysia accepted Singapore’s sovereignty over Batu Puteh

Singapore argued that Malaysia had not challenged Singapore’s activities on Pulau Batu Puteh since 1873, equivalent to over 130 years, indicating that its northern neighbour never regarded the island as part of its territory.

Singapore relied on a letter by Acting State Secretary of Johor to the Colonial Secretary of Singapore dated September 21, 1953, which stated “the Johore Government does not claim ownership of Pedra Branca”.

Based on this, Singapore contended its sovereignty over the island was confirmed and Johor had no title to it.

A letter by the acting state secretary of Johor to the colonial secretary of Singapore dated September 21, 1953.

Malaysia’s arguments meanwhile, were as follows:

1. Batu Puteh had never been no-man’s land

Malaysia argued that it had since “time immemorial” held the original title over the island. This meant its ownership “extended beyond memory, records, and tradition”. It had always been a part of Johor, now a Malaysian state.

It also denied any break between the old and new Johor Sultanates.

2. Singapore was only a lighthouse operator

Malaysia argued that the UK and Singapore’s actions in constructing and maintaining the lighthouse only meant they were its operators and not sovereigns of the island.

As such, Johor never ceded the island but only permitted activities by others on it.

3. 1953 letter was unauthorised

Malaysia cited a letter by Singapore’s then-Colonial Secretary on June 12, 1953, addressed to the British Adviser in Johor, which enquired on the status of Pedra Branca. Malaysia held that the contents of this letter indicated Singapore had no conviction that Pulau Batu Puteh was under its territory.

As Singapore relied on the September 21, 1953 letter by the Acting State Secretary of Johor to the Colonial Secretary of Singapore, Malaysia argued that the Johor state secretary lacked the legal capacity to write the letter.

ICJ’s decision

On May 23, 2008, the ICJ, with a bench of 16 judges, ruled that Pulau Batu Puteh was under the sovereignty of Singapore (12 votes), while giving Malaysia sovereignty over Middle Rocks (15 votes).

It did not make a definitive ruling on South Ledge, which it decided belonged to the state “in the territorial waters of which it is located” as the islet fell within overlapping territorial waters. Later, this led to Malaysia and Singapore forming a joint technical committee to delimit the maritime boundaries over South Ledge.

The ICJ ruled Malaysia had been the original owner of the Pulau Batu Puteh since it was established in 1512, but over time, it had allowed the territory to pass to Singapore since Malaysia did not challenge the former’s sovereign title over the island.

The ICJ also rejected Malaysia’s claims about the 1953 letters and supported Singapore’s reliance on the September 21 letter by the Acting State Secretary of Johor that showed Johor understood it had no sovereignty over Pulau Batu Puteh.

It should be noted that before the case, both Malaysia and Singapore had agreed in writing that the ICJ’s ruling would be final and neither would file any plea. Both countries agreed an appeal shall not be made unless new evidence about the case emerges.

Application to review decision and abrupt withdrawal

Nearly a decade after the ICJ’s decision, in February 2017, then-attorney-general Tan Sri Mohamed Apandi Ali said Malaysia had applied to revise the ICJ’s ruling, citing three documents declassified by the UK’s National Archives.

The three documents were the internal correspondence of the Singapore colonial authorities in 1958, an incident report filed in 1958 by a British naval officer, and an annotated map of naval operations from the 1960s.

On June 30 of the same year, Malaysia filed a separate application to request an interpretation of the ICJ’s judgment.

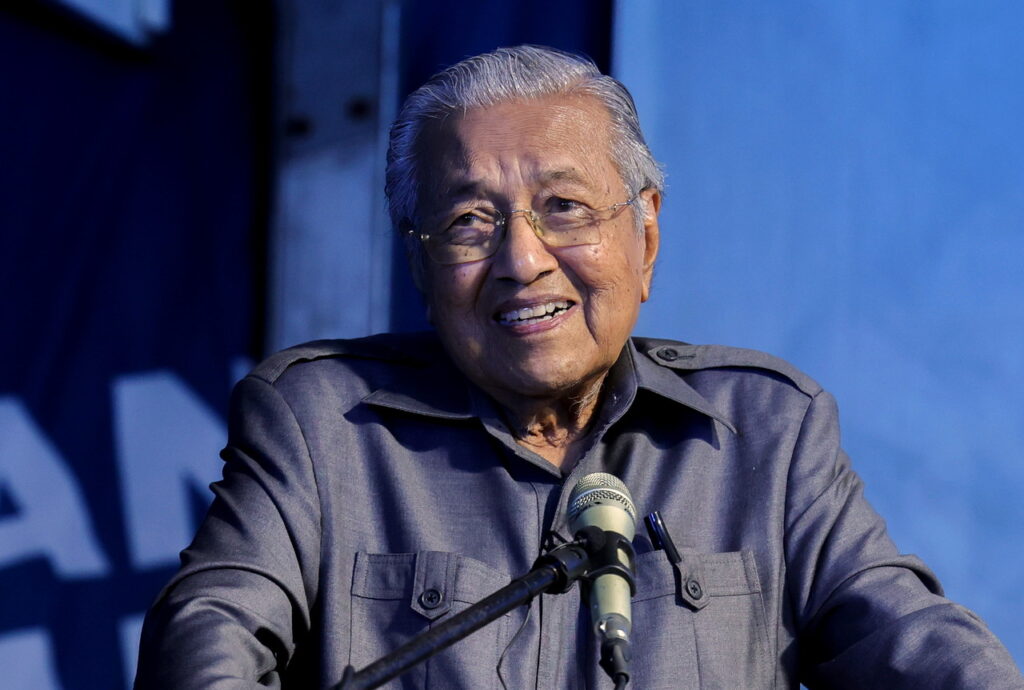

However, on May 30, 2018, the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government under Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad withdrew the applications, two weeks before June 11 when the filings were to be heard at the ICJ. He later said respecting the ICJ’s decision was the main reason for the withdrawal.

The withdrawal meant that Malaysia could no longer challenge Singapore’s sovereignty over Pulau Batu Puteh, as applications for revision must be made within 10 years of the judgment.

Malaysia’s arguments meanwhile, were as follows:

1. Batu Puteh had never been no-man’s land

Malaysia argued that it had since “time immemorial” held the original title over the island. This meant its ownership “extended beyond memory, records, and tradition”. It had always been a part of Johor, now a Malaysian state.

It also denied any break between the old and new Johor Sultanates.

2. Singapore was only a lighthouse operator

Malaysia argued that the UK and Singapore’s actions in constructing and maintaining the lighthouse only meant they were its operators and not sovereigns of the island.

As such, Johor never ceded the island but only permitted activities by others on it.

3. 1953 letter was unauthorised

Malaysia cited a letter by Singapore’s then-Colonial Secretary on June 12, 1953, addressed to the British Adviser in Johor, which enquired on the status of Pedra Branca. Malaysia held that the contents of this letter indicated Singapore had no conviction that Pulau Batu Puteh was under its territory.

As Singapore relied on the September 21, 1953 letter by the Acting State Secretary of Johor to the Colonial Secretary of Singapore, Malaysia argued that the Johor state secretary lacked the legal capacity to write the letter.

ICJ’s decision

On May 23, 2008, the ICJ, with a bench of 16 judges, ruled that Pulau Batu Puteh was under the sovereignty of Singapore (12 votes), while giving Malaysia sovereignty over Middle Rocks (15 votes).

It did not make a definitive ruling on South Ledge, which it decided belonged to the state “in the territorial waters of which it is located” as the islet fell within overlapping territorial waters. Later, this led to Malaysia and Singapore forming a joint technical committee to delimit the maritime boundaries over South Ledge.

The ICJ ruled Malaysia had been the original owner of the Pulau Batu Puteh since it was established in 1512, but over time, it had allowed the territory to pass to Singapore since Malaysia did not challenge the former’s sovereign title over the island.

The ICJ also rejected Malaysia’s claims about the 1953 letters and supported Singapore’s reliance on the September 21 letter by the Acting State Secretary of Johor that showed Johor understood it had no sovereignty over Pulau Batu Puteh.

It should be noted that before the case, both Malaysia and Singapore had agreed in writing that the ICJ’s ruling would be final and neither would file any plea. Both countries agreed an appeal shall not be made unless new evidence about the case emerges.

Application to review decision and abrupt withdrawal

Nearly a decade after the ICJ’s decision, in February 2017, then-attorney-general Tan Sri Mohamed Apandi Ali said Malaysia had applied to revise the ICJ’s ruling, citing three documents declassified by the UK’s National Archives.

The three documents were the internal correspondence of the Singapore colonial authorities in 1958, an incident report filed in 1958 by a British naval officer, and an annotated map of naval operations from the 1960s.

On June 30 of the same year, Malaysia filed a separate application to request an interpretation of the ICJ’s judgment.

However, on May 30, 2018, the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government under Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad withdrew the applications, two weeks before June 11 when the filings were to be heard at the ICJ. He later said respecting the ICJ’s decision was the main reason for the withdrawal.

The withdrawal meant that Malaysia could no longer challenge Singapore’s sovereignty over Pulau Batu Puteh, as applications for revision must be made within 10 years of the judgment.

On May 30, 2018, the Pakatan Harapan government led by Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad withdrew the applications, two weeks before the filings were to be heard at the ICJ. – Bernama pic, January 27, 2024

What’s the big deal about Pulau Batu Puteh?

Appearing as just a group of rocks in the middle of the sea, Pulau Batu Puteh and its islets are in a strategic location.

Besides being a spot for fishermen Johor Menteri Besar Datuk Onn Hafiz Ghazi has said the island was strategically located on the main route for trading vessels through the Malacca Strait and South China Sea.

After the dispute was settled, Singapore said it would carry out development works on the island to enhance the nation’s maritime safety and security, on top of improving search and rescue capabilities in the area.

This would see about 7ha added beyond the island’s original 0.86ha.

In February 2023, however, Singapore had agreed to halt reclamation on the island, according to Malaysian Foreign Deputy Minister Datuk Mohamad Alamin as work to finalise maritime boundaries was still ongoing.

Political fallout

Dr Mahathir’s decision to withdraw Malaysia’s application to review the ICJ’s ruling brought political backlash.

Umno, which was in the opposition when Dr Mahathir was prime minister of the PH government, highlighted the loss of Malaysia’s sovereignty.

On July 3, 2019, Apandi said Dr Mahathir had decided to withdraw Malaysia’s application without consulting him as the attorney-general, or the cabinet.

On September 13, 2021, a 45-year-old man named Mohd Hatta Sanuri filed a suit against the prime minister and Malaysian government, seeking an explanation for the withdrawal.

On October 13, 2022, then-prime minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob said there was a possibility of negligence by Dr Mahathir in withdrawing the applications.

On October 29, 2021, Ismail Sabri announced a special task force, aimed at reviewing the actions and legal issues over the withdrawal.

Also in 2022, Onn Hafiz urged the government to take legal action against the parties that led to Malaysia losing Batu Puteh. He said local fishermen had suffered tremendous loss of income, adding that the island often acted as a shelter and resting spot for the fishermen.

More recently, on January 23 last year, then-attorney-general Tan Sri Idrus Harun said the government’s decision to withdraw the review application was “irregular and inappropriate”.

What’s the big deal about Pulau Batu Puteh?

Appearing as just a group of rocks in the middle of the sea, Pulau Batu Puteh and its islets are in a strategic location.

Besides being a spot for fishermen Johor Menteri Besar Datuk Onn Hafiz Ghazi has said the island was strategically located on the main route for trading vessels through the Malacca Strait and South China Sea.

After the dispute was settled, Singapore said it would carry out development works on the island to enhance the nation’s maritime safety and security, on top of improving search and rescue capabilities in the area.

This would see about 7ha added beyond the island’s original 0.86ha.

In February 2023, however, Singapore had agreed to halt reclamation on the island, according to Malaysian Foreign Deputy Minister Datuk Mohamad Alamin as work to finalise maritime boundaries was still ongoing.

Political fallout

Dr Mahathir’s decision to withdraw Malaysia’s application to review the ICJ’s ruling brought political backlash.

Umno, which was in the opposition when Dr Mahathir was prime minister of the PH government, highlighted the loss of Malaysia’s sovereignty.

On July 3, 2019, Apandi said Dr Mahathir had decided to withdraw Malaysia’s application without consulting him as the attorney-general, or the cabinet.

On September 13, 2021, a 45-year-old man named Mohd Hatta Sanuri filed a suit against the prime minister and Malaysian government, seeking an explanation for the withdrawal.

On October 13, 2022, then-prime minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob said there was a possibility of negligence by Dr Mahathir in withdrawing the applications.

On October 29, 2021, Ismail Sabri announced a special task force, aimed at reviewing the actions and legal issues over the withdrawal.

Also in 2022, Onn Hafiz urged the government to take legal action against the parties that led to Malaysia losing Batu Puteh. He said local fishermen had suffered tremendous loss of income, adding that the island often acted as a shelter and resting spot for the fishermen.

More recently, on January 23 last year, then-attorney-general Tan Sri Idrus Harun said the government’s decision to withdraw the review application was “irregular and inappropriate”.

Truth is , Pedra Branch was let go to Singapore a long time ago by a combination of actions and inactions. Culminating in the inept Malaysian case conducted during the ICJ case in The Argue.

ReplyDeleteThe attempt to blame the whole case failure on Tommy Thomas was Perikatan Nasional Government bullshit