This Is Just The Beginning – These Charts Show The Impact Of The BRICS Expansion, And How 6 New Members Were Selected

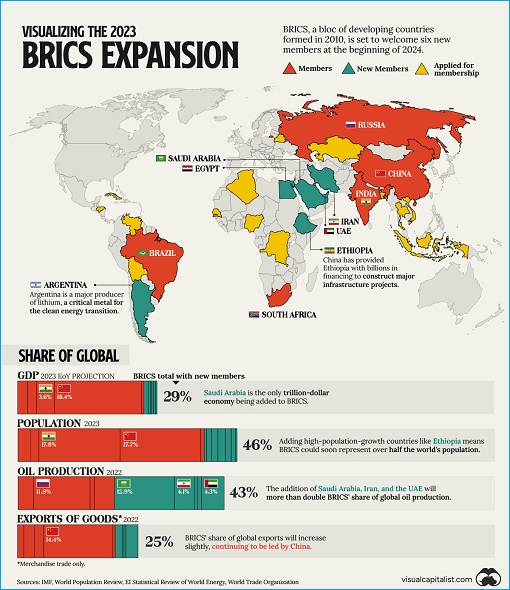

BRICS has expanded to include Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, Ethiopia and Argentina. Following the 15th annual BRICS summit in Johannesburg, South Africa last week, the bloc of five major emerging economies – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – decided to admit the additional 6 new members, effective January 1, 2024.

Pro-Western news media, as expected, have played down – even laughed – at the enlarged bloc as nothing but merely a symbolic achievement. The “historic” expansion was belittled as a group of mixture of autocratic nations with middle-income and developing democracies, members with clueless goals, and a bloc of anti-western nations that are facing dire economic problems.

So, should the Group of Seven (G-7), popularly known as the club of rich nations, ignore and dismiss the latest BRICS expansion? Nothing happens by coincidence; therefore, BRICS did not expand for the sake of expansion. After all, this is the bloc’s first expansion in 13 years. And the door is left open as dozens more countries have voiced interest in joining the group.

Politically, the expansion clearly shows the BRICS’ intention to spread its influence in the Global South – largely refers to countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. There are reasons why those six countries are chosen. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva had personally lobbied for neighbour Argentina, while Egypt has close commercial ties with Russia and India.

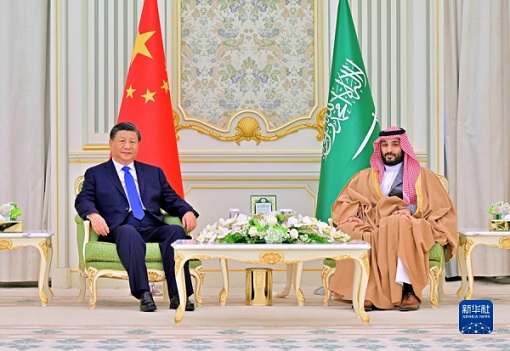

On the other hand, Russia and Iran share a common enemy, thanks to U.S.-led sanctions against both nations. In the same breath, China has just brokered a peace deal between bitter rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia, something unimaginable to the Western power. The inclusion of Saudi and UAE in BRICS also means the oil powers are drifting away from the United States’ orbit.

Ethiopia, was surprisingly admitted to the club when other countries have applied, but not successful. For example, why this African country was chosen, but not Indonesia? As the only African country to be admitted this round since the BRICS first expanded to admit South Africa in 2010, Ethiopia was selected based on geo-economic, geostrategic and geopolitical reasons.

Ethiopia, a country with one of the fastest-growing economies at over 5% annually, hosts the headquarters of the African Union (the continental union consisting of 55 member states of Africa). It is also hosts the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and its capital, Addis Ababa, is known as the continent’s diplomatic capital, even though its economy is less than half the size of South Africa.

In reality, with the exception of Nigeria and Kenya, most of the African countries are facing deteriorating relations with the West as a result of civil wars, resulting in pressure due to human rights. Having developed strong economic ties with the continent, China and India are now Africa’s two largest single trading partners, giving it even more reason to admit another African country.

While some countries, such as Ethiopia, Saudi, UAE and Egypt, wanted to hedge their bets so that they can fall back to BRICS in the event the U.S. gives them “troubles”, new BRICS members like Iran suddenly found itself to be “no longer isolated”. That makes Iran even more depended on “big brothers” China and India – effectively sending a message to the U.S. that Iran is being protected.

Economically, the new bloc will represent about 46% of the world population – accounting for 29% of the world’s GDP (gross domestic product in nominal terms) and 37% of global GDP (based on purchasing power parity). On the surface, the new six members might not add too much value to BRICS, as Saudi is the only trillion dollar economy among the new entrants.

But to China and Russia, the crown jewel of the expansion is the inclusion of Saudi, Iran, UAE and Egypt – the major players in the Middle East. Besides Russia, all of the other BRICS countries are non-energy producing countries before the expansion. Now, they can reduce their vulnerability as Washington can no longer weaponize Saudi to threaten Beijing, let alone the Kremlin.

Iran holds the world’s second-largest gas reserves and a quarter of the oil reserves in the region. The access to BRICS will allow it to strengthen its economic and political ties with non-Western powers. On top of selling discounted oil to China, it can boost its economic ties with Beijing, as well as deepening security and military partnership with Russia.

The inclusion of Saudi and the UAE, two of the world’s largest energy suppliers and financial heavyweights in the Middle East, was done to disrupt the U.S. world order. Although both Gulf nations are still American allies, and will continue to rely on the U.S. to protect them militarily, they also wanted the membership in the BRICS to balance out its traditional partnerships with the U.S.

Dubai, flushed with Russian money and oil, is home to many Russian super-rich after Western sanctions hit the country following the invasion of Ukraine. Eager to diverge from American interests, the UAE has seen its trade with China and India flourish. Like Saudi, the Arab nations wanted the best of both worlds – protection from the U.S. and commerce with China.

Crucially, a new member like Egypt has learned the hard way of relying on the U.S. dollar. The strengthening of the greenback has caused inflation and ballooning national debts. Within BRICS, Egypt could trade in local currency. Likewise, China does not need to do heavy lifting as de-dollarization could begin significantly with Saudi joining the club.

On March 30, Brazil announced a deal with China to ditch the U.S. dollar when paying each other for goods. The deal will enable China, the top rival to American economic hegemony, and Brazil, the biggest economy in Latin America, to conduct their massive trade and financial transactions directly – exchanging Yuan for Real and vice versa instead of going through the greenback.

But de-dollarization was not confined to merely BRICS members. In another astonishing move, the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange announced on March 30 that it completed its first Yuan-settled trade for liquid natural gas (LNG) between China’s National Offshore Oil Corporation and France’s TotalEnergies. Yes, even France has begun using the Chinese currency.

The first-ever deal in the Renminbi Yuan currency between the Chinese and French energy companies involved 65,000 tons of LNG imported from the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The trade marks a major step in Beijing’s attempts to challenge the “petrodollar” with the alternative “petroyuan”, something which China introduced in 2018 to give the U.S. dollar a bloody nose.

Using Yuan is not the only way to dump the U.S. dollar. Brazil and Argentina have discussed the creation of a common currency for the two largest economies in South America. The UAE and India are in talks to use Indian Rupees to trade non-oil commodities in a shift away from the dollar. Trade between India and Malaysia can now be settled in the Indian currency too.

However, this is just the beginning. There are over 40 countries that have expressed interest in joining BRICS. Exactly they wanted to join the bloc? After the U.S. froze Russia’s US$630 billion foreign reserves, many countries fear they could suffer the same “daylight robbery”, therefore the need to diversify from the dollar. Saudi understood very well that their US$430 billion foreign reserves could vanish one day if the U.S. suddenly imposes sanctions on them.

U.S. lawmakers have urged President Joe Biden to teach Saudi a lesson by revoking the sovereign immunity that protects OPEC members and allied oil-producing nations from antitrust lawsuits. On May 5, 2022, the U.S. passed the NOPEC bill – No Oil Producing and Exporting Cartels – a new tool specially designed to tackle high fuel prices associated with OPEC+.

If Washington weaponizes NOPEC, the U.S. attorney general will be empowered to sue the oil cartel or its members, such as Saudi Arabia and its allies in the Middle East, in federal court. Once invoked, however, it could trigger dangerous consequences whereby the U.S. and Saudi relationship could explode beyond repair, including economic and financial sanctions.

Russia has openly said it doesn't like Rupees, and India doesn't like Rubles much.

ReplyDeleteWhile using each other's currencies can be useful in Counter-trades, most won't hang on to the surplus in those currencies.

India troops have killed China troops, and China troops have killed India troops in recent events. Do they want to use Yuan and Rupees respectively ?

Wakakaka…

DeleteR u parading yr inconsequential know-nothing fart of international commercialised trading mechanism?

Check yr f*cked capitalist doctrine - profit overrules every other consideration - before u fart AGAIN!