Tuesday, August 19, 2025

Russia’s “Monroe Doctrine”: After Ukraine, Who Will Be Next In “Firing Line” As Putin Vows To Defend Russian Speakers?

By Sumit Ahlawat

In his high-stakes Alaska summit with US President Donald Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin has spelled out his list of non-negotiable demands for ending his three-and-a-half-year-old war in Ukraine.

The list includes three kinds of demands: No NATO membership for Ukraine, which by extension means an end to NATO’s eastward expansion, territorial gains for Russia, including Ukraine’s withdrawal from Donbas, and formal recognition of Crimea as Russian territory, and religious and cultural rights for Russian speakers in Ukraine.

While most of the commentators, including in the US, the EU, and Ukraine itself, have focused on the territorial aspect of Putin’s demands and how his forceful changing of international borders hurts at the very heart of rules-based international order and the UN charter, it is the third aspect of Putin’s demands – a guarantee for safeguarding the religious and cultural rights for Russian speakers in Ukraine – which is most dangerous.

With this demand, Russia is perpetually establishing itself as a party to internal political dynamics within Ukraine. If Moscow ever feels that the religious and cultural rights of Russian speakers are threatened in Ukraine, as Putin claimed he felt first in 2014 and then again in 2022, which forced him to invade Ukraine, he might take the same step again, notwithstanding the security guarantees given to Kyiv.

This, in effect, puts the onus on Kyiv for not provoking Moscow to invade it again.

In fact, not just Ukraine, this logic – that Russia is a natural protector and guarantor of religious and cultural rights for Russian speakers all over the world, especially in former Soviet Union states, and can use the full spectrum of diplomatic/economic/military means for their protection – establishes Russia as a party not just in the internal politics of Ukraine but in a host of former Soviet Union states from Lativia to Kazakhstan, and from Moldova to Estonia.

Vladimir Putin and Russia Map. Edited Image.

Vladimir Putin and Russia Map. Edited Image.This, to my mind, will be the most long-lasting result of the Ukraine War and Moscow’s biggest victory, not the land Russia will gain in Eastern Ukraine.

Russia’s Own Monroe Doctrine

In effect, this would amount to international recognition of a concept Putin has been parroting for some years—Near Abroad or “Blizhnee Zarubezhe” in Russian.

This term refers to the independent republics that emerged from the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The term is used to describe the countries that border Russia, and it is associated with Russia’s asserted right to exert significant influence in this region.

The concept is sometimes compared to the Monroe Doctrine, which defined the United States’ sphere of influence in the Americas.

In a significant March 2023 paper – “The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation,” – by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Moscow explained the term ‘Near Abroad’ in the following terms.

The section entitled “Near Abroad” set a goal of “establishing an integrated economic and political space in Eurasia in the long term.”

The section’s main emphasis was on deterring the influence of other states by “preventing and countering unfriendly actions of foreign states and their alliances, which provoke disintegration processes in the near abroad and create obstacles to the exercise of the sovereign right of Russia’s allies and partners to deepen their comprehensive cooperation with Russia.”

Furthermore, in August 2008, shortly after Russia’s five-day war with Georgia, when Russia openly revised the 1991 settlement of post-Soviet states’ borders for the first time, then Russian Vice President Dmitry Medvedev explicitly argued for Russia’s right to a sphere of influence in its neighborhood (Near Abroad).

He said, “Russia, just like other countries in the world, has regions where it has its privileged interests. In these regions, there are countries with which we have traditionally had friendly cordial relations, historically special relations.”

The Ukraine War and the peace agreement can set this concept of ‘Near Abroad,’ first advanced during the Georgia War, in stone and give it international sanction.

Russian-Speakers In Former Soviet States

According to Putin, discrimination against Russian speakers in Eastern Ukraine was one of the main causes of the war. Before the war started, there were approximately 30% Russian speakers in Ukraine.

In the years preceding the 2022 invasion, Ukraine had taken specific steps that could be termed discriminatory, even openly hostile, to the Russian language.

In 2019, the Ukrainian parliament passed a law that gave special status to the Ukrainian language and made it mandatory for public sector workers, a move Russia described as divisive.

Earlier in September 2018, the Lviv Oblast Council introduced a ban on the public use of the Russian-language cultural products (movies, books, songs, etc.) throughout the Lviv Oblast until the full cessation of the occupation of Ukraine’s territory.

This discriminatory language policy of Ukraine was criticised even by civil rights groups, Human Rights Watch, and the Venice Commission.

Moscow cited these discriminatory laws as justification for its invasion of Ukraine.

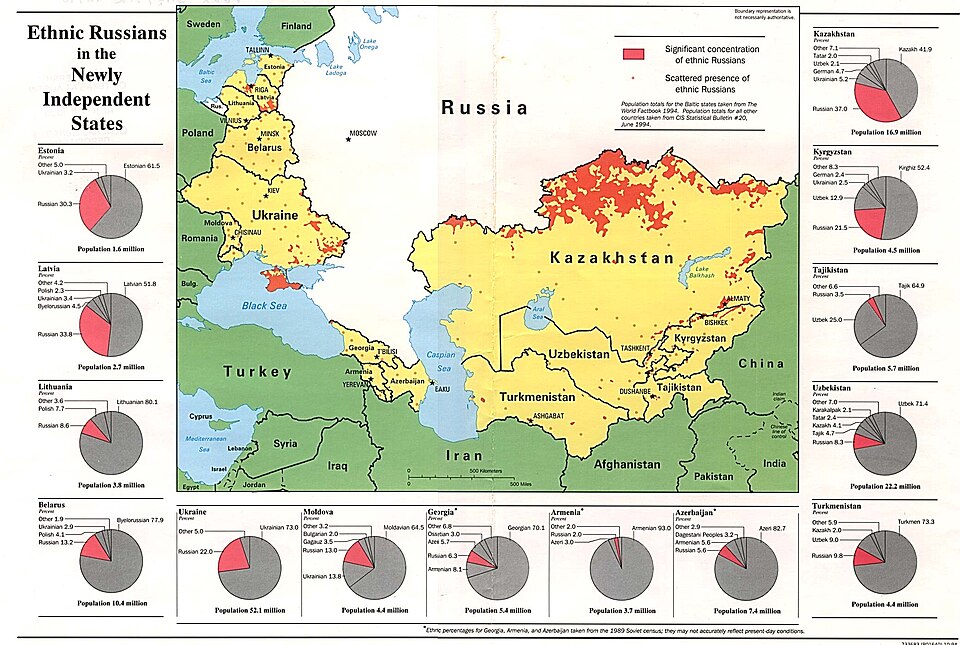

However, Ukraine is not the only former Soviet state with a significant Russian-speaking minority.

In Belarus, nearly 70-80% of the population is Russian-speaking. In the Baltic states as well, the Russian-speaking population is a significant minority.

Ethnic Russian in former Soviet states. Credits Wikipedia.

In Latvia, nearly 33% of the population is Russian-speaking. In Estonia, the number is almost 30 %. In Kazakhstan, 20 to 25% of the population is Russian-speaking. And, in Moldova and Kyrgyzstan, nearly 10% of the population is Russian-speaking.

Moscow wants to be recognized as the natural protector of the cultural rights of these people in Russia’s ‘Near Abroad’.

In Latvia, nearly 33% of the population is Russian-speaking. In Estonia, the number is almost 30 %. In Kazakhstan, 20 to 25% of the population is Russian-speaking. And, in Moldova and Kyrgyzstan, nearly 10% of the population is Russian-speaking.

Moscow wants to be recognized as the natural protector of the cultural rights of these people in Russia’s ‘Near Abroad’.

Russian-Speakers In Former Soviet States

These Russian-speaking minorities in the former Soviet states serve as an important pressure point that Russia holds and can be used as justification for Moscow’s interference in the internal affairs of these countries.

In fact, Russia has a term to describe these people – ‘Compatriots Living (Near) Abroad’. Essentially, Moscow describes them as fellow Russian citizens who are living in other countries. And, since they are Russian citizens, Moscow has every right to speak for them and take any action to protect their identity, rights, and interests.

Putin has always been vocal about protecting these people.

In December 2014, nearly six months after the annexation of Crimea, during his Annual Address to the Federal Assembly, Putin said: “If for many European countries national pride is a long-forgotten concept and sovereignty is too much of a luxury, for Russia, true sovereignty is absolutely necessary for survival. This is especially true when it comes to protecting our compatriots abroad.”

In October of the same year, during his speech at the Valdai Discussion club, Putin said, “We will continue to protect the rights of our compatriots abroad, using the entire spectrum of available means, from political and economic to humanitarian operations and the right to self-defense.”

In 2012, during his meeting with Russian ambassadors, Putin said: “We must consistently protect the interests of our compatriots living abroad, promote their active involvement in ties with Russia, and facilitate the preservation of their cultural and linguistic identity.”

In 2015, in an interview with German ARD Television, Putin said: “We are not going to abandon our compatriots. Wherever they are, we will support them and ensure their rights are respected.”

Putin has also spoken about these ‘compatriots living abroad’, even in the UN.

In 2015, during his speech to the UN General Assembly, Putin said: “We consider it our duty to support our compatriots abroad, to ensure their rights to preserve their identity, language, and culture, and to protect them from discrimination.”

Another factor working in Russia’s favor is that many of these Russian-speaking minorities are concentrated in some specific regions of these countries. Just like Russian speakers were concentrated in the Donbas region of Ukraine, within Kazakhstan, most of the Russian speakers are concentrated in the northern part of the country, close to the Southern Russian border.

Similarly, in Estonia, they are concentrated in the Ida-Viru region and the Latgale region in Latvia.

These concentrated Russian speaking populations can help Russia in destabilizing these regions in the future.

These quotes by Putin about ‘compatriots living abroad’ go back more than a decade, and were expressed even at the UN, showing Russia’s consistent efforts to be recognized as the sole spokesperson for these people.

However, the Ukraine peace agreement could go one step further and give legal and international sanctity to Russia’s claims of speaking in the name of these Russian-speaking minorities living in former Soviet states.

Sumit Ahlawat has over a decade of experience in news media. He has worked with Press Trust of India, Times Now, Zee News, Economic Times, and Microsoft News. He holds a Master’s Degree in International Media and Modern History from the University of Sheffield, UK.

Bloodymir Rasputin must return the 35,000 Ukrainian children kidnapped and held hostage, to be “Russified”. I thot they already speak Russian, what’s there to Russify?

ReplyDeleteBoth Al Jezebel and The Guardian of the Truth say so, so this must be True.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/27/russia-ukrainian-children-abduction-war-crime

https://www.aljazeera.com/amp/news/2025/6/10/russia-ukraine-children-war

Ooop… mfer spread s urban legend no end, with a twist to theguardian's content!

DeletePlaying on the gullible gullies' mentality of yr fart.

1945-1990 “Stalin Doctrine” already failed. USSR collapsed. Move On. Join Belt You Down My Road.

ReplyDeleteso?

DeleteIf Bloodymir Rasputin can keep Ukrainian territory it won thru war then Isaac can keep territory it wins thru war too. Must be Same Same.

ReplyDeleteboth wars have not ended yet.

DeleteWho to keep what r still open.

Keep that in mind, mfer!

Has the useless UN declared Donbas as “occupied territory” and Bloodymir Rasputin is illegally building Russian settlements, kidnapping and holding hostage 35,000 Ukrainian children, re-populating the region with Russians?

ReplyDeleteBe consistent lah UN. That’s what you have said about “Palestine”.

Albo and Penny please announce that Oz will recognize pre-2022 Ukraine-Russia border and that 2014 Crimea seizure was illegal.

majority of the residents of Donbass, Ukraine r Russian speaking. They have much closer link with Russia than with the western Ukraine.

DeleteThat's also why they r been suppressed & criminalized as Ukrainians, forcingly them to seceding from Ukraine & join Russia.

UN has NO says about the atrocities happened in Donbass bcoz yr idol Yank kept veto those voices!

The size of “occupied territory” of Donbas and Crimea is 200 times the size of West Bank and Gaza. The number of civilians and soldiers killed is also many times more. Hari2 misai and rocket and drone bom Ukraine non-stop.

ReplyDeleteBut the world and UN focus only on Gaza Gaza Gaza. No protes in Harvard, Columbia, Londonstan or Sydney Harm-ass Bridge for poor Ukraine.

Why?

Bcoz what happened between Russia & Ukraine is different from those between Palestine & zionist state!

DeleteWhy is there no chant “From the (Dneiper) River to the (Black) Sea, Crimea will be Free?

ReplyDeleteditto above

DeleteA recipe for endless wars of Russian conquest, unless they are stopped in Ukraine.

ReplyDeleteMfer, u ain't Zbigniew Brzezinski, who could predict accurately about the tripartite rapprochement of China, Russia & Iran in 1997 (~ 28yrs ago).

Delete