Too Little Too Late – Bank Negara Raises Interest Rate To Rescue Tumbling Ringgit Under Pretext Of Fighting Inflation

As expected, Bank Negara Malaysia (Central Bank of Malaysia) has finally raised its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points today (May 11). With the increase, the first since the rate reached a record low of 1.75% in July 2020, the effective OPR (overnight policy rate) is now 2.00%. However, at the same time, the timing of the hike is both surprising and unexpected.

As explained previously, the hike has been expected, largely because of three factors – last week’s decision by U.S. Federal Reserve to raise interest rate by 50 basis points (and more to come), sagging economy and plunging Ringgit. Unless the Malaysian central bank and the Ismail Sabri government have been telling lies, this has very little to do with inflation.

At the same time, the rate hike is both surprising and unexpected, so much so it caught analysts and economists off guard. A survey by Bloomberg showed out of 19 economists, only 5 had predicted a rate hike. The rest had forecast that Bank Negara will leave the rates unchanged – at least till the next quarter before the central bank raises the rate to fight inflation.

Chua Han Teng, economist at DBS who had predicted no change to the interest rate, said – “We think that Bank Negara Malaysia would want to see a durable economic recovery from the pandemic amid growing downside risks before normalising policy in early 2H22 (second half of 2022), despite already having signalled the prospects to withdraw significant monetary support.”

Over the past 2 years during Covid-19 pandemic, the country’s interest rate was reduced by a total of 125 basis points to a historic low in attempts to cushion struggling economy, made worse by the clueless and incompetent backdoor government of Muhyiddin Yassin in mishandling the pandemic and mismanagement of economy. Muhyiddin was toppled in August last year.

In justifying the interest rate, the central bank said – “The inflation outlook continues to be subject to global commodity price developments, arising mainly from the ongoing military conflict in Ukraine and prolonged supply-related disruptions, as well as domestic policy measures on administered prices”. It also said the latest indicators showed that economic growth was on a firmer footing.

That’s a gibberish statement to blame an increasing inflation in commodity prices, which in turn was caused by supply chain problems, which in turn was contributed by Ukraine War. First thing first – was there an inflation crisis to begin with? In March, Malaysia said its inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI), rose 2.2% in February 2022 from a year ago.

Even though there was an increase, the inflation rate (2.2%) in February represented a deceleration, marking the slowest price increases in 6 months. UOB Global Economics and Markets Research, while maintaining its 2022 full-year inflation forecast at 3%, said Malaysia’s headline inflation in February has defied its estimation of 2.5%, largely due to fuel subsidies.

MIDF Research, on the other hand, said the deceleration in Malaysia’s CPI (Consumer Price Index) in February was attributable to the slower non-food inflation at 1.5% year-on-year. MIDF maintained its forecast for 2022 headline inflation at 2.1%. The Malaysian Industrial Development Finance was one of research firms that had predicted the central bank would maintain the interest rate until the second half of 2022.

Last month, the Statistics Department revealed that Malaysia’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) in March 2022 – unexpectedly – was at 2.2%, unchanged from February’s six-month low figure and less than market expectations of 2.3%. Still, it surpassed the average inflation for the “January 2011-March 2022 period” which stood at 1.9%. The increase was blamed on food and non-alcoholic beverages.

Chief statistician Mohd Uzir Mahidin said – “Food inflation remained as a major contributor to inflation. The 4.0% growth in the food and non-alcoholic beverages group was largely due to an increase in the food at home component which rose by 4.3% compared to 4.1% recorded in February 2022″. In addition, he said “meat” remained the main contributor to the food inflation, rising by 7.6% in March 2022.

However, it’s also true that food prices have increased the most since December 2017 ahead of the fasting month of Ramadan (4.0% in March compared to 3.7% in February). Compared to America, however, Malaysia appears to have done an incredible job. The U.S. inflation rate accelerated to 8.5% in March, after hitting 7.5% in January and 7.9% in February – the highest in 40 years.

In fact, in its monetary policy statement after unexpectedly raising the interest rate by 25 basis points today, Bank Negara Malaysia said that headline inflation is projected to average between 2.2% – 3.2% in 2022. So, exactly why the country was so nervous that it had to raise the interest rate at a time when the inflation seems not only under control, but was at such low level (compared to the U.S.)?

If you believe the government’s dubious inflation figures, then perhaps you should also believe that Britney Spears is still a virgin. Every Malaysian, regardless of race and religion, knew that food price did not increase by merely 4% because that percentage would translate to an increase of just RM0.30 for a plate of RM7 economic rice, for example. But was that what happened on the ground?

Either the government has lied about its inflation statistics all this while, or the interest rate hike was due to something else. And you can bet your last penny that it has everything to do with the local currency – Ringgit – which has been dropping like a rock. Since the unelected Ismail Sabri government took over the country in August last year, the Ringgit has tumbled to a 2-year low.

In fact, the Ringgit depreciated to as low as 4.3856 to a US dollar today – till the central bank dropped the bombshell. This means in less than 10 months since the clueless and incompetent turtle-egg man became the prime minister, the currency has lost 6.2% of its value, dropping from 4.13 to 4.3856 on Wednesday (May 11). The Ringgit immediately jumped 0.1% after the rate hike.

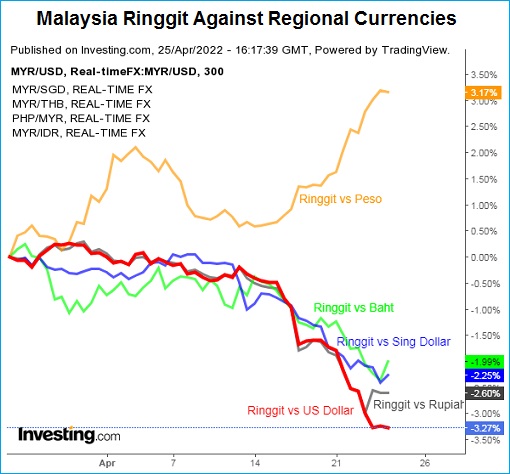

As much as Prime Minister Sabri likes to blame the U.S. Federal Reserve, he cannot explain why the Ringgit is the worst currency against the dollar when compared to regional currencies like Singapore Dollar, Indonesia Rupiah, Philippines Peso and Thai Baht. If the U.S. interest rate hike is the major culprit, why does it affect Malaysia’s currency more than neighbours in the Southeast Asia over the last one month?

Malaysia is a net exporter of oil and the second largest producer of palm oil. Yet, despite crude oil prices remained above US$100 a barrel, the Ringgit plunged to its lowest level in 2 years. Worse, instead of appreciating against the greenback when the crude oil prices go up, as it usually did previously, the local currency seems to have diverged or broke away from the crude oil trend in recent months.

Embarrassingly, the Ringgit also traded lower against regional currencies. For the past month, it weakened against not only the mighty Singapore Dollar, but also Indonesia Rupiah and Thai Baht. It only performs better than the Philippines Peso. This could only mean one thing – Malaysia economy isn’t as rosy as the government was trumpeting, to put it mildly.

When the Federal Reserve increases the interest rate, the higher yields attract investment capital from investors abroad seeking higher returns on bonds or interest-rate products. Unless Malaysian Central Bank (Bank Negara) follows with a similar rate hike, investors will dump Ringgit in exchange for the “more valuable” US dollar, leading to plunging Ringgit.

Hilariously, the Bank Negara has said as recently as last month that it was still awaiting signs of a more sustained economic – suggesting that the economy was indeed struggling. If it increases interest rate, it will have a huge impact on deposit rates, lending rates as well as home loan interest rates. Meaning, without cheap money supply, local businesses and people with debts will be in trouble.

Following the Fed, Singapore banks have raised interest rates on mortgage loans. Bank Indonesia, whose benchmark interest rate is 3.5%, is expected to raise interest rates later this month. The Philippine central bank may consider rising its key interest rate in June. Obviously, Malaysia is under tremendous pressure to raise rate not only from the U.S., but also within the Southeast Asia.

True, raising interest rates would translate to higher mortgage payments while companies will have to pay higher financing costs, hurting the country’s economy, which is still trying to get back to pre-pandemic level. But not raising the interest rate would see more depreciation of Ringgit against the U.S. dollar (even against regional currencies), which may in turn lead to capital outflows.

Like it or not, the Malaysia’s central bank, which last raised its key policy rate in January 2018 by 0.25 percentage point to 3.25%, has to join the bandwagon. Without the rate hike, the Ringgit will most likely breach the 4.40 psychological levels. While a weak currency makes a nation’s export more competitive in global markets, it also means weak purchasing power.

Sure, Malaysia can subsidize fuel or petrol, but it doesn’t produce fertilizer or wheat or other raw materials, not to mention the labour shortage situation. All these need to be imported, triggering a rise in goods prices, hence the inflation. Therefore, weak currencies often result in inflation, if there isn’t already one, and could even worsen an existing inflation if the currency is weak.

Additionally, the Bank Negara’s 25 basis points compared to the Federal Reserve’s 50 basis points could be too little, if not too late. To add salt to injury, there was disturbing news that the prices of certain brands of cooking oil have gone up by as much as RM10 for a 5kg bottle, despite the fact Malaysia is the second largest producer of palm oil. The chain-reaction will definitely impact food inflation.

Unlike the U.S., inflation in Malaysia is caused by a weak currency more than by a surge in demands for products and services. Local consumers are not willing to pay more for products like a plate of economy rice or a bottle of cooking oil. They have no choice, but struggling to pay more largely due to the government’s failure to ensure Ringgit possesses a decent purchasing power.

No comments:

Post a Comment