Bridget Welsh

Published: Oct 26, 2024 12:02 PM

COMMENT | Recently, I was asked if there was one word to describe contemporary Malaysian politics, what would it be?

It’s not an easy question to answer. Malaysia’s politics has regularly been described through an ethnic (race/religion/region) lens, personalistic power, or corruption.

In recent times, there has been attention to broadening democracy and political instability, with an appreciation of a dynamic transformation occurring as a new generation of voters is speaking out and changing political narratives.

The negative coexists with many positives. It is hard to resist using multiple words for a complex, often messy, situation.

When pressed again, my one-word answer was “betrayal”. Allow me to explain.

Vignette 1: Reformasi, 1998-1999

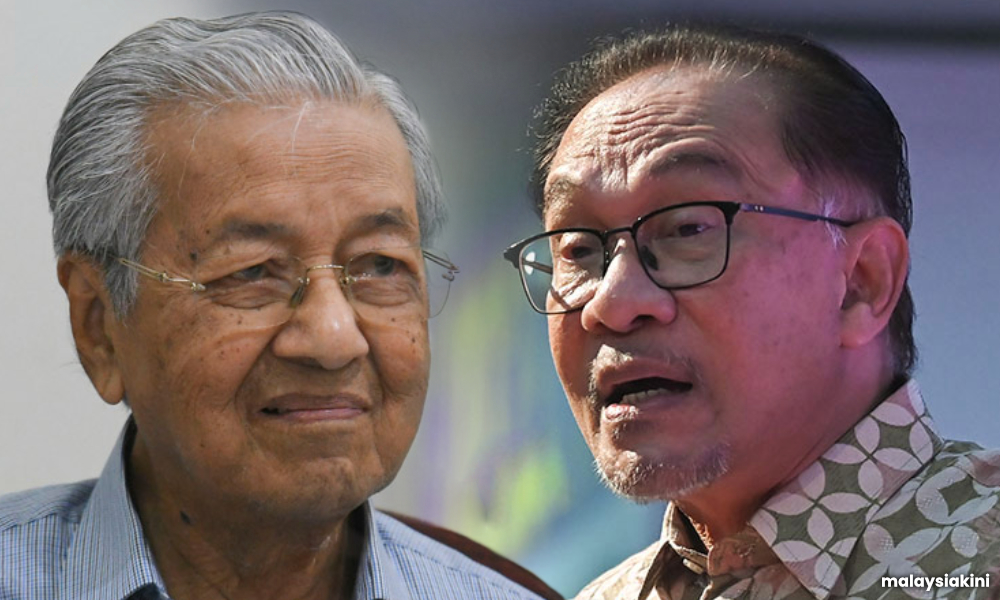

While books have been written about the mobilisation of Malaysians to push for democratic reforms, at its core, the reformasi movement started with a personal betrayal of two men - then-prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad and his then deputy, Anwar Ibrahim.

Published: Oct 26, 2024 12:02 PM

COMMENT | Recently, I was asked if there was one word to describe contemporary Malaysian politics, what would it be?

It’s not an easy question to answer. Malaysia’s politics has regularly been described through an ethnic (race/religion/region) lens, personalistic power, or corruption.

In recent times, there has been attention to broadening democracy and political instability, with an appreciation of a dynamic transformation occurring as a new generation of voters is speaking out and changing political narratives.

The negative coexists with many positives. It is hard to resist using multiple words for a complex, often messy, situation.

When pressed again, my one-word answer was “betrayal”. Allow me to explain.

Vignette 1: Reformasi, 1998-1999

While books have been written about the mobilisation of Malaysians to push for democratic reforms, at its core, the reformasi movement started with a personal betrayal of two men - then-prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad and his then deputy, Anwar Ibrahim.

Mahathir has never forgiven Anwar for challenging and attacking his family in 1998, and Anwar has similarly not forgotten the years of hardship he and his family endured as he was beaten, demonised and imprisoned in retaliation.

The antipathy continues with calls to the MACC office for asset declarations and regular quips, as personal antagonisms of distrust are deeply intertwined.

Out of personal betrayal, a mass movement was born for national politics.

Vignette 2: Najib and 1MDB, 2015-2014 (with damages paid by taxpayers for a lifetime)

There were similar personal betrayals around the multi-billion 1MDB scandal that came to light in 2015, as leaders within Umno challenged then-party president and prime minister Najib Abdul Razak and faced expulsion from the party for standing up against him.

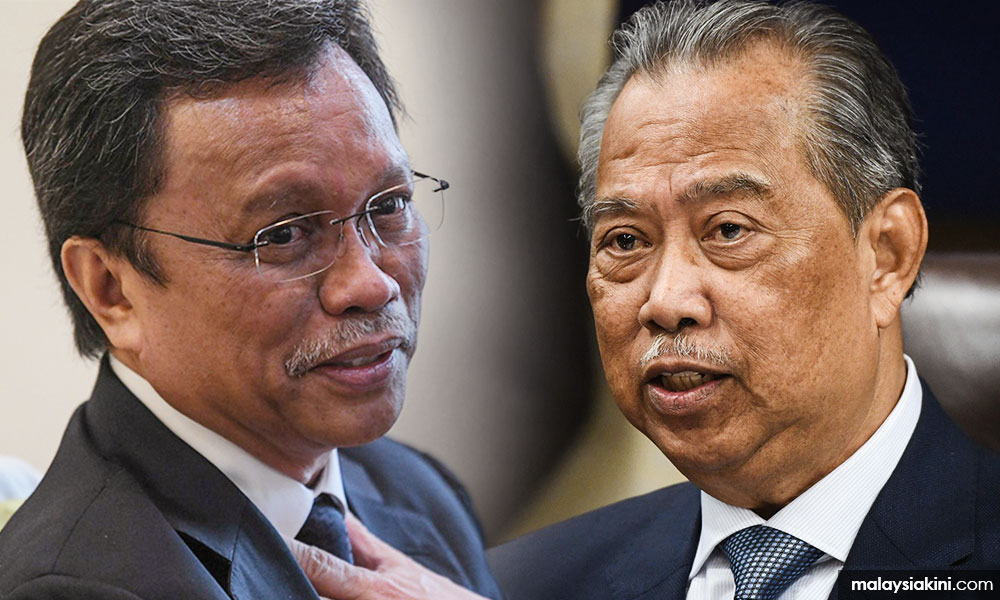

These men - Muhyiddin Yassin of Bersatu and Mohd Shafie Apdal with Warisan in Sabah - would play a key role in mobilising voters to oust Najib and elect a government that would charge the former PM for crimes associated with 1MDB in 2018.

Mohd Shafie Apdal (left) and Muhyiddin Yassin

Yet, the betrayal that stands out is a public one, of citizens’ trust broken over a scandal that remains the world’s largest case of kleptocracy in history, a scandal that would not have been possible without the former prime minister’s role in it.

Najib would pay the price by losing power and face conviction. Malaysian taxpayers continue to pay the price for the crimes involved and will do so for generations.

Less appreciated is Najib’s betrayal of his political base. Many continue to believe that the reason he lost power in 2018 was the 1MDB scandal.

This did play a role, especially in urban areas and among educated voters. Many of this group, however, did not vote for Najib in the first place.

My research on the 14th general election shows that the tipping group that shifted political power in 2018 was lower-class/income voters, Umno’s traditional core voters.

Najib’s governance that increased taxes on this community through the Goods and Service Tax (GST) and the rising cost of living stoked anger, as the party machinery of Umno weakened with a focus by elites on feeding themselves on the funds through corruption and patronage.

Yet, the betrayal that stands out is a public one, of citizens’ trust broken over a scandal that remains the world’s largest case of kleptocracy in history, a scandal that would not have been possible without the former prime minister’s role in it.

Najib would pay the price by losing power and face conviction. Malaysian taxpayers continue to pay the price for the crimes involved and will do so for generations.

Less appreciated is Najib’s betrayal of his political base. Many continue to believe that the reason he lost power in 2018 was the 1MDB scandal.

This did play a role, especially in urban areas and among educated voters. Many of this group, however, did not vote for Najib in the first place.

My research on the 14th general election shows that the tipping group that shifted political power in 2018 was lower-class/income voters, Umno’s traditional core voters.

Najib’s governance that increased taxes on this community through the Goods and Service Tax (GST) and the rising cost of living stoked anger, as the party machinery of Umno weakened with a focus by elites on feeding themselves on the funds through corruption and patronage.

The corruption around 1MDB only served to fuel personal greed within Umno. The party no longer protected the Malay grassroots, especially the most vulnerable. This sense of betrayal felt by Umno’s core traditional voters was decisive in Najib’s 2018 defeat.

Out of a mass betrayal through scandal and taking core voters for granted, the political movement of Umno was toppled.

Vignette 3: Sheraton Move, 2020

Two years later, personal antagonisms between Mahathir and Anwar would again prove decisive.

From the onset of Mahathir’s second tenure as prime minister in 2018, distrust fed divisions and undercut needed cooperation for governance.

Within two years, the Pakatan Harapan “Save Malaysia” coalition broke apart as leaders close to Anwar joined forces for power and positions, bringing back Umno and PAS to power as a result.

PAS and Bersatu leaders outside Istana Negara following the Sheraton Move on March 1, 2020

For many Malaysians - wrapped up in the emotions of hope and the promise of change after the country’s first political turnover of power in 2018 - this betrayal hit hard. Others saw this as vindication, as incumbents were returned to the government.

The betrayal brought in a period of unprecedented political instability and reshaped political alliances. It allowed new leaders to take over power, outside of the traditional political hierarchy, bringing new blood to leadership.

Vignette 4: Anwar’s Madani - 2023-2024

Now, only a few years later, Anwar is in power through elite deal-making. It is important to recognise that he and his coalition did not win a majority – a majority of voters for both Perikitan Nasional and Pakatan Harapan voted against corruption and Umno.

Anwar’s deal-making continues to reshape political alliances in his “unity” coalition, the Madani government, but it brought into power a leader shaped by his political relationships in and with Umno.

Those who wanted a different government from that of Umno now have the same party and practices in power, with Anwar providing the means for the party’s leaders and their family members to be rehabilitated, including through taxpayer-funded patronage.

Political charges are being granted a discharge not amounting to an acquittal (DNAA) and halved for political support for loyalty and political support as part of deals, as the groundwork for house arrest is clearly being prepared for those who merely express regret rather than genuine remorse or responsibility.

Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, who was granted a DNAA for his 47 corruption charges

As with Najib, the betrayal is a public one, an apparent abandonment of the principles of democratic reform and dismissal of the mandate of the voters.

Reformasi is seen to be ending at the hands of the person who used it to gain political power. Little meaningful changes have been made to address electoral reform, expand political rights, bolster the judiciary, improve race relations, curb corruption and check abuses of power and patronage.

Rather than strengthening political accountability, political institutions and building inclusion across groups in Malaysia, the focus remains on maintaining political power, to even include a personal mention of house arrest in a budget speech.

There appear to be few red lines that Anwar will not cross to hold onto power.

As with Najib, the betrayal is a public one, an apparent abandonment of the principles of democratic reform and dismissal of the mandate of the voters.

Reformasi is seen to be ending at the hands of the person who used it to gain political power. Little meaningful changes have been made to address electoral reform, expand political rights, bolster the judiciary, improve race relations, curb corruption and check abuses of power and patronage.

Rather than strengthening political accountability, political institutions and building inclusion across groups in Malaysia, the focus remains on maintaining political power, to even include a personal mention of house arrest in a budget speech.

There appear to be few red lines that Anwar will not cross to hold onto power.

Anwar’s parallels to Najib extend into his engagement with its political base. Anwar’s governance is effectively punishing the voters who voted for him, especially middle-class voters in urban areas, non-Malays and Indian voters.

The “attack the rich” Budget 2025 targeting the nonsensical notion of Top 15, a concept that does not account for the spending needs of families, especially in urban areas, is feeding discontent and feelings of betrayal.

This group pays 80 percent of Malaysian income taxes, funding infrastructure and increased salaries/bonuses of civil servants that Anwar continues to try (rather unsuccessfully) to win over.

Negative sentiments will only worsen when those paying income taxes are further demonised in everyday interactions at the petrol station in a (so-far) poorly administered subsidy removal process.

There are better ways to increase revenue fairly and less divisively. Taxes on the rich should focus on the super-wealthy, the top one percent and those who have taken advantage of patronage. Those who owe outstanding taxes should not be given clemency or political positions.

Concerns extend beyond the budget to governance. If there is any significant difference in the Madani government, it is that Anwar has brought with him the Islamisation he branded Umno with from the 1980s.

Minority concerns are being dismissed despite this group overwhelmingly voting for Harapan.

Betrayal repeats itself

Malaysian political history shows that alienating your political base comes with political peril.

Betrayal in Malaysian politics has historically come back to haunt those who engage in it, both personally and politically.

It remains unclear what this current period of betrayal will bring - internal defections, a strengthening of rehabilitated political opponents and new political alignments have happened in the past.

Ambitions and antagonisms at the elite level persist, as does distrust. The shadow of betrayal is ever present.

For now, a betrayal sentiment among the public has been evident in greater political disengagement and ambivalence, with fewer people voting especially.

As in 2018, one should not underestimate the politics of quiet disappointment and frustration.

It also remains to be seen if the inevitable closure of the Anwar and Mahathir era will make betrayal less of a decisive political force. Sadly, patterns are often learned and repeated.

For now, however, betrayal remains an overriding factor shaping national politics, in which Malaysia’s governing political elites are riding high, and more voters increasingly feel they are being taken for a ride.

BRIDGET WELSH is an honourary research associate of the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute, a senior research associate at Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, and a senior associate fellow at The Habibie Centre. Her writings can be found at bridgetwelsh.com

Betrayal No. 4 Anwar’s Madani - 2023-2024 has been deeply personal for me, as I had been a Reformasi supporter since 1998.

ReplyDeleteHis betrayal if the Reform Agenda has been deeply painful.

I never peronally felt betrayed by Mahathir and Najib, as I had always been clear that both are Very Bad Hombres, and the severe damage they did to Malaysia were very much predictable.