India and China: A strategic rapprochement shaped by US tariffs — Phar Kim Beng and Luthfy Hamzah

Monday, 18 Aug 2025 5:30 PM MYT

AUGUST 18 — When Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi arrived in New Delhi ahead of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s planned visit to China, the world paid attention.

The meeting was not merely another diplomatic formality, but a possible watershed in Asian geopolitics.

Against the backdrop of troops facing each other across the icy expanse of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and the heavy burden of US tariffs weighing on both economies, India and China are testing the waters of a strategic rapprochement. Their cautious recalibration of relations is not rooted in sentiment, but in necessity — especially in the face of mounting American pressure.

At the centre of this delicate dance lies the persistent military standoff in eastern Ladakh.

Nearly 60,000 troops remain deployed on both sides, a constant reminder of the fragility of the border and the tensions that erupted so violently in 2020.

Yet, Wang Yi’s talks with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and National Security Advisor Ajit Doval were not limited to the security domain.

They were also about advancing confidence-building measures (CBMs), the language of pragmatism when hard compromises are out of reach.

Reducing risks of accidental escalation and reintroducing predictability at the border are modest steps, but they set the stage for broader engagement.

Equally significant are the economic signals that followed. For the first time in five years, India and China are preparing to reopen historic Himalayan trade routes through Lipulekh, Shipki La, and Nathu La.

These mountain corridors, long dormant, symbolise more than commerce; they carry with them the potential to rebuild a lattice of interdependence.

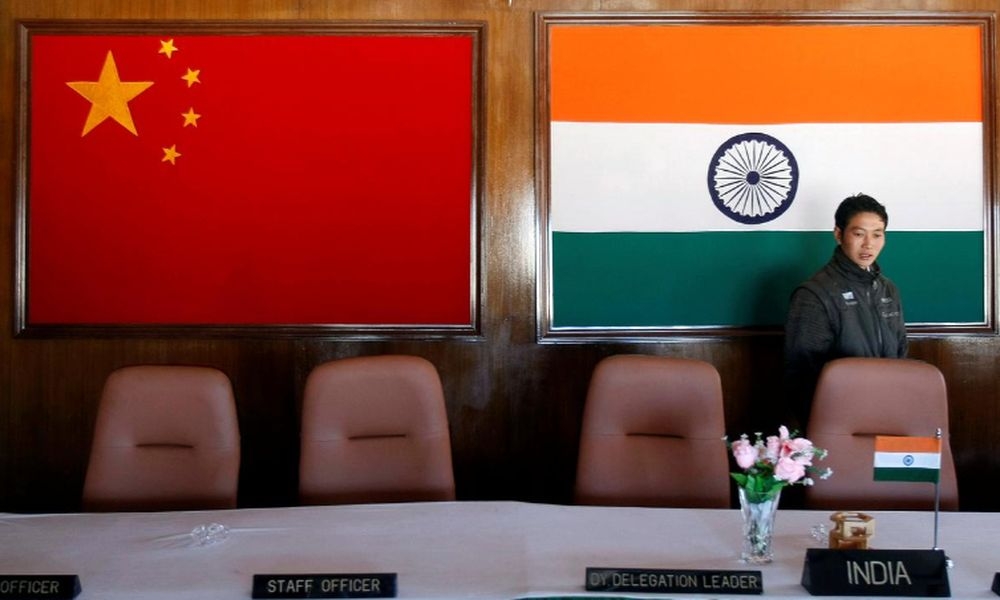

The writers argue that US tariffs have pushed India and China toward a pragmatic rapprochement, reopening trade routes and flights while cautiously managing border tensions. — Reuters pic

By reviving these links, both governments are acknowledging that estrangement is costly in an era of volatile supply chains and global tariff wars.

At a time when Washington is weaponising tariffs as high as 50 per cent, India and China appear determined to restore their own channels of exchange.

People-to-people ties are also inching forward. Both countries have asked their airlines to be ready to resume direct flights, a move that would mark a decisive gesture of normalisation.

Air connectivity between India and China has been absent for years, reflecting the diplomatic freeze of the post-Galwan era.

Restoring flights will not erase mistrust overnight, but it will inject momentum into academic exchanges, business partnerships, and tourism — soft but indispensable elements of reconciliation.

None of these moves should be seen in isolation. They are part of a broader recalibration driven by US policy.

Washington’s escalating tariffs under President Donald Trump’s second term have hardened fault lines across the global economy.

Ostensibly aimed at disciplining China, they have in practice complicated India’s own trade with the United States (US).

Instead of isolating Beijing, these tariffs have had the unintended effect of nudging Delhi and Beijing toward cautious alignment.

Strengthening solidarity among the Brics economies has become one visible consequence, as members seek to counterbalance of the acute pressures of American economic coercion.

For India, finding common cause with China — however tentatively — offers a way to manage exposure to Washington’s volatility.

This does not mean India is drifting wholesale into China’s orbit.

The mistrust born of historical rivalry, unresolved border disputes, and concerns over Beijing’s partnership with Islamabad runs deep.

Nor will Delhi forsake its strategic equities with Washington, Tokyo, and Canberra in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. Known widely as the Quad.

Rather, India’s pursuit of a rapprochement with China should be understood as a strategy of preventing itself by being pressured by Trump, especially his onerous tariff regime.

By reopening trade routes, restoring flights, and discussing CBMs, India is signalling that it will not allow its future to be dictated by a zero-sum rivalry between Washington and Beijing.

In this sense, the thaw between India and China is less about reconciliation and more about resilience.

It reflects a desire to assert autonomy in a multipolar world, to resist being boxed into binary choices.

For Beijing, easing tensions with India reduces the risk of a two-front strategic squeeze, freeing resources to deal with the United States in the Pacific.

For Delhi, balancing relations with China provides a counterweight to American unpredictability while preserving strategic flexibility. The convergence is pragmatic, not ideological.

What emerges from Wang Yi’s visit is the prospect of an incremental but important shift.

The reopening of mountain passes, the resumption of flights, and the easing of military tensions along the LAC all point to a relationship that may be moving from confrontation to coexistence.

The United States, in seeking to discipline China through tariffs, may ironically have created the very conditions for a Sino-Indian rapprochement.

The story is far from finished. Suspicion remains entrenched, and the road to genuine trust will be long.

Yet geopolitics has its moments of quiet inflection, when external pressure forces old rivals to rediscover common ground.

Wang Yi’s Delhi visit suggests that India and China, though wary, may now be prepared to walk that path together — not to embrace, but to avoid being entrapped by the reckless economics of others.

In the end, what binds them is not friendship but necessity, forged in the crucible of American tariffs and the shared desire to secure their place in an uncertain world order.

*Phar Kim Beng, PhD is professor of Asean Studies, International Islamic University of Malaysia and director of the Institute of Internationalisation and Asean Studies (IINTAS). Luthfy Hamzah is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Internationalisation and Asean Studies (IINTAS).

Rapprochement is supposed to be a good sign in international relationship between countries.

ReplyDeleteYet, this could NEVER work with 阿三哥. Past incidents & even the most recent SCO forum & the BRICS meeting have been torpedoed by the India's monkeying behaviorism, resulting in NO concrete agendas from these two organizations.

Now that India realizes it's out of favors with the US, politically & economically, he needs to look hard to grab some saving ropes for its political & economic relevancy in the current geopolitical configuration. India is looking for salvations from those member nations of SCO & BRICS.

Knowing those split-tongue behaviorism of India, it's a matter of time when it plays monkey again when the geopolitical tides turn to its ride.

Yindia and CCP are natural Frenemies.

ReplyDeletenatural Frenemies????!!!

DeleteThroughout the eons of history, China has NEVER ever launched a conquer yo overtake India. This is despite the fact that they share a common long border & in the know past, India was a place of fragmented small & feudalistic nations.

The hundred yrs of pommie colonization has incubated the onemanup attitude that now India behaves openly despite its insignificant power of nothing in the world stage.