Malaysia’s regressive citizenship amendments risk giving ‘Little Napoleons’ power to decide who gets to be a Malaysian, lawyer says

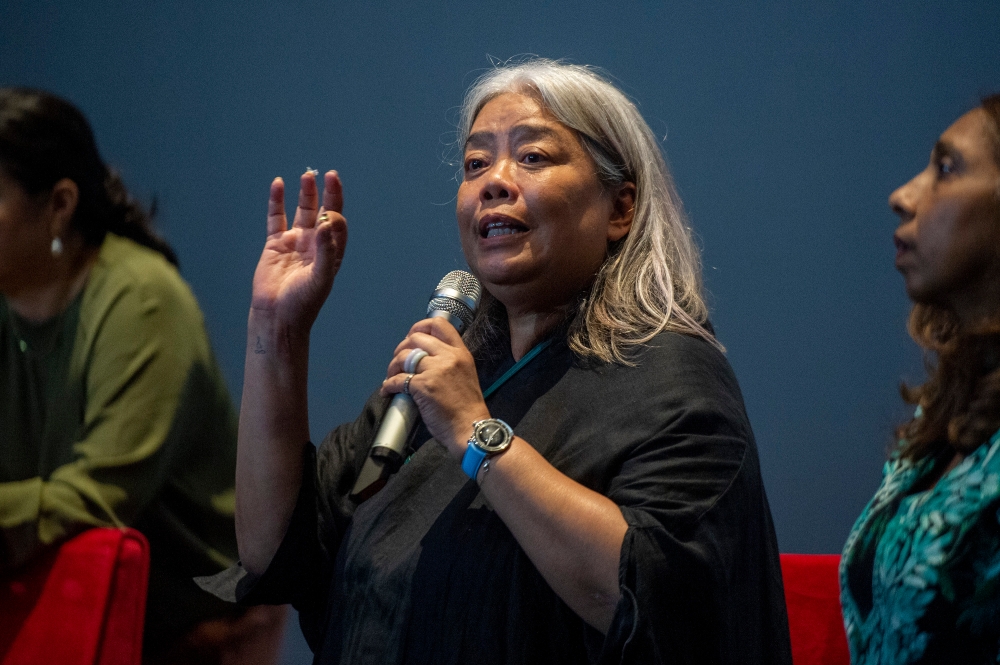

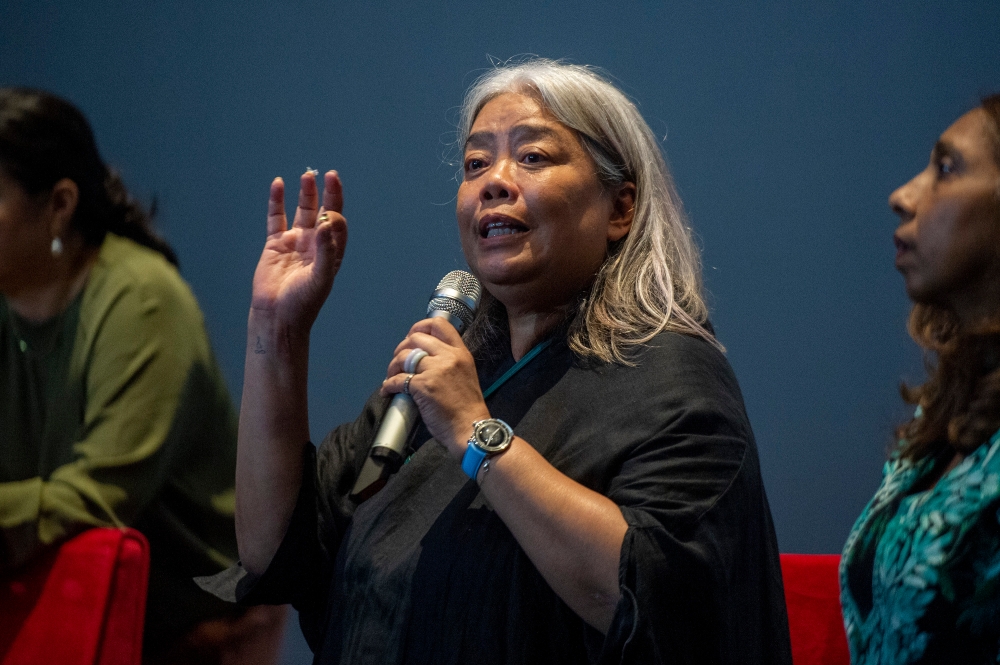

Voice of the Children chairman Sharmila Sekaran speaks during the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

Tuesday, 23 Jan 2024 7:00 AM MYT

KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 23 — The Malaysian government’s plans to bring “regressive” amendments to the country’s citizenship laws to Parliament means locally-born children would have their existing rights to automatically be citizens taken away, and will instead result in “Little Napoleons” having the power to decide if they should be registered as Malaysians, a lawyer has cautioned.

Sharmila Sekaran, who also chairs the child rights advocacy group Voice of the Children, said the planned regressive amendments to the Federal Constitution include a proposed move to change “citizenship by operation of law” to “citizenship by registration” for certain categories.

In other words, instead of being automatically eligible under the law to be a Malaysian when a child is born here and fulfils the citizenship conditions, the government will be the one deciding if the child should be registered as a Malaysian citizen.

“Which means a Little Napoleon sat in the Home Ministry gets to decide whether that child is going to be given citizenship, so it’s taken out of the hands of law, and put into the hands of unseen faces. Because we don’t know who these people are, who are approving or not approving,” she said as a panellist of a panel discussion over the weekend.

While the Federal Constitution puts the power in the hands of the home minister, Sharmila claims that the reality is that ministers follow the bidding of civil servants.

“And that is what we are really concerned about in terms of these proposed amendments, because no longer will children like ‘Abang’ and ‘Adik’ and a whole host of children like that be able to acquire citizenship automatically, when everything points to them being Malaysian and deserving of Malaysian citizenship,” she said, referring to two characters in the film Abang Adik who are stateless despite being born in Malaysia.

Sharmila was explaining the government’s plans to tack on regressive citizenship amendments and to bundle them together in one single package with a planned progressive constitutional amendment to enable Malaysian mothers to pass on their citizenship to their overseas-born children (just like Malaysian fathers are currently able to do).

Sharmila said the regressive amendments would make it even harder for stateless children to be recognised as citizens.

People attend the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

She also claimed the regressive amendments covered areas which the Home Ministry is unfamiliar with in terms of the realities on the ground, saying that the Home Ministry should then not attempt to make amendments — seen as regressive — to these citizenship provisions in the Federal Constitution without first carrying out further studies and work on gathering data on statelessness.

She also suggested that some of the regressive citizenship amendments are being “rushed through” to attempt to address the Sabah situation, specifically “Project IC” where individuals were allegedly given Malaysian citizenship in the 1990s to ensure they would vote for the government of the day, but said that these proposed amendments are unnecessary as the Malaysian government or Sabah itself can use alternative solutions.

“The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) has done a study which they released early last year detailing how Project IC happened, where the gaps were, what the issues were, that can be addressed separately through alternative measures.

“A lot of these issues can be addressed through procedural manner within the ministry through policies and standard operating procedures (SOPs), as well as coming up with a very sound statelessness determination procedure, which is what the Philippines and Indonesia have done, so you know, there are other measures,” she said.

“MA63 (The Malaysia Agreement 1963) has allowed both Sabah and Sarawak to reserve citizenship of the state and immigration into the state unto themselves, so Sabah and Sarawak can also utilise matters under MA63 to their benefit. So you know there are alternatives which we can come up with in terms of process and procedures without needing a constitutional amendment,” she said.

Suriani Kempe, president of Family Frontiers and the moderator of the panel discussion, said that the government can choose to split the progressive amendment for Malaysian mothers and the regressive amendments instead of putting them in a single Bill to be voted on in Parliament.

“So this idea that you have to vote on a harmful piece of legislation is actually a manufactured problem, this problem doesn’t have to be that way, there is a way out,” she said, saying that the government can proceed with the progressive amendment and further study the need for regressive amendments.

Suriani said the bundled amendments are akin to “trading rights” where the government would give Malaysian mothers their rights in exchange for taking away existing citizenship rights belonging to children, including abandoned babies born in Malaysia.

“And as president of Family Frontiers, I can say, even though we have been working for this amendment for the last 20 years for Malaysian mothers to have equal rights, we will not do it on the backs of vulnerable children, not in our name,” she said.

Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability Minister Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad speaks during the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability Minister Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, who was present at the panel discussion as a member of the audience, briefly responded to questions from the audience that were directed to him.

“I think they are very valid questions, but of course I mean, I’m part of the Cabinet, I have collective responsibility, all that I can say is that I have brought up — I mean, not just me — many members of the Cabinet, we have deliberated long and far on this matter with regards to the amendment. “We really wanted to realise the amendment with regards to the Family Frontiers case and we are also aware of the other issues that are being raised, but I can’t go further because I can’t speak for my Cabinet colleagues.

“But all that I can say is all these issues that have been brought up, I think for the one year since the minister has announced this matter, and we are trying our best to give the most progressive amendment as possible with regards to this matter because I think that is the desire of the government in principle,” he said.

Wong Kueng Hui, a former stateless child born in Malaysia to a Malaysian father and non-Malaysian mother and who only received his Malaysian identity card last year after 16 years of applying and fighting in the courts, had as a member of the audience asked three questions of Nik Nazmi, namely his views on the home minister’s proposed citizenship amendments and how it could be approved in the Cabinet and what are the federal government’s guarantees in carrying out reforms for stateless issues in Malaysia.

At the same panel discussion, panellist Yayasan Chow Kit co-founder Datuk Hartini Zainudin objected to the regressive amendments, stating: “If we allow the regressive amendments to go through, we will be the only country in the world that actually takes the rights of children away in the last 10 years. Just remember that — the only country in the world.”

Yayasan Chow Kit co-founder Datuk Hartini Zainudin speaks during the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

Hartini, who is also a child rights activist, explained the three different categories of vulnerable persons that are often confused together, namely refugees who usually have passports and are fleeing their country, migrants who also have passports who may be later undocumented such as when their visas expire or other issues related to their employers happen, and stateless persons.

Hartini zoomed in on stateless children, such as abandoned infants born in Malaysia whose parents are unknown and who have no legal identity and no documents, noting that such foundlings may have a chance of being issued a birth certificate if they are found by the Social Welfare Department (JKM) but would face difficulties even getting a birth certificate if they were found by non-governmental organisations or by kind strangers or good Samaritans.

She said even abandoned babies found by the JKM would have a hard time applying for Malaysian citizenship from the Home Ministry.

“The assumption that stateless persons are foreigners is a complete myth. Almost all the categories of childhood statelessness and foundlings are born in this country, they never left, there is no national security threat. Because when you say it’s a national security threat, the assumption is that they are outside the country coming in, they are not,” she said.

She said such stateless children who have no legal identity and without citizenship cannot go to school, cannot have access to healthcare services, and are unable to do things such as having a bank account and also cannot leave Malaysia.

“There is a deliberate narrative in this country to muddy the waters and say that migrants are the same as refugees, same as undocumented, same as stateless, they are all foreigners. They are not, please let us make that distinction.

“Stateless persons for all intents and purposes are within the country, they never left, they are born in this country and will die in this country, whether you choose to acknowledge them or try to wave a magic wand and make the numbers disappear, they are still here,” Hartini said.

(From right) Lawyers for Liberty director Zaid Malek, Buku Jalanan Chow Kit co-founder Siti Rahayu Baharin, Voice of the Children chairman Sharmila Sekaran, and Yayasan Chow Kit co-founder Datuk Hartini Zainudin during the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

Fellow panellist Lawyers for Liberty director Zaid Malek said bureaucratic hurdles make it difficult for people who are stateless to get Malaysian citizenship even though they are currently entitled to it under the law, such as with requirements to produce documents which they have no access to.

Some of these individuals may have received the wrong advice or sometimes give up on the whole process of being recognised as a Malaysian, and would remain stateless persons for decades from their childhood to their adulthood and would have “no future” without access to education and medical services, the lawyer said.

“So essentially statelessness is a problem with people who do not have citizenship of any other country, they do not have identifying documents from Malaysia or any other country. And what is important is because of the lack of documents, they don’t have any rights, on paper they are not a person, they are basically a ghost,” he said, adding that lacking documentation also brings the risk of exploitation and fear of being taken away by law enforcement officers.

Zaid said the proposed regressive amendments would take away the existing solutions to statelessness in the Federal Constitution, urging for the public to push their MPs to prevent these amendments from being passed in Parliament.

Fellow panellist Buku Jalanan Chow Kit co-founder Siti Rahayu Baharin highlighted the April 22, 1999 fatwa issued by the Muzakarah of the Fatwa Committee of the National Council for Islamic Affairs, where it stated that both babies and children found abandoned at any place in Malaysia are categorised as “anak jagaan negara” (ward of the state or coming under the government’s care) and will automatically be Muslims.

But Siti Rahayu said the regressive amendments — one which would include removing automatic citizenship recognition for abandoned babies and only allow citizenship by registration for them — would make such children become uncared for even though the fatwa had said they would be “anak jagaan negara”.

She stressed that these regressive amendments affect those who were born in Malaysia and who will grow up and die in the country and who only have this country and cannot go anywhere and who should be recognised as Malaysians, stressing that they are not refugees or foreigners.

Buku Jalanan Chow Kit co-founder Siti Rahayu Baharin speaks the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

The panel discussion with the four speakers from civil society was held after a screening on Sunday of the award-winning movie Abang Adik, which was organised by the United Nations' (UN) International Organisation for Migration together with the Malaysian Citizenship Rights Alliance (MCRA).

Prior to the panel discussion, the film's director Jin Ong attended a brief question-and-answer session with the audience.

The screening at the Golden Screen Cinemas (GSC) at The Starling Mall was attended by more than 300 persons, including representatives from the Australian High Commission, embassies of the Netherlands, Hungary, Singapore and Tajikistan, and the UN Resident Coordinator.

After the panel discussion, the MCRA launched its online petition titled “Malaysian MPs must reject Citizenship Amendments threatening vulnerable children” at the platform Change.org to oppose the regressive amendments.

At the time of writing, more than 790 individuals have signed in support of the petition addressed to Home Minister Datuk Seri Saifuddin Nasution Ismail, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim and MPs in the Dewan Rakyat.

The MCRA, which is formed of civil society groups, activists and impacted persons working on statelessness and citizenship rights, includes the organisations Family Frontiers; Yayasan Chow Kit; Buku Jalanan Chow Kit; Voice of Children; Stateless Malaysians Citizenship Movement; Little Yellow Flower Foundation and Development of Human Resources for Rural Areas (DHRRA) Malaysia.

Tuesday, 23 Jan 2024 7:00 AM MYT

KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 23 — The Malaysian government’s plans to bring “regressive” amendments to the country’s citizenship laws to Parliament means locally-born children would have their existing rights to automatically be citizens taken away, and will instead result in “Little Napoleons” having the power to decide if they should be registered as Malaysians, a lawyer has cautioned.

Sharmila Sekaran, who also chairs the child rights advocacy group Voice of the Children, said the planned regressive amendments to the Federal Constitution include a proposed move to change “citizenship by operation of law” to “citizenship by registration” for certain categories.

In other words, instead of being automatically eligible under the law to be a Malaysian when a child is born here and fulfils the citizenship conditions, the government will be the one deciding if the child should be registered as a Malaysian citizen.

“Which means a Little Napoleon sat in the Home Ministry gets to decide whether that child is going to be given citizenship, so it’s taken out of the hands of law, and put into the hands of unseen faces. Because we don’t know who these people are, who are approving or not approving,” she said as a panellist of a panel discussion over the weekend.

While the Federal Constitution puts the power in the hands of the home minister, Sharmila claims that the reality is that ministers follow the bidding of civil servants.

“And that is what we are really concerned about in terms of these proposed amendments, because no longer will children like ‘Abang’ and ‘Adik’ and a whole host of children like that be able to acquire citizenship automatically, when everything points to them being Malaysian and deserving of Malaysian citizenship,” she said, referring to two characters in the film Abang Adik who are stateless despite being born in Malaysia.

Sharmila was explaining the government’s plans to tack on regressive citizenship amendments and to bundle them together in one single package with a planned progressive constitutional amendment to enable Malaysian mothers to pass on their citizenship to their overseas-born children (just like Malaysian fathers are currently able to do).

Sharmila said the regressive amendments would make it even harder for stateless children to be recognised as citizens.

People attend the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

She also claimed the regressive amendments covered areas which the Home Ministry is unfamiliar with in terms of the realities on the ground, saying that the Home Ministry should then not attempt to make amendments — seen as regressive — to these citizenship provisions in the Federal Constitution without first carrying out further studies and work on gathering data on statelessness.

She also suggested that some of the regressive citizenship amendments are being “rushed through” to attempt to address the Sabah situation, specifically “Project IC” where individuals were allegedly given Malaysian citizenship in the 1990s to ensure they would vote for the government of the day, but said that these proposed amendments are unnecessary as the Malaysian government or Sabah itself can use alternative solutions.

“The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) has done a study which they released early last year detailing how Project IC happened, where the gaps were, what the issues were, that can be addressed separately through alternative measures.

“A lot of these issues can be addressed through procedural manner within the ministry through policies and standard operating procedures (SOPs), as well as coming up with a very sound statelessness determination procedure, which is what the Philippines and Indonesia have done, so you know, there are other measures,” she said.

“MA63 (The Malaysia Agreement 1963) has allowed both Sabah and Sarawak to reserve citizenship of the state and immigration into the state unto themselves, so Sabah and Sarawak can also utilise matters under MA63 to their benefit. So you know there are alternatives which we can come up with in terms of process and procedures without needing a constitutional amendment,” she said.

Suriani Kempe, president of Family Frontiers and the moderator of the panel discussion, said that the government can choose to split the progressive amendment for Malaysian mothers and the regressive amendments instead of putting them in a single Bill to be voted on in Parliament.

“So this idea that you have to vote on a harmful piece of legislation is actually a manufactured problem, this problem doesn’t have to be that way, there is a way out,” she said, saying that the government can proceed with the progressive amendment and further study the need for regressive amendments.

Suriani said the bundled amendments are akin to “trading rights” where the government would give Malaysian mothers their rights in exchange for taking away existing citizenship rights belonging to children, including abandoned babies born in Malaysia.

“And as president of Family Frontiers, I can say, even though we have been working for this amendment for the last 20 years for Malaysian mothers to have equal rights, we will not do it on the backs of vulnerable children, not in our name,” she said.

Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability Minister Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad speaks during the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability Minister Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, who was present at the panel discussion as a member of the audience, briefly responded to questions from the audience that were directed to him.

“I think they are very valid questions, but of course I mean, I’m part of the Cabinet, I have collective responsibility, all that I can say is that I have brought up — I mean, not just me — many members of the Cabinet, we have deliberated long and far on this matter with regards to the amendment. “We really wanted to realise the amendment with regards to the Family Frontiers case and we are also aware of the other issues that are being raised, but I can’t go further because I can’t speak for my Cabinet colleagues.

“But all that I can say is all these issues that have been brought up, I think for the one year since the minister has announced this matter, and we are trying our best to give the most progressive amendment as possible with regards to this matter because I think that is the desire of the government in principle,” he said.

Wong Kueng Hui, a former stateless child born in Malaysia to a Malaysian father and non-Malaysian mother and who only received his Malaysian identity card last year after 16 years of applying and fighting in the courts, had as a member of the audience asked three questions of Nik Nazmi, namely his views on the home minister’s proposed citizenship amendments and how it could be approved in the Cabinet and what are the federal government’s guarantees in carrying out reforms for stateless issues in Malaysia.

At the same panel discussion, panellist Yayasan Chow Kit co-founder Datuk Hartini Zainudin objected to the regressive amendments, stating: “If we allow the regressive amendments to go through, we will be the only country in the world that actually takes the rights of children away in the last 10 years. Just remember that — the only country in the world.”

Yayasan Chow Kit co-founder Datuk Hartini Zainudin speaks during the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

Hartini, who is also a child rights activist, explained the three different categories of vulnerable persons that are often confused together, namely refugees who usually have passports and are fleeing their country, migrants who also have passports who may be later undocumented such as when their visas expire or other issues related to their employers happen, and stateless persons.

Hartini zoomed in on stateless children, such as abandoned infants born in Malaysia whose parents are unknown and who have no legal identity and no documents, noting that such foundlings may have a chance of being issued a birth certificate if they are found by the Social Welfare Department (JKM) but would face difficulties even getting a birth certificate if they were found by non-governmental organisations or by kind strangers or good Samaritans.

She said even abandoned babies found by the JKM would have a hard time applying for Malaysian citizenship from the Home Ministry.

“The assumption that stateless persons are foreigners is a complete myth. Almost all the categories of childhood statelessness and foundlings are born in this country, they never left, there is no national security threat. Because when you say it’s a national security threat, the assumption is that they are outside the country coming in, they are not,” she said.

She said such stateless children who have no legal identity and without citizenship cannot go to school, cannot have access to healthcare services, and are unable to do things such as having a bank account and also cannot leave Malaysia.

“There is a deliberate narrative in this country to muddy the waters and say that migrants are the same as refugees, same as undocumented, same as stateless, they are all foreigners. They are not, please let us make that distinction.

“Stateless persons for all intents and purposes are within the country, they never left, they are born in this country and will die in this country, whether you choose to acknowledge them or try to wave a magic wand and make the numbers disappear, they are still here,” Hartini said.

(From right) Lawyers for Liberty director Zaid Malek, Buku Jalanan Chow Kit co-founder Siti Rahayu Baharin, Voice of the Children chairman Sharmila Sekaran, and Yayasan Chow Kit co-founder Datuk Hartini Zainudin during the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

Fellow panellist Lawyers for Liberty director Zaid Malek said bureaucratic hurdles make it difficult for people who are stateless to get Malaysian citizenship even though they are currently entitled to it under the law, such as with requirements to produce documents which they have no access to.

Some of these individuals may have received the wrong advice or sometimes give up on the whole process of being recognised as a Malaysian, and would remain stateless persons for decades from their childhood to their adulthood and would have “no future” without access to education and medical services, the lawyer said.

“So essentially statelessness is a problem with people who do not have citizenship of any other country, they do not have identifying documents from Malaysia or any other country. And what is important is because of the lack of documents, they don’t have any rights, on paper they are not a person, they are basically a ghost,” he said, adding that lacking documentation also brings the risk of exploitation and fear of being taken away by law enforcement officers.

Zaid said the proposed regressive amendments would take away the existing solutions to statelessness in the Federal Constitution, urging for the public to push their MPs to prevent these amendments from being passed in Parliament.

Fellow panellist Buku Jalanan Chow Kit co-founder Siti Rahayu Baharin highlighted the April 22, 1999 fatwa issued by the Muzakarah of the Fatwa Committee of the National Council for Islamic Affairs, where it stated that both babies and children found abandoned at any place in Malaysia are categorised as “anak jagaan negara” (ward of the state or coming under the government’s care) and will automatically be Muslims.

But Siti Rahayu said the regressive amendments — one which would include removing automatic citizenship recognition for abandoned babies and only allow citizenship by registration for them — would make such children become uncared for even though the fatwa had said they would be “anak jagaan negara”.

She stressed that these regressive amendments affect those who were born in Malaysia and who will grow up and die in the country and who only have this country and cannot go anywhere and who should be recognised as Malaysians, stressing that they are not refugees or foreigners.

Buku Jalanan Chow Kit co-founder Siti Rahayu Baharin speaks the special screening of ‘Abang Adik’ film at Starling Mall, Petaling Jaya January 21, 2024. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

The panel discussion with the four speakers from civil society was held after a screening on Sunday of the award-winning movie Abang Adik, which was organised by the United Nations' (UN) International Organisation for Migration together with the Malaysian Citizenship Rights Alliance (MCRA).

Prior to the panel discussion, the film's director Jin Ong attended a brief question-and-answer session with the audience.

The screening at the Golden Screen Cinemas (GSC) at The Starling Mall was attended by more than 300 persons, including representatives from the Australian High Commission, embassies of the Netherlands, Hungary, Singapore and Tajikistan, and the UN Resident Coordinator.

After the panel discussion, the MCRA launched its online petition titled “Malaysian MPs must reject Citizenship Amendments threatening vulnerable children” at the platform Change.org to oppose the regressive amendments.

At the time of writing, more than 790 individuals have signed in support of the petition addressed to Home Minister Datuk Seri Saifuddin Nasution Ismail, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim and MPs in the Dewan Rakyat.

The MCRA, which is formed of civil society groups, activists and impacted persons working on statelessness and citizenship rights, includes the organisations Family Frontiers; Yayasan Chow Kit; Buku Jalanan Chow Kit; Voice of Children; Stateless Malaysians Citizenship Movement; Little Yellow Flower Foundation and Development of Human Resources for Rural Areas (DHRRA) Malaysia.

No comments:

Post a Comment