Break Bernas rice monopoly - Malaysians are fleeced

M. Krishnamoorthy

A media coach, associate professor and an undercover journalist

Image credit: The Edge

Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad gave the rice monopoly to Padiberas Nasional (Bernas) in 1996. Since then, rice prices have increased about five times, rice retailers complained.

On 5th December last year, PMX Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim revealed that he spoke to tycoon Tan Sri Syed Mokhtar Al-Bukhary about the latter’s perceived monopoly of rice import through national rice company Bernas.

He had “reprimanded” the billionaire but stopped short of revealing details of the purported conversation.

Anwar vowed to carry out his reform agenda fully and said among his top priorities would be to break existing monopolies over supply chains by politically connected elites.

Today, Malaysians ask if the rice price increase is a backlash as they suffer. PMX's action-oriented Minister will now pursue talks with India. Hopefully, the price will be stabilised.

Bernas is the sole rice importer for Malaysia, and its mandate is to ensure the stability of prices in the domestic rice market and food security in the country. Who is monitoring Bernas KPI? Are they meeting the KPIs? What are the penalties if they fail?

Can a Bernas in meeting Government KPIs result in removing Bernas’ monopoly?

Malaysians are asking why Malaysia suddenly has an extreme shortage of locally grown rice. It’s Bernas's role to ensure a steady supply of rice. Allegations by rice traders that Bernas artificially created the shortage of rice. Have the authorities looked into these allegations?

On the other hand, there is plenty of imported rice. Malaysia produces 1.6 million metric tons of rice annually and imports another 800,000 tons. A substantial amount of rice is imported from India.

Billionaire Syed Mokhtar Bukhari is the rice king who has been given a monopoly over all rice imports into the country and the purchase of all rice production from Malaysian farmers.

When India recently banned rice exports, Malaysia's imported rice suffered shortages. Instead, Malaysia's supply of locally grown rice disappeared from the shelves, but imported rice is fully available.

It was reported that local rice, which is price-controlled and cheaper, has long been repackaged and sold as more expensive imported rice. This is because local rice is of higher quality and can be sold as “imported rice” at higher prices.

To 'make up' the diminished number of price-controlled stocks, they have been importing lower quality, cheaper Indian rice and selling it as price-controlled, lower quality, “local rice”.

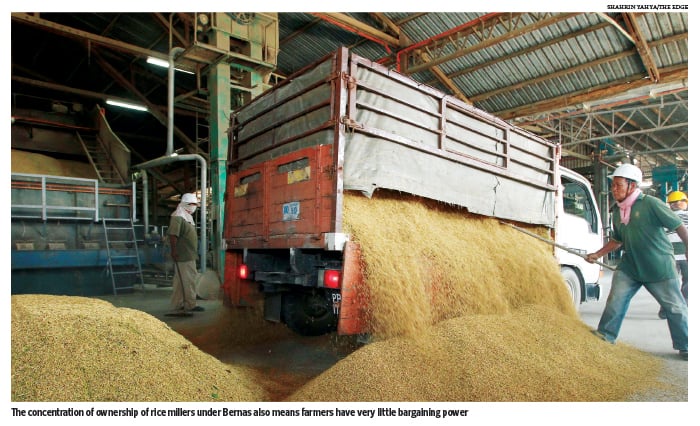

Local farmers have long complained that Bernas shortchanges them with low buying prices for their rice. They cannot sell their rice to anyone else. So Bernas buys their rice ex-farm at lower prices, repackages it, and sells it as imported rice at higher prices.

Hence, when India recently banned rice exports, “local rice” disappeared from Malaysian stores. Instead, “imported rice” is fully available.

These days, it can be challenging to buy a 10 kg bag of local white rice, better known as the Super Special Local (Tempatan) 5% rice (SST 5%), from the neighbourhood store or hypermarket.

There seems to be no clear answer to the root cause. The Government must get to the crux of it and implement its reforms to reduce rice prices.

Questions Malaysians are asking?

Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad gave the rice monopoly to Padiberas Nasional (Bernas) in 1996. Since then, rice prices have increased about five times, rice retailers complained.

On 5th December last year, PMX Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim revealed that he spoke to tycoon Tan Sri Syed Mokhtar Al-Bukhary about the latter’s perceived monopoly of rice import through national rice company Bernas.

He had “reprimanded” the billionaire but stopped short of revealing details of the purported conversation.

Anwar vowed to carry out his reform agenda fully and said among his top priorities would be to break existing monopolies over supply chains by politically connected elites.

Today, Malaysians ask if the rice price increase is a backlash as they suffer. PMX's action-oriented Minister will now pursue talks with India. Hopefully, the price will be stabilised.

Bernas is the sole rice importer for Malaysia, and its mandate is to ensure the stability of prices in the domestic rice market and food security in the country. Who is monitoring Bernas KPI? Are they meeting the KPIs? What are the penalties if they fail?

Can a Bernas in meeting Government KPIs result in removing Bernas’ monopoly?

Malaysians are asking why Malaysia suddenly has an extreme shortage of locally grown rice. It’s Bernas's role to ensure a steady supply of rice. Allegations by rice traders that Bernas artificially created the shortage of rice. Have the authorities looked into these allegations?

On the other hand, there is plenty of imported rice. Malaysia produces 1.6 million metric tons of rice annually and imports another 800,000 tons. A substantial amount of rice is imported from India.

Billionaire Syed Mokhtar Bukhari is the rice king who has been given a monopoly over all rice imports into the country and the purchase of all rice production from Malaysian farmers.

When India recently banned rice exports, Malaysia's imported rice suffered shortages. Instead, Malaysia's supply of locally grown rice disappeared from the shelves, but imported rice is fully available.

It was reported that local rice, which is price-controlled and cheaper, has long been repackaged and sold as more expensive imported rice. This is because local rice is of higher quality and can be sold as “imported rice” at higher prices.

To 'make up' the diminished number of price-controlled stocks, they have been importing lower quality, cheaper Indian rice and selling it as price-controlled, lower quality, “local rice”.

Local farmers have long complained that Bernas shortchanges them with low buying prices for their rice. They cannot sell their rice to anyone else. So Bernas buys their rice ex-farm at lower prices, repackages it, and sells it as imported rice at higher prices.

Hence, when India recently banned rice exports, “local rice” disappeared from Malaysian stores. Instead, “imported rice” is fully available.

These days, it can be challenging to buy a 10 kg bag of local white rice, better known as the Super Special Local (Tempatan) 5% rice (SST 5%), from the neighbourhood store or hypermarket.

There seems to be no clear answer to the root cause. The Government must get to the crux of it and implement its reforms to reduce rice prices.

Questions Malaysians are asking?

- Is there hoarding happening at the levels of wholesalers or millers?

- Is repackaging of quality local rice at higher prices (more profits) taking place?

- Is it because of Bernas monopoly that it announced in September (2023) the increase in the price of rice by 36%, from RM2,350 to RM3,200?

- What is the criteria for the increase?

- Has the rice price increased because of India’s rice export ban?

- Can the Government work towards bringing down the rice price?

Freelance Writer M. Krishnamoorthy (www.imkrishna.net) is a media coach, associate professor and undercover journalist. He has freelanced with Bernama, NST, The Star, and Malaysiakini. He also freelances as a fixer/coordinator for CNN, BBC, German and Australian Television networks and the New York Times. As an undercover journalist, he has highlighted society's concerns going undercover as a beggar, security guard, blind man, disabled salesman and Member of Parliament.

No comments:

Post a Comment