Book review: former diplomat’s fascinating synthesis of Dr Mahathir – P. Gunasegaram

Datuk Dennis Ignatius writes an illuminating, absorbing, engrossing account of ex-PM in Paradise Lost: Mahathir and the End of Hope

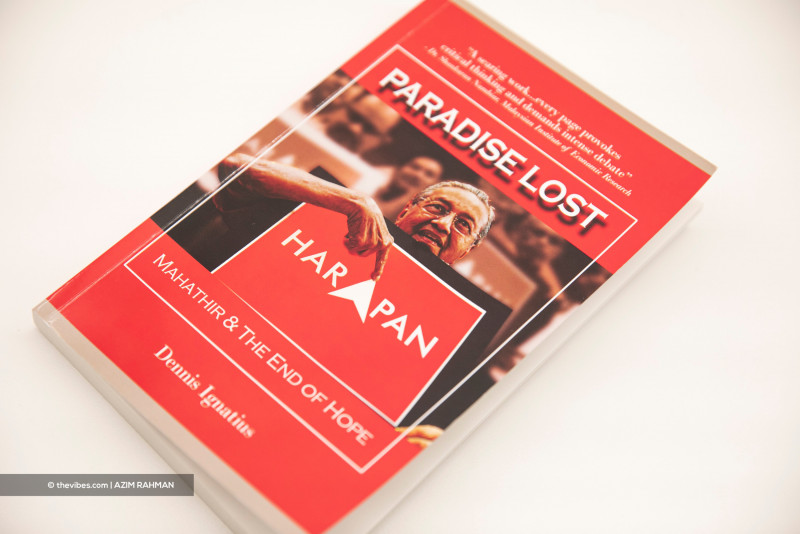

Ex-prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad is a familiar subject for author Datuk Dennis Ignatius, who goes on to dissect and discuss some of the politician’s various actions. – AZIM RAHMAN/The Vibes pic, September 23, 2021

FORMER ambassador Datuk Dennis Ignatius, who is now enjoying a new life as a writer and columnist, has made an important contribution to the volume of literature on former prime minister two times over Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, especially on his more recent misadventures.

Most books on Dr Mahathir have been either written by the man himself, who is a prolific author from the times of his The Malay Dilemma over 50 years ago, or are fawning adulations of him no doubt written by paid pens to paint an overly rosy picture of him. Therefore, there are probably fewer than a handful of books that make a meaningful contribution to a rational and argued discussion of Dr Mahathir.

Ignatius knows Dr Mahathir well from his days as envoy in different countries and capacities, and had high respect and regard for him previously. His is the only recent book I know of that has cogently and convincingly criticised his various actions, attempting to synthesise a whole picture of him and to understand what drives him as a person.

He confesses: “I was an unabashed supporter of Pakatan Harapan… I used my pen in support of Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, PH and Malaysia Baru.” He was not alone – millions of Malaysians embraced Dr Mahathir’s second coming despite years of tyranny and misrule under him, believing him to be a repentant, changed man who now wanted to do good.

Dr Mahathir milked this to the hilt – ahead of the 14th general election, a video was circulated widely and went viral, showing him talking to a girl. A teary-eyed Dr Mahathir was telling her that there was much he had to put right, and he had little time to do so.

The author’s disappointment in him was obvious, and he explains why.

Dr Mahathir saved our democracy only to do it irreparable harm… He didn’t even try; instead, he went back to being the Dr Mahathir of old. He played his racist games; he gave new life to his racist ideology. He reneged on his promises and undermined his coalition in pursuit of Malay supremacy. He, more than anyone else, must be held responsible.”

Ignatius believes that the many dissenting voices in Malaysia are opening up the public space to “discussions about our future”, something that should have been done a long time ago. He states his purpose this way: “This book is my contribution to that cause, an attempt to challenge Dr Mahathir’s vision for the nation, and to suggest that it is both inconsistent with the Merdeka compact and utterly ruinous of our future.”

He writes from his position as a columnist and contemporary commentator who had inside knowledge of what happened within the government and how the civil service changed over the years. This is where there is value in this work – it’s a living, moving, changing, contemporary document, not a dry, academic, impersonal look, but the supported opinions of one who is Malaysian and cares deeply and passionately for the welfare of the country.

It is the most important work on Dr Mahathir that has been written since two of the most seminal works on him that I have read, one by an academic and the other by a veteran journalist, both of which were rather interesting and gave new insights into the man who has most shaped Malaysia – for better and/or worse.

The first is a book published in 1995 by scholar Khoo Boo Teik titled the Paradoxes of Mahathirism: An Intellectual Biography of Mahathir Mohamad covering some 14 of his 22 years as prime minister from 1981 to 2003.

The second book, published in 2003, is titled Malaysian Maverick: Mahathir Mohamad in Turbulent Times and was written by the late veteran Australian journalist Barry Wain, who worked for many years with the Asian Wall Street Journal, where he covered Malaysia extensively.

Khoo, who reviewed Wain’s book, had this to say: “All that poses a huge riddle – how much was Dr Mahathir the master of situations and the manipulator of puppets; to what extent was he an instrument of social and political forces stronger than his own agency?

“Wain does not address this riddle, which no academic or journalist writing on Dr Mahathir has been able to answer fully. But Wain’s updated information provides some basis for tentative replies.”

Ignatius’ book bridges some of these gaps. It’s the only substantive piece of work on Dr Mahathir I have seen that covers the period from 2009 up to the present time, and dips back in time occasionally to try and explain the paradox that Dr Mahathir clearly is, with the focus being the present and the future.

Datuk Dennis Ignatius covers a mosaic of developments in Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s (pic) animosity towards Datuk Seri Najib Razak and Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, detailing how his actions have shaped the country for decades. – AFP pic, September 23, 2021

It is written in an easy, conversational, journalistic style with little of the “on-the-one-hand-and-on-the-other-hand” approach favoured by many academics. As befits a political commentator, the opinions are frank, even brutal, pulling no punches, but always with sufficient justification for the views.

The book is split into three parts – politics, race and religion, and reform. I would have liked to see an entire separate section on the corruption that Dr Mahathir helped nurture and expand during his first – and even his second – term. Instead, that is part of the section on reform, though an important one.

The first chapters of the political section begin with a very short history of the colossus that Dr Mahathir was in Malaysia’s history and his impact (mostly adverse) on the nation. It moves on quickly to detail his return in the 2018 elections as prime minister yet again.

Ignatius pieces together a mosaic of developments in Dr Mahathir’s animosity towards Datuk Seri Najib Razak. In this riveting tale of first getting rid of Najib and then stopping Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim from getting the top position, etc, one learns lots of the many facets of intertwined factors shaping the destiny of the country.

Dr Mahathir feigned surprise over DAP, at first saying they were not at all Chinese like MCA, but multiracial, as if it took him that long to find out. And when the gloves came off later, he again demonised DAP. On Anwar, Ignatius says: “That Dr Mahathir was prepared to go to such lengths to destroy Anwar was a measure of how ruthless and vindictive he could be towards his enemies.”

The book deals with Malay angst and the replaying of the race card, beginning with the demonisation of DAP again and the failure of PH itself to address these issues, largely because of Dr Mahathir himself, who seemed to downplay the PH construct. Dr Mahathir, despite coming to power with non-Malay support, decried the reliance on non-Malays to share power.

Ignatius goes on to question the motive of such arguments by Dr Mahathir. “Why make such appointments and then grumble about having to make concessions for non-Malays? Was it part of his strategy to play the race card to isolate DAP and Anwar, whom he had already cast as insufficiently committed to the Malay agenda?”

Those questions may have been considered heretical at one point in time. No longer. They are valid and must be asked. The consequences were serious, and at the end of the day, that strategy cost Dr Mahathir dearly, allowing a beaten Umno to claw back into the fray.

Ignatius allots three reasons for Dr Mahathir’s behaviour – his visceral hatred for Anwar, his resentment at DAP and PKR for staying in power, and his desire to have his own way. It’s the way he builds his case that is impressive, supporting his assertions by citing numerous reports and extracts. But he does it in a way that does not intrude into your reading pleasure and continuity.

In the second-last chapter in the section on politics, he makes an evocative plea for multiculturalism and democracy, which ends thus: “….if both multiculturalism and democracy have no future in Malaysia, what are we left with? If we are not all united by a common and equal citizenship, we are nothing more than disparate tribal groups, victims of a common history trapped within the confines of a common geography. And if it’s not a secular constitutional democracy, what are we left with other than a hideous apartheid pseudo-religious fascist kleptopia?”

There are gems like that interspersed throughout the book, distilled nuggets of wisdom and wit from a generation of diplomacy, an acute awareness of the things that drive society and the peculiar problems of politics in Malaysia, and keeping up assiduously with the latest developments in the nation.

Another example, on restoring Malay hegemony: “Dr Mahathir was right when he suggested that the Malays had become enslaved, but it was not enslavement to other communities, but to bigotry and fear. All he and other Malay supremacists have done is undermine the faith and confidence of the Malays in themselves. It may have served Dr Mahathir’s political agenda, but it has left the Malays distracted and constantly looking over their shoulders for an enemy that simply isn’t there. And, of course, he has deprived us all of the space we needed to learn to accommodate each other and cohere as a nation.”

In the next section, Ignatius deals with the problem of race, starting with Dr Mahathir’s pathological fear of the Malays being inundated by the Chinese flood if the special privileges of the Malays were removed, moving on to concepts of the social contract, an unwritten document without basis pushed by Malay ultras to maintain Malay political dominance and supremacy.

It is written in an easy, conversational, journalistic style with little of the “on-the-one-hand-and-on-the-other-hand” approach favoured by many academics. As befits a political commentator, the opinions are frank, even brutal, pulling no punches, but always with sufficient justification for the views.

The book is split into three parts – politics, race and religion, and reform. I would have liked to see an entire separate section on the corruption that Dr Mahathir helped nurture and expand during his first – and even his second – term. Instead, that is part of the section on reform, though an important one.

The first chapters of the political section begin with a very short history of the colossus that Dr Mahathir was in Malaysia’s history and his impact (mostly adverse) on the nation. It moves on quickly to detail his return in the 2018 elections as prime minister yet again.

Ignatius pieces together a mosaic of developments in Dr Mahathir’s animosity towards Datuk Seri Najib Razak. In this riveting tale of first getting rid of Najib and then stopping Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim from getting the top position, etc, one learns lots of the many facets of intertwined factors shaping the destiny of the country.

Dr Mahathir feigned surprise over DAP, at first saying they were not at all Chinese like MCA, but multiracial, as if it took him that long to find out. And when the gloves came off later, he again demonised DAP. On Anwar, Ignatius says: “That Dr Mahathir was prepared to go to such lengths to destroy Anwar was a measure of how ruthless and vindictive he could be towards his enemies.”

The book deals with Malay angst and the replaying of the race card, beginning with the demonisation of DAP again and the failure of PH itself to address these issues, largely because of Dr Mahathir himself, who seemed to downplay the PH construct. Dr Mahathir, despite coming to power with non-Malay support, decried the reliance on non-Malays to share power.

Ignatius goes on to question the motive of such arguments by Dr Mahathir. “Why make such appointments and then grumble about having to make concessions for non-Malays? Was it part of his strategy to play the race card to isolate DAP and Anwar, whom he had already cast as insufficiently committed to the Malay agenda?”

Those questions may have been considered heretical at one point in time. No longer. They are valid and must be asked. The consequences were serious, and at the end of the day, that strategy cost Dr Mahathir dearly, allowing a beaten Umno to claw back into the fray.

Ignatius allots three reasons for Dr Mahathir’s behaviour – his visceral hatred for Anwar, his resentment at DAP and PKR for staying in power, and his desire to have his own way. It’s the way he builds his case that is impressive, supporting his assertions by citing numerous reports and extracts. But he does it in a way that does not intrude into your reading pleasure and continuity.

In the second-last chapter in the section on politics, he makes an evocative plea for multiculturalism and democracy, which ends thus: “….if both multiculturalism and democracy have no future in Malaysia, what are we left with? If we are not all united by a common and equal citizenship, we are nothing more than disparate tribal groups, victims of a common history trapped within the confines of a common geography. And if it’s not a secular constitutional democracy, what are we left with other than a hideous apartheid pseudo-religious fascist kleptopia?”

There are gems like that interspersed throughout the book, distilled nuggets of wisdom and wit from a generation of diplomacy, an acute awareness of the things that drive society and the peculiar problems of politics in Malaysia, and keeping up assiduously with the latest developments in the nation.

Another example, on restoring Malay hegemony: “Dr Mahathir was right when he suggested that the Malays had become enslaved, but it was not enslavement to other communities, but to bigotry and fear. All he and other Malay supremacists have done is undermine the faith and confidence of the Malays in themselves. It may have served Dr Mahathir’s political agenda, but it has left the Malays distracted and constantly looking over their shoulders for an enemy that simply isn’t there. And, of course, he has deprived us all of the space we needed to learn to accommodate each other and cohere as a nation.”

In the next section, Ignatius deals with the problem of race, starting with Dr Mahathir’s pathological fear of the Malays being inundated by the Chinese flood if the special privileges of the Malays were removed, moving on to concepts of the social contract, an unwritten document without basis pushed by Malay ultras to maintain Malay political dominance and supremacy.

Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s (pic) unending lobbying for Malay supremacy is highlighted in Datuk Dennis Ignatius’ book. – The Vibes file pic, September 23, 2021

He discusses the concept of Bangsa Malaysia and Dr Mahathir’s convoluted reasons for why it was not achieved, the unsubstantiated narrative about the unpatriotic non-Malay and the increasing racial schism within a once multiracial civil service, which accelerated during Dr Mahathir’s time.

The rewriting of history to lessen the influence of those other than Malays in the history of Malaysia is another sore point. Ignatius delves into history to point out the contributions of figures besides those usually named to the development of Malaysia in his chapter, reclaiming history.

One of the key features of Malaysia is its undue Islamisation, with political leaders, including Dr Mahathir, claiming that Malaysia is an Islamic state, and even an Islamic fundamentalist state. He traces it to the Saudis for building up a cadre of Wahhabi-trained academics, preachers and teachers, now agitating for greater Islamisation.

Inevitably, the discussion moved on to an Islamic state and hudud law, but not before delving into some interesting details on how PAS president Datuk Seri Abdul Hadi Awang once praised DAP for standing with PAS when the Kelantan government fell to Barisan Nasional in 1978. His stance changed later.

It should be obvious that Hadi’s Islamic state is the complete antithesis of the democratic, secular and inclusive character of our constitution, and for that reason alone must be taken seriously…. He is by far the most bigoted and extremist politician in the country, the greatest danger to our way of life and indeed to our very existence as a secular constitutional democracy.”

The last section of the book deals with reform, or the lack of it, under Dr Mahathir’s prime ministership round two. Even here, as Ignatius points out with example after example, the issue of race and religion was used and whipped up again and again to prevent many key reforms. The term “deep state” comes up as an obstacle to reform.

He traces the economic origins of Malay hegemony and writes: “In any case, the NEP (New Economic Policy) was never purely about the eradication of poverty irrespective of race or forging national unity; it hid a more crucial and overarching political objective – ensuring Malay hegemony.”

How true! And because it was true, the enormous opportunities it created gave rise to corruption on a grand scale, leading to the largest theft in the world via 1Malaysia Development Bhd.

For all that talk of doom and gloom, Ignatius ends on a hopeful note. He quotes Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra al-Haj first: “We must be brave, we must be fair and we must be just, so that come what may, we shall be ready as united Malaysian people to meet it.”

And then he says: “Let us, therefore, not grow weary of fighting for what is good and just, for in due season we will reap, if we do not give up.”

It’s a broad canvas that Ignatius paints, and an ambitious undertaking. Perhaps, one of the book’s weaknesses is that the sweep is a panorama too wide, with details getting lost in the size. Ignatius can’t help but dip into many areas of interest with little opportunity for plumbing the depths. It’s a smorgasbord, not a main course. Perhaps, others can zoom in into the areas he has explored.

Just as you won’t like everything on the smorgasbord, you won’t agree with everything he says and opines. But he sure does make you think and shakes you to your roots. Could that be, you ask and sometimes wonder, and concede, yes, it could be.

It’s a book written by a Malaysian for Malaysians, and to some extent, you need to be a Malaysian to understand the full import of the book and its nuances, but someone not attuned to local politics will nevertheless learn a lot more from it than many cool, detached, unimpassioned academic treatises.

It’s about heart and soul – all of ours and the nation’s – at the end of the day. Here, Ignatius does a fine job of his purpose in challenging Dr Mahathir’s demented vision for the nation, and to suggest that it is both inconsistent with the Merdeka compact and utterly ruinous of our future.

Read it for yourself! I highly recommend that you do. – The Vibes, September 23, 2021

Paradise Lost retails at RM60 per copy. Orders can be made through this website

P. Gunasegaram is chief executive of research and advocacy group Sekhar Institute and senior editorial consultant of PETRA News

He discusses the concept of Bangsa Malaysia and Dr Mahathir’s convoluted reasons for why it was not achieved, the unsubstantiated narrative about the unpatriotic non-Malay and the increasing racial schism within a once multiracial civil service, which accelerated during Dr Mahathir’s time.

The rewriting of history to lessen the influence of those other than Malays in the history of Malaysia is another sore point. Ignatius delves into history to point out the contributions of figures besides those usually named to the development of Malaysia in his chapter, reclaiming history.

One of the key features of Malaysia is its undue Islamisation, with political leaders, including Dr Mahathir, claiming that Malaysia is an Islamic state, and even an Islamic fundamentalist state. He traces it to the Saudis for building up a cadre of Wahhabi-trained academics, preachers and teachers, now agitating for greater Islamisation.

Inevitably, the discussion moved on to an Islamic state and hudud law, but not before delving into some interesting details on how PAS president Datuk Seri Abdul Hadi Awang once praised DAP for standing with PAS when the Kelantan government fell to Barisan Nasional in 1978. His stance changed later.

It should be obvious that Hadi’s Islamic state is the complete antithesis of the democratic, secular and inclusive character of our constitution, and for that reason alone must be taken seriously…. He is by far the most bigoted and extremist politician in the country, the greatest danger to our way of life and indeed to our very existence as a secular constitutional democracy.”

The last section of the book deals with reform, or the lack of it, under Dr Mahathir’s prime ministership round two. Even here, as Ignatius points out with example after example, the issue of race and religion was used and whipped up again and again to prevent many key reforms. The term “deep state” comes up as an obstacle to reform.

He traces the economic origins of Malay hegemony and writes: “In any case, the NEP (New Economic Policy) was never purely about the eradication of poverty irrespective of race or forging national unity; it hid a more crucial and overarching political objective – ensuring Malay hegemony.”

How true! And because it was true, the enormous opportunities it created gave rise to corruption on a grand scale, leading to the largest theft in the world via 1Malaysia Development Bhd.

For all that talk of doom and gloom, Ignatius ends on a hopeful note. He quotes Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra al-Haj first: “We must be brave, we must be fair and we must be just, so that come what may, we shall be ready as united Malaysian people to meet it.”

And then he says: “Let us, therefore, not grow weary of fighting for what is good and just, for in due season we will reap, if we do not give up.”

It’s a broad canvas that Ignatius paints, and an ambitious undertaking. Perhaps, one of the book’s weaknesses is that the sweep is a panorama too wide, with details getting lost in the size. Ignatius can’t help but dip into many areas of interest with little opportunity for plumbing the depths. It’s a smorgasbord, not a main course. Perhaps, others can zoom in into the areas he has explored.

Just as you won’t like everything on the smorgasbord, you won’t agree with everything he says and opines. But he sure does make you think and shakes you to your roots. Could that be, you ask and sometimes wonder, and concede, yes, it could be.

It’s a book written by a Malaysian for Malaysians, and to some extent, you need to be a Malaysian to understand the full import of the book and its nuances, but someone not attuned to local politics will nevertheless learn a lot more from it than many cool, detached, unimpassioned academic treatises.

It’s about heart and soul – all of ours and the nation’s – at the end of the day. Here, Ignatius does a fine job of his purpose in challenging Dr Mahathir’s demented vision for the nation, and to suggest that it is both inconsistent with the Merdeka compact and utterly ruinous of our future.

Read it for yourself! I highly recommend that you do. – The Vibes, September 23, 2021

Paradise Lost retails at RM60 per copy. Orders can be made through this website

P. Gunasegaram is chief executive of research and advocacy group Sekhar Institute and senior editorial consultant of PETRA News

Books have been written about Jibby and 1MDB too but KT had no interest blogging about them.

ReplyDeleteBut books on Toonsie.....KT has infinite interest....must be visceral hatred for Toonsie....ha ha ha....

Nah....The Three Books on 1MDB, with review some more....ha ha ha....

ReplyDeleteHow Did the 3 Books On 1MDB Stack Up Against Each Other? We Tell You..

https://www.unreservedmedia.com/1mdb-books-sarawak-report-billion-dollar-whale/