A Merdeka introspective on a needless death – P. Gunasegaram

Where did a man’s hatred for an old security guard come from?

Independence means different things to different people, depending on which social stratum they come from and where they are now. – AFP pic, September 2, 2021

ON the eve of Merdeka Day, August 31, I watched a rather disturbing video of an old security guard being viciously attacked physically and repeatedly, without any provocation, in front of a toddler.

It turns out the attacker was a fairly high-ranking member of Bersatu, a Malay-only party, set up just before the elections of 2018. The aged security guard, who was Indian, had at an Ipoh condominium apparently told the attacker that the swimming pool was closed and therefore his son could not use it.

For just following instructions from his employer, the security guard sustained serious injuries and was hospitalised for several months before he died of a lung infection. His family maintained that his injuries were the source of his death.

Authorities are investigating the death, now classifying the incident as murder instead of the earlier charge of causing grievous hurt after the assault last December. I hope they get him and punish him under the law for an unwarranted deadly attack on a defenceless man for merely doing his job.

But I wonder what it was that led this attacker to have so much hatred for this old security guard. Where did it emanate from? And did he have any thought at all for the welfare of this other person, a fellow citizen?

Did he think of him as a lesser person, as a person who was responsible for his own troubles? Did the attack take place for racial reasons? What did independence mean for the old man...and for the one who attacked him without mercy?

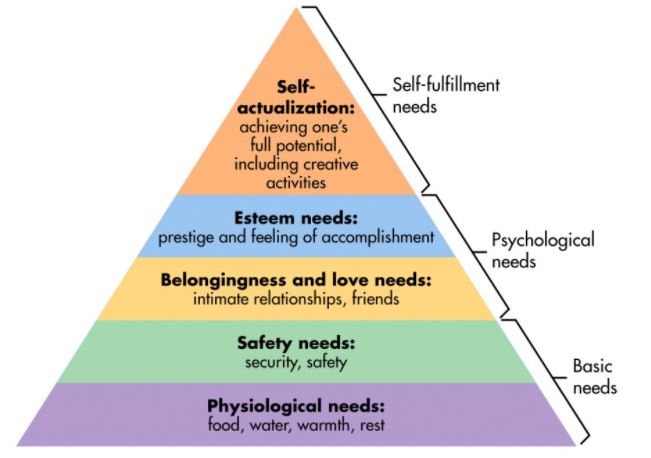

Independence means different things to different people, depending on what social strata they come from and where they are now. At the most basic level, it means not just freedom from hunger but access to good food, and a good standard of living exemplified by proper, decent accommodation and enough money for leisure.

These are illustrated in Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs.

It is a rather telling tragedy that after 64 years of independence, from a good start where we had among the highest living standards in Asia, that we are still pretty much stuck in the area of basic needs for a significant part of the population. We have not even succeeded in providing the most basic needs for all.

In a country like ours, which potentially has enough for everyone, there are still many who lack food, have poor housing, and earn salaries too low to provide for an adequate standard of living.

For these, the promise of independence and a better life means little when even these cannot be met. Safety needs are not adequately met either, and the security of many cannot be sufficiently protected after all these years, even worsening in some cases. The competence and independence of enforcement agencies are in question.

What went wrong?

This can be traced to a steady deterioration of the quality of government after the ruling government received a rude setback in the 1969 general elections, following which there were engineered racial riots and harsh new laws and enforcement.

The aim was to perpetuate the power of the ruling party, which was then the Alliance Party, an Umno-dominated coalition that included MCA and MIC. Thus the New Economic Policy (NEP) was implemented in the 1970s to eradicate poverty irrespective of race and to eliminate the identification of race with occupation.

But it was rapidly perverted into what basically became a scheme to transfer assets cheaply to well-off Malays and to provide advantages in terms of equity ownership rather than building expertise. These privileges became difficult to roll back, not because they benefited the poor Bumiputeras but because it became a tool of super-enrichment of the well-off Bumiputera political class without their corresponding effort.

Thus we had a new rich Bumiputera class of businessmen – the Umnoputeras – who were often also politicians who became fabulously rich because of the NEP. And when this was pointed out, they spoke in militant and threatening terms of how the non-Bumiputeras were a threat to them.

Social restructuring met some initial success through organisations such as Permodalan Nasional Bhd and Petronas, which managed to build a Bumiputera management class that otherwise would not have been built.

But after Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad came into power in 1981, there was an acceleration of projects that were given to select people, all of which required Bumiputera participation at very favourable rates through privatisation.

Thus we had a slew of independent power producers, toll road projects, water and sewage privatisations, etc, that spent billions of money. Projects and contracts were given to connected people, both Bumiputeras and non-Bumiputera, provided a part of ownership was allocated at concessional rates to Bumiputera interests – specially connected, of course.

While the number of rich in Malaysia burgeoned, there was a widening in the gap between the rich and the poor. Cheap, often illegal labour, imported from countries such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, India, and Myanmar fattened private sector coffers and made Malaysia internationally competitive but depressed local wages, exacerbating income gaps.

These policies have to be fuelled by the support of the masses – the Bumiputera masses – for political support. Thus there was brainwashing through agencies such as Biro Tatanegara or BTN, the national civics bureau, where according to many accounts, Malay government servants were brainwashed into believing that their problems were caused by the non-Bumiputeras.

Cheap, often illegal labour, imported from countries such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, India, and Myanmar has fattened private sector coffers and made Malaysia internationally competitive but depressed local wages, exacerbating income gaps. – Pixabay pic, September 2, 2021

This made worse a situation that was already bad because of religious animosity between Muslims and non-Muslims, with extreme policies favoured by some sections in the Malay community who viewed other religions as a threat to Islam.

The net result was government-sanctioned resentment between the Bumiputeras and non-Bumiputeras. The Bumiputeras were made to think that their economic backwardness was because of non-Bumiputeras who took away their incomes and opportunities.

The non-Bumiputeras felt that Bumiputeras were given an unfair advantage when that advantage was only enjoyed by a small group of Bumiputeras, with a large portion of them not enjoying these benefits at all.

This made worse a situation that was already bad because of religious animosity between Muslims and non-Muslims, with extreme policies favoured by some sections in the Malay community who viewed other religions as a threat to Islam.

The net result was government-sanctioned resentment between the Bumiputeras and non-Bumiputeras. The Bumiputeras were made to think that their economic backwardness was because of non-Bumiputeras who took away their incomes and opportunities.

The non-Bumiputeras felt that Bumiputeras were given an unfair advantage when that advantage was only enjoyed by a small group of Bumiputeras, with a large portion of them not enjoying these benefits at all.

It is this tension and the systematic feeding of hatred to Bumiputeras against non-Bumiputeras that probably caused that unwarranted rage against a helpless old man doing his job by a much younger man who had far greater strength than him. And, perhaps, the thought that he could get away with it.

For the old security guard, independence, citizenship, and rights did not protect him against a deadly attack on him by a fellow citizen, a prominent member of a political party to boot, who probably thought him a lesser person.

If this government and the successive governments before them had done their job properly, racial income gaps could have been narrowed, and more importantly, all Malaysians would have attained a sufficient standard of living that guarantees equal opportunities for all.

Equal opportunity based on redressing economic imbalances and giving everybody the same chance to succeed is what we should always be aiming for, not systematically deepening and widening the rift between us to stay in power. There would be no need to fuel racial hatred.

There is only one way to prosper together, that is for all of us to have a good standard of living, equal opportunities for education and advancement, and to recognise that all of us have an equally rightful stake in the country. That’s what Tunku Abdul Rahman recognised long ago. But we lost our grasp on something we could have achieved.

We thought we had it in our hands again after GE14 in May 2018, but it slipped away because one person did not want it. Let’s not give up hope. Sometimes we have to regain independence after having gained it before and then lost it. Sometimes it is an ongoing process. We have to come back and gain ground after having lost it.

The important thing is we – all of us – keep trying. – The Vibes, September 2, 2021

P. Gunasegaram says if we want a better government, we need to do something about it. He is chief executive of research and advocacy unit Sekhar Institute and editorial consultant of The Vibes

Did Mahathir have a hand in killing the security guard ?

ReplyDeleteIf the writer thinks that the self entitled expectations of the Ketuanans will go away, he has to have his head examined.

ReplyDeleteThis is too entrenched and I personally gave up long ago. It is why I work not in Malaysia.

The perpetrator definitely is not concerned about any potential blow back because he belongs to the ketuanan class.

I doubt if he gave a f**k about the poor security guard when he went on the rampage.

What we should be concerned about now is what will the police do. And importantly, what will the Kerajaan Allah do and also what the useless Idrus Harun will do.

P Guna loves to link everything to his hatred for UMNO and BN.

ReplyDeleteIt's simple: man beat up security guard. He should be charged in court. What is the link to UMNO etc.? In the US probably if this happened and it was a white man beating a black man the white man would have gone free.