Malaysiakini:

The turning of the tide in Tanjong Piai

by BRIDGET WELSH

COMMENT | The voters in Tanjong Piai delivered the worst loss for an incumbent government in a federal by-election in Malaysian history this weekend.

It was also another first: this was the highest level of swing against Dr Mahathir Mohamad in his two tenures as prime minister in any election (including the reformasi swing of 1999).

Across races, generations and genders, voters not only protested, they also sent a clarion call that Mahathir, his party and his coalition partners in government are failing New Malaysia. Fittingly in this constituency by the water, the political tide turned.

This analysis based on statistical estimates of the polling station results show that Pakatan Harapan lost the most ground among the key supporters it won in GE14, notably Chinese, older, and women voters. The loss among young voters, another key gain in GE14, was not as large as others, but sizeable.

The discussion that follows lays out changes in turnout and support and discusses the implications of the findings in this by-election. Harapan needs to learn the lessons from this result if (and this is a big if) it is able to turn the tide in its favour. This will mean addressing head-on the difficult questions of reform, its approach to governance and ultimately, succession.

Turnout variation

The result against Harapan in favour of BN is stark, with swings well beyond those projected earlier in various scenarios. They begin with who came out to vote - the turnout.

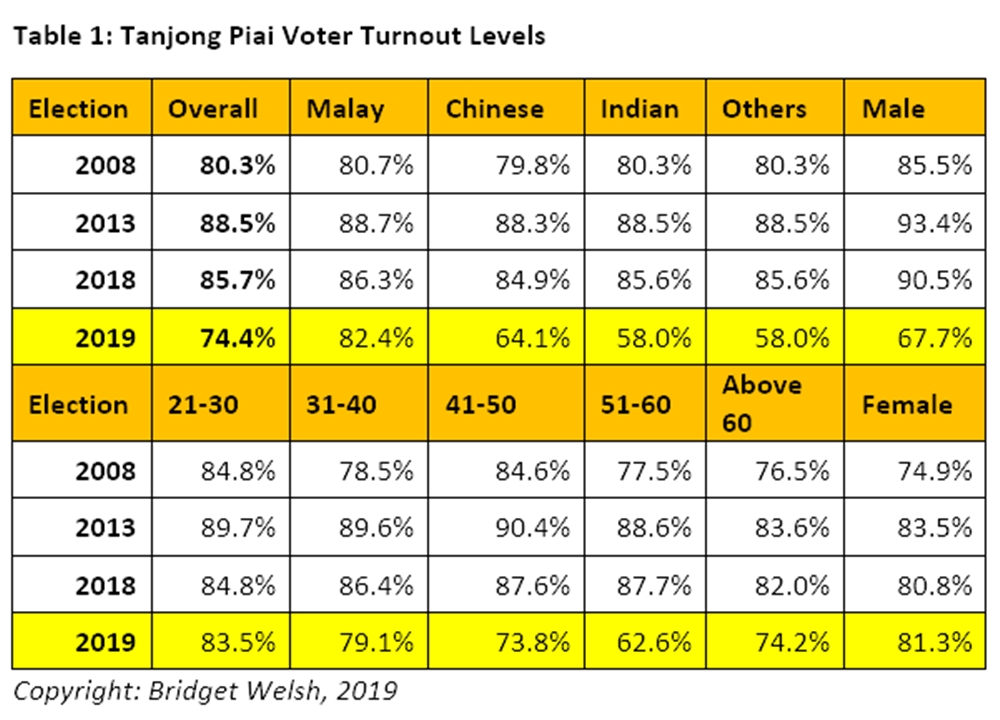

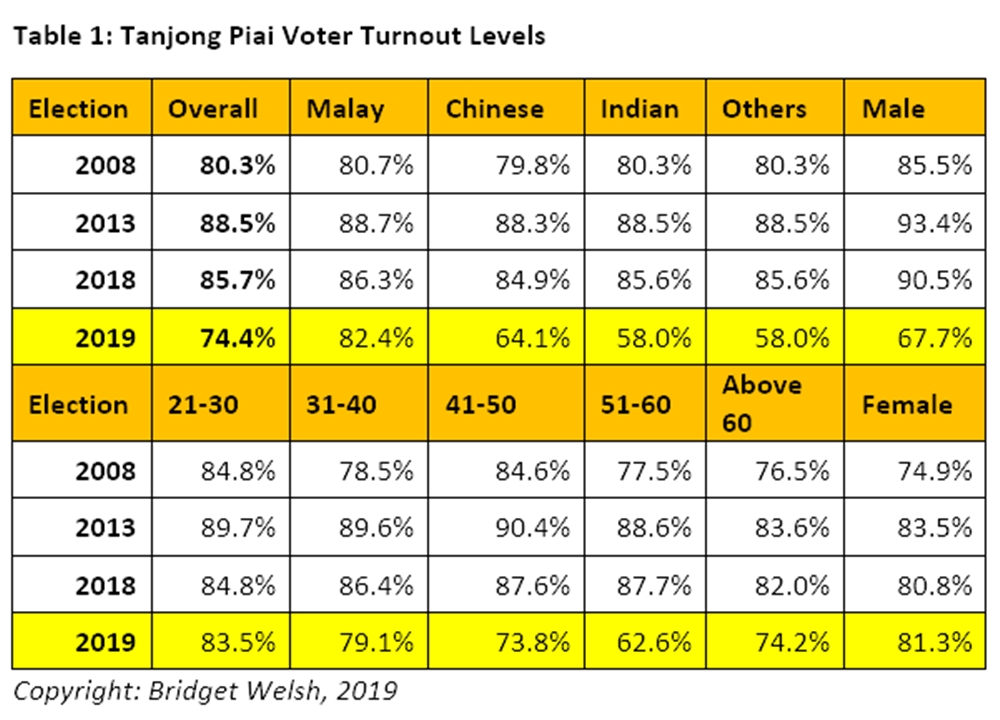

First of all, there was a considerable drop in the overall turnout from 85.7% in GE14 to 74.4%. This level of over 10% in a by-election is not unusual, but the composition of the decline in turnout is interesting.

Across ethnic groups, the largest drops in turnout were among Chinese voters (an estimated 20.8%) and the other communities, Indians and other ethnic groups (an estimated 27.6%, who make up a small number of the actual voters but opted not to vote). The decline in turnout among Malays was nominal, at an estimated 3.8%. Malay political parties were able to mobilise voters more effectively to come to the polls. Chinese and other non-Malay voters opted to stay at home as part of their protest.

The generational and gender dimensions of turnout levels are also noteworthy. The greatest decline in turnout was among older voters, above 50, with those from 51-60 years recording an estimated 25.2% drop in turnout, and above 60 years, an estimated 7.8% drop in turnout. Younger voters participated in this election, with considerably lower declines in turnout compared to other age cohorts. This differs from other by-elections as usually younger voters who are mostly outstation don’t come home to vote.

This finding points to two overall issues – the core of Mahathir’s generation support – above 60 – did not come out to the same degree for him. Second, national findings in GE14 show that those between 51-60 years were socialised during the reformasi years and disproportionately support the opposition, the then Barisan Alternatif and later Pakatan Rakyat/Harapan, were not willing to go to the voting booth for Bersatu. Many of these voters who support reform opted not to vote by a considerable margin.

The third pattern in the turnout results involves gender. Men stayed at home with a drop in turnout of an estimated 22.8%, while women voted with a drop of less than an estimated 1%. This made a difference in the results as women came out and, as will be shown below, changed their allegiance. The Tanjong Piai defeat was not just along ethnic lines, but gender lines as well.

The turnout results suggest two broad trends – the declining salience of ‘Mahathir’ (and his party) as a pull in the election and deep alienation not just among Chinese but many of those who identified with reform and have found the current administration lacking in this regard.

Changes in political allegiances

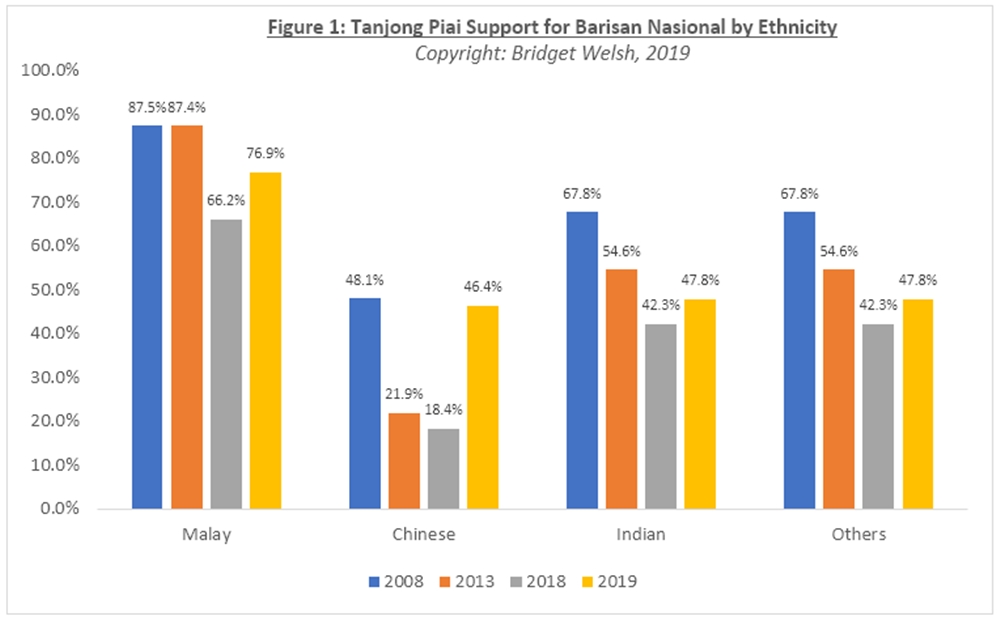

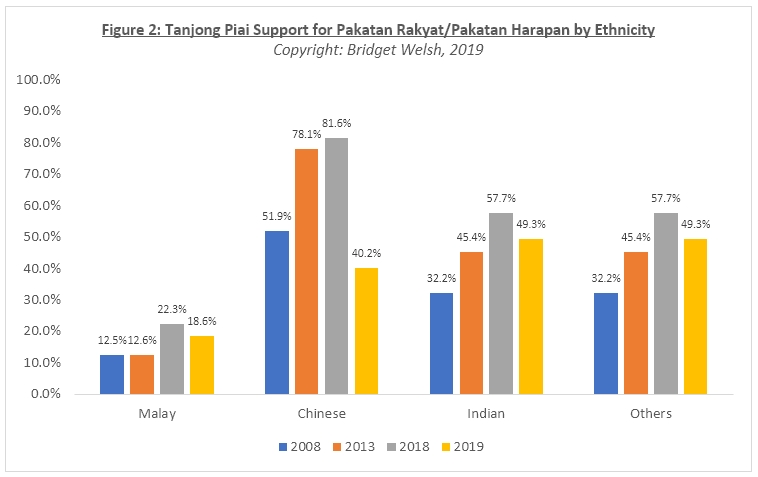

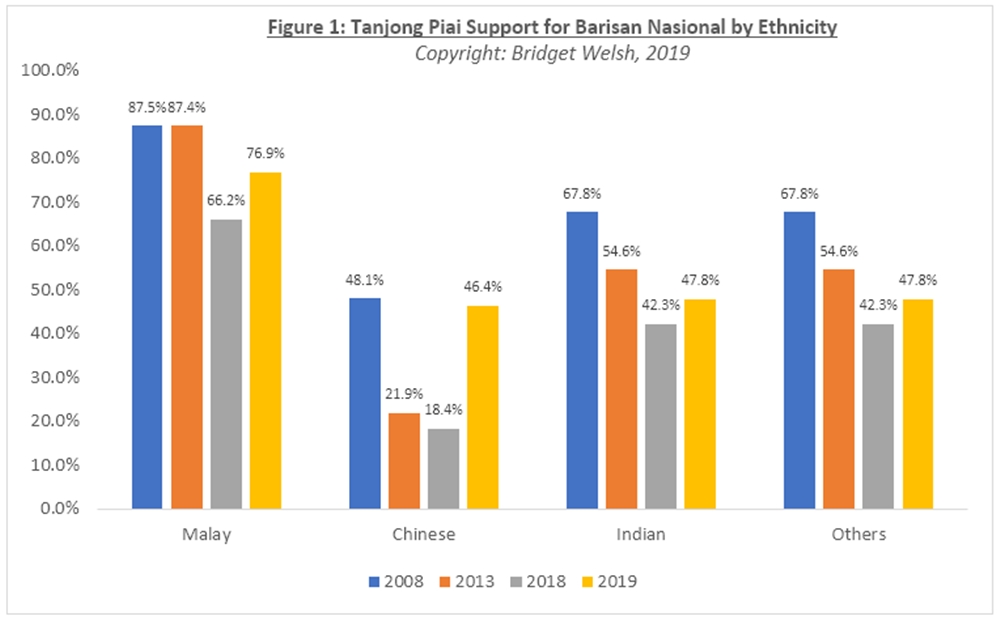

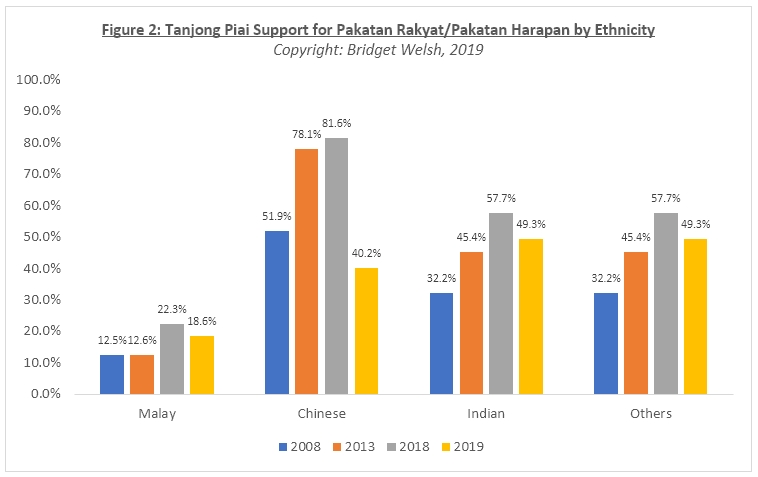

These broad shifts are evident in the support levels for the different parties as well. Looking at the estimated voting along ethnic lines detailed in the two figures below, the results show that Harapan’s defeat was across races.

The biggest swing was among Chinese voters, as the MCA candidate captured 46.4% of these votes (not the majority, but the largest plurality). This was an estimated gain of 28% among Chinese Tanjong Piai voters, which essentially returns the party to its 2008 levels of support. For Harapan, which also experienced a loss of support to Gerakan, the Chinese defection was a devastating shift of over half of previous support levels, a drop of 41.3%.

This speaks not only to the failings of Mahathir’s leadership in his constant racialised discourse and disrespect of this minority but anger at the DAP and mobilisation weaknesses of Johor DAP. The results show that the DAP has been seriously delegitimised among its traditional voters due to accommodation and its own failings in engaging its traditional political base.

The estimated changes among Malay voters show two important findings.

First, the estimated Malay support for Harapan did not change significantly, from 22.3% to 18.6%. Second, BN, however, did pick up support among Malays, an estimated 10.7%. This suggests that the bulk of voters that supported PAS, supported BN in this by-election. But BN support among Malays, however, is not in line with levels of earlier years in Johor, even with many of the PAS supporters behind them.

While the other communities (apart from the Chinese and Malays) make up a small share of the voters, the shift was across all the communities is in favour of BN and away from Harapan.

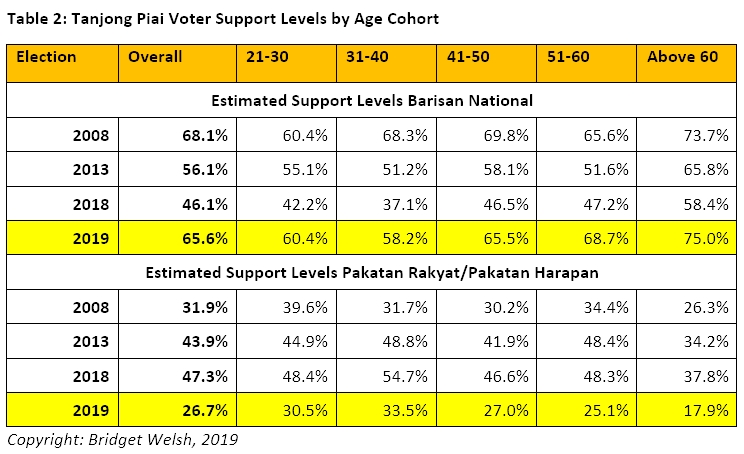

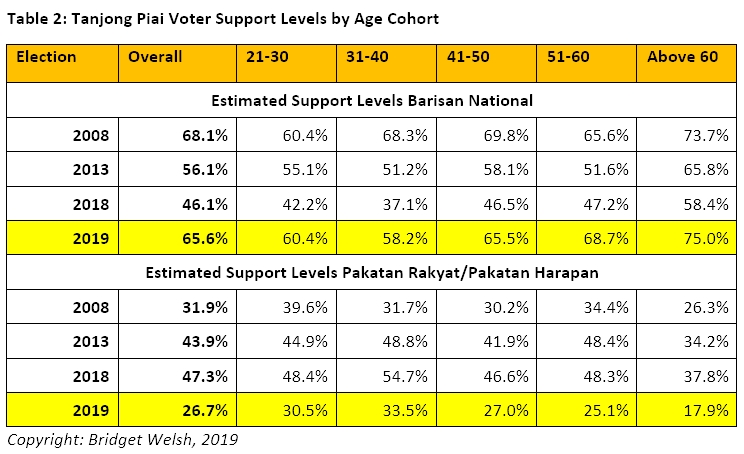

The generational estimates findings show a similar across-the-board swing, as outlined in Table 2 below. Voters between the ages of 51-60 years, the same ones who were estimated not to vote in the largest numbers, also recorded the highest estimated swing against Harapan, 23.2%.

This reinforces the point above, that the reformasi generation showed disappointment with Harapan. Mahathir also lost among those who voted for him in GE14, above 60 years old, in the range of an estimated 19.9%. BN exceeded its support levels among these cohorts compared to the recent past.

Young voters also punished Harapan, but it was those between 31-40 where this was most concentrated - with 21.3% drop in support for Harapan. While BN made up ground among the youth, it has not regained its support levels of the past among younger voters.

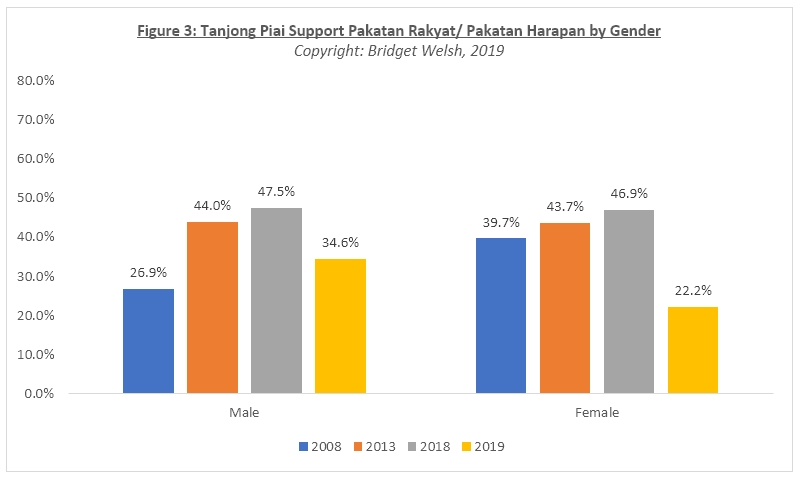

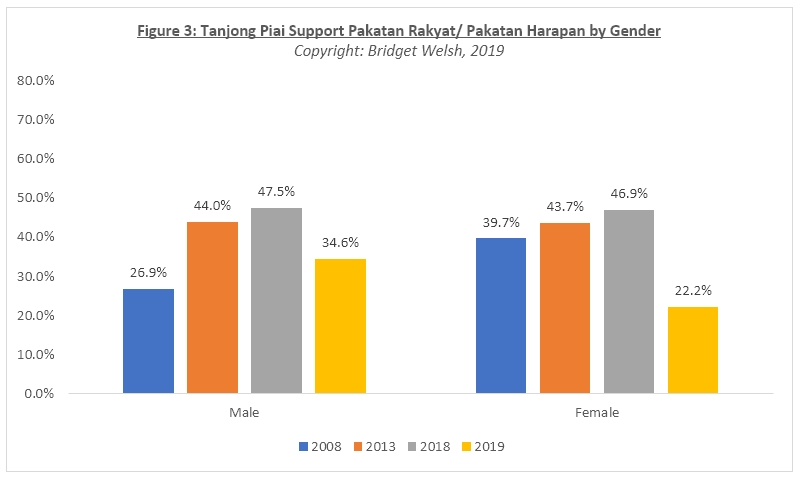

The gender findings are especially interesting. The analysis shows that both men and women voted for BN in greater numbers, gains of 16.1% and 20.3% respectively, but the most striking change was the significant drop in support of women for Harapan, as shown in Figure 3. Like Chinese support, support by women for Harapan dropped by half, from an estimated 46.9% to an estimated 22.2% - an estimated 24.7% drop (a small share of this difference went to Gerakan’s female candidate).

Harapan has worked to engage on gender issues in this year’s Budget, but it clearly has lost ground among women in Tanjong Piai. They voted in higher numbers and switched their vote away from Harapan.

Issues such as Harapan state cabinet member Paul Yong charged with rape in Perak being allowed to go back to work the day before the polls should not be ignored as a contributing factor to the female protest vote. The court process should be completed before a man accused of gender violence should be allowed to work on behalf of the electorate in a senior position.

The other issue this gender swing shows is the lack of connectivity of Harapan parties among women, a traditional strength of BN, especially Umno.

Turning (in)to BN

The shifts in Tanjong Piai went beyond race, to extend along other social cleavages as well. They do not, however, fully offer an understanding of the drivers of change. Here, there has been already a series of interpretations – from Mahathir’s leadership failings, claims of internal sabotage within Harapan to the pull of the BN. As in the results themselves, there are multiple factors that caused this loss for Harapan.

This analysis of the results points to three significant factors:

1) Exclusion of concerns of the non-Malay (previous) base by the Mahathir government. Ironically, all the racialised Malay-oriented courting by Mahathir/Bersatu not only lost it support among Malays, it decimated the support among its core supporters, non-Malays.

2) Harapan has failed to satisfy those who voted for it for change. The lame excuses (and acceptance) and outright measures that echo practices of the past (patronage, racial discourse, persistent abuse of authority through arrests and inadequate change in the key sectors of education and the economy) did not resonate among those wanting a ‘New Malaysia’. Harapan calls to reject ‘racist’ policies were just not credible.

3) Worse yet, the leaders were acting as if they were entitled to a victory for doing what they were put into office to do – address the abuses of the past and move Malaysia forward. The hubris and arrogance shown during Harapan’s Tanjong Piai campaign, which followed old narratives and practices (which mistakenly predicted victory), worsened the result. Harapan has lost its connectivity with the electorate, reflecting the weakness of these parties on the ground as well as failings in communication. Most important of all, Tanjong Piai voters showed that if parties act like BN, they might as well vote for BN.

The Tanjong Piai result brings to the fore the question of Mahathir’s leadership. In Tanjong Piai, he failed the test – badly.

Mahathir has yet to properly appreciate that Malaysia is not the place it was when he was first in office. Divisive policies and approaches to politics that echo the past just do not win support. The negativity of Mahathir’s leadership (against his own partners, through the use of race and persistent use of attacks) does not resonate with the electorate that voted for a positive future.

Harapan and Mahathir have to seriously reform their approaches to voters and among themselves. Self-destructive politics is counter-productive. The Tanjung Piai voters did Harapan and Mahathir a favour in sending this strong signal, as it shows clearly a pressing need to turn the tide.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She recently became an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (UNARI) based in Kuala Lumpur

It was also another first: this was the highest level of swing against Dr Mahathir Mohamad in his two tenures as prime minister in any election (including the reformasi swing of 1999).

Across races, generations and genders, voters not only protested, they also sent a clarion call that Mahathir, his party and his coalition partners in government are failing New Malaysia. Fittingly in this constituency by the water, the political tide turned.

This analysis based on statistical estimates of the polling station results show that Pakatan Harapan lost the most ground among the key supporters it won in GE14, notably Chinese, older, and women voters. The loss among young voters, another key gain in GE14, was not as large as others, but sizeable.

The discussion that follows lays out changes in turnout and support and discusses the implications of the findings in this by-election. Harapan needs to learn the lessons from this result if (and this is a big if) it is able to turn the tide in its favour. This will mean addressing head-on the difficult questions of reform, its approach to governance and ultimately, succession.

Turnout variation

The result against Harapan in favour of BN is stark, with swings well beyond those projected earlier in various scenarios. They begin with who came out to vote - the turnout.

First of all, there was a considerable drop in the overall turnout from 85.7% in GE14 to 74.4%. This level of over 10% in a by-election is not unusual, but the composition of the decline in turnout is interesting.

Across ethnic groups, the largest drops in turnout were among Chinese voters (an estimated 20.8%) and the other communities, Indians and other ethnic groups (an estimated 27.6%, who make up a small number of the actual voters but opted not to vote). The decline in turnout among Malays was nominal, at an estimated 3.8%. Malay political parties were able to mobilise voters more effectively to come to the polls. Chinese and other non-Malay voters opted to stay at home as part of their protest.

The generational and gender dimensions of turnout levels are also noteworthy. The greatest decline in turnout was among older voters, above 50, with those from 51-60 years recording an estimated 25.2% drop in turnout, and above 60 years, an estimated 7.8% drop in turnout. Younger voters participated in this election, with considerably lower declines in turnout compared to other age cohorts. This differs from other by-elections as usually younger voters who are mostly outstation don’t come home to vote.

This finding points to two overall issues – the core of Mahathir’s generation support – above 60 – did not come out to the same degree for him. Second, national findings in GE14 show that those between 51-60 years were socialised during the reformasi years and disproportionately support the opposition, the then Barisan Alternatif and later Pakatan Rakyat/Harapan, were not willing to go to the voting booth for Bersatu. Many of these voters who support reform opted not to vote by a considerable margin.

The third pattern in the turnout results involves gender. Men stayed at home with a drop in turnout of an estimated 22.8%, while women voted with a drop of less than an estimated 1%. This made a difference in the results as women came out and, as will be shown below, changed their allegiance. The Tanjong Piai defeat was not just along ethnic lines, but gender lines as well.

The turnout results suggest two broad trends – the declining salience of ‘Mahathir’ (and his party) as a pull in the election and deep alienation not just among Chinese but many of those who identified with reform and have found the current administration lacking in this regard.

Changes in political allegiances

These broad shifts are evident in the support levels for the different parties as well. Looking at the estimated voting along ethnic lines detailed in the two figures below, the results show that Harapan’s defeat was across races.

The biggest swing was among Chinese voters, as the MCA candidate captured 46.4% of these votes (not the majority, but the largest plurality). This was an estimated gain of 28% among Chinese Tanjong Piai voters, which essentially returns the party to its 2008 levels of support. For Harapan, which also experienced a loss of support to Gerakan, the Chinese defection was a devastating shift of over half of previous support levels, a drop of 41.3%.

This speaks not only to the failings of Mahathir’s leadership in his constant racialised discourse and disrespect of this minority but anger at the DAP and mobilisation weaknesses of Johor DAP. The results show that the DAP has been seriously delegitimised among its traditional voters due to accommodation and its own failings in engaging its traditional political base.

The estimated changes among Malay voters show two important findings.

First, the estimated Malay support for Harapan did not change significantly, from 22.3% to 18.6%. Second, BN, however, did pick up support among Malays, an estimated 10.7%. This suggests that the bulk of voters that supported PAS, supported BN in this by-election. But BN support among Malays, however, is not in line with levels of earlier years in Johor, even with many of the PAS supporters behind them.

While the other communities (apart from the Chinese and Malays) make up a small share of the voters, the shift was across all the communities is in favour of BN and away from Harapan.

The generational estimates findings show a similar across-the-board swing, as outlined in Table 2 below. Voters between the ages of 51-60 years, the same ones who were estimated not to vote in the largest numbers, also recorded the highest estimated swing against Harapan, 23.2%.

This reinforces the point above, that the reformasi generation showed disappointment with Harapan. Mahathir also lost among those who voted for him in GE14, above 60 years old, in the range of an estimated 19.9%. BN exceeded its support levels among these cohorts compared to the recent past.

Young voters also punished Harapan, but it was those between 31-40 where this was most concentrated - with 21.3% drop in support for Harapan. While BN made up ground among the youth, it has not regained its support levels of the past among younger voters.

The gender findings are especially interesting. The analysis shows that both men and women voted for BN in greater numbers, gains of 16.1% and 20.3% respectively, but the most striking change was the significant drop in support of women for Harapan, as shown in Figure 3. Like Chinese support, support by women for Harapan dropped by half, from an estimated 46.9% to an estimated 22.2% - an estimated 24.7% drop (a small share of this difference went to Gerakan’s female candidate).

Harapan has worked to engage on gender issues in this year’s Budget, but it clearly has lost ground among women in Tanjong Piai. They voted in higher numbers and switched their vote away from Harapan.

Issues such as Harapan state cabinet member Paul Yong charged with rape in Perak being allowed to go back to work the day before the polls should not be ignored as a contributing factor to the female protest vote. The court process should be completed before a man accused of gender violence should be allowed to work on behalf of the electorate in a senior position.

The other issue this gender swing shows is the lack of connectivity of Harapan parties among women, a traditional strength of BN, especially Umno.

Turning (in)to BN

The shifts in Tanjong Piai went beyond race, to extend along other social cleavages as well. They do not, however, fully offer an understanding of the drivers of change. Here, there has been already a series of interpretations – from Mahathir’s leadership failings, claims of internal sabotage within Harapan to the pull of the BN. As in the results themselves, there are multiple factors that caused this loss for Harapan.

This analysis of the results points to three significant factors:

1) Exclusion of concerns of the non-Malay (previous) base by the Mahathir government. Ironically, all the racialised Malay-oriented courting by Mahathir/Bersatu not only lost it support among Malays, it decimated the support among its core supporters, non-Malays.

2) Harapan has failed to satisfy those who voted for it for change. The lame excuses (and acceptance) and outright measures that echo practices of the past (patronage, racial discourse, persistent abuse of authority through arrests and inadequate change in the key sectors of education and the economy) did not resonate among those wanting a ‘New Malaysia’. Harapan calls to reject ‘racist’ policies were just not credible.

3) Worse yet, the leaders were acting as if they were entitled to a victory for doing what they were put into office to do – address the abuses of the past and move Malaysia forward. The hubris and arrogance shown during Harapan’s Tanjong Piai campaign, which followed old narratives and practices (which mistakenly predicted victory), worsened the result. Harapan has lost its connectivity with the electorate, reflecting the weakness of these parties on the ground as well as failings in communication. Most important of all, Tanjong Piai voters showed that if parties act like BN, they might as well vote for BN.

The Tanjong Piai result brings to the fore the question of Mahathir’s leadership. In Tanjong Piai, he failed the test – badly.

Mahathir has yet to properly appreciate that Malaysia is not the place it was when he was first in office. Divisive policies and approaches to politics that echo the past just do not win support. The negativity of Mahathir’s leadership (against his own partners, through the use of race and persistent use of attacks) does not resonate with the electorate that voted for a positive future.

Harapan and Mahathir have to seriously reform their approaches to voters and among themselves. Self-destructive politics is counter-productive. The Tanjung Piai voters did Harapan and Mahathir a favour in sending this strong signal, as it shows clearly a pressing need to turn the tide.

BRIDGET WELSH is a Senior Research Associate at the Hu Feng Centre for East Asia Democratic Studies, a Senior Associate Fellow of The Habibie Centre, and a University Fellow of Charles Darwin University. She recently became an Honorary Research Associate of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia's Asia Research Institute (UNARI) based in Kuala Lumpur

If Toonsie could not fix the country in 22 years when he had 2/3rds parliamentary majority; he sure as hell can't fix it in 2 with only 6% of parliament seats.

ReplyDeleteHarapan Presidential Council must demand he step down, immediately.

Bersatu won only 12 seats in elections but hold 6 Ministerial positions, including PM. Ridiculous.

In hindsight, how do we Malaysians expect a leopard to change its spots?

ReplyDeleteIndeed those ketuanan freaks & zombies CAN never change their spots!

DeleteA bird in hand is worth more than 2 in the bush.

ReplyDeleteMahathir went after the 2 birds in the bush, and not only failed to catch any of the 2 birds in the bush, he let go the bird in hand....

End up nothing.